WesDivest’s Intersectional Divestment Campaign Sparks Controversy in Wesleyan’s Climate Action Circles

When WesDivest member Leah Levin Pensler ’20 spoke at the Climate Strike on Sept. 20, she called on the University to divest its endowment from the fossil fuel industry. Then, she made another, more controversial demand.

“Not only must this discussion address how the University contributes to driving society towards climate catastrophe, but we must openly condemn the University’s financial role in atrocities occurring around the globe, namely the University’s holdings in Israeli apartheid, and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians,” she said. “It is time for Wesleyan to divest from both the fossil fuel industry and companies entangled in the Israeli occupation of Palestine.”

With this charge, an unofficial platform shift began to take hold in WesDivest. Instead of just advocating for the University to divest from the fossil fuel industry, WesDivest would now stand for divestment from Israel as well, assuming a more intersectional approach to their divestment campaign. The shift would ultimately prove divisive, balkanizing the group’s members into factions, with different visions for what the goals and tactics of the club should be. Many students at the rally were surprised at the mention of Israel in Pensler’s speech, as it seemed inconsistent with WesDivest’s recent efforts to rebrand as a climate advocacy group whose divestment goals focused solely on fossil fuels.

The previous iteration of WesDivest—whose legacy lives on in stickers across campus—had called on the University to divest not only from fossil fuels, but also from Israel and private prisons. But after a contentious 2015 sit-in in President Roth’s office, the group, which had not yet achieved its desired goals, fizzled out.

When WesDivest was revived last fall, the new members of the club sought to establish something lasting and impactful, something that wouldn’t simply disintegrate as students cycle through the University.

“We were left trying to figure out why WesDivest had failed in the past and what we could do differently to ensure that didn’t happen again,” Bella Whiting ’21, a key organizer of last year’s WesDivest revival, explained in a message to The Argus. “Very quickly, we decided to narrow the lease to focus solely on divestment from fossil fuels.”

This decision, they hoped, would increase their chances of success and allow them to gain broader support. Part of the reason that the last version failed, Whiting explained, was it didn’t have widespread support on campus, due in part to the breadth of its platform. But some were dismayed by the exclusion of Israel from the revised agenda.

“I was definitely frustrated with the sole focus on the fossil fuel industry, because I see climate change [activism] as a movement that really needs to address and encompass all political movements, and all social movements around the world, all struggles,” Pensler, who is also a member of Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), said.

Pensler knew that her comments might create tension. However, she, along with several other members of the club who had been meeting informally since the beginning of the semester, decided it was time to bring the issue to the forefront of the climate conversation. In the days before the strike, they composed a statement, which Pensler volunteered to read. Although Pensler did not give the speech as an official WesDivest representative, she was representing a certain faction of the club, and, surrounded by a group of students carrying divestment signs, the nature of her precise role bore little import.

“I can’t say I was surprised but I was upset that people who spoke about divestment and WesDivest went after Israel really hard, to put it bluntly,” Ben Silverstone ’22, a Climate Action Group (CAG) organizer, former WesDivest member, and Wesleyan Jewish Community (WJC) member, said. “And so I quit WesDivest because of that. Literally two hours after the strike, I quit WesDivest. It was just like, I could not be a part of that movement anymore, because they extended divestment to other things.”

“I could tell there was a contrast between what I was saying and I would say the atmosphere…and the demands,” Pensler said later.

The list of demands released by CAG—the club responsible for organizing the strike—included divestment from fossil fuels by 2032. This demand was viewed by some members of WesDivest as lenient and unradical. They had long been dissatisfied by the Wesleyan sustainability community’s sole focus on fossil fuel divestment, and wanted to use the climate strike as an opportunity to push the administration further.

“It was very clear there, at that event, that the University was taking advantage of it to co-opt it, and that was a sign to me and other students that the demands weren’t strong enough,” Pensler said. “[It was] too easy for the University to co-opt. That’s how we now we need to push harder. And that’s what other students, including myself, decided to do, together.”

Their decision to use the climate strike as a platform to push their agenda was concerning to some members of the Wesleyan sustainability community.

“I was honestly super surprised and a little sad to hear this,” Whiting, who is currently abroad, wrote. “It seemed as if the rally for divestment from Israeli occupation during the climate/ divestment seemed to detract from the key issues the event was structured around and created more of a divide than a union.”

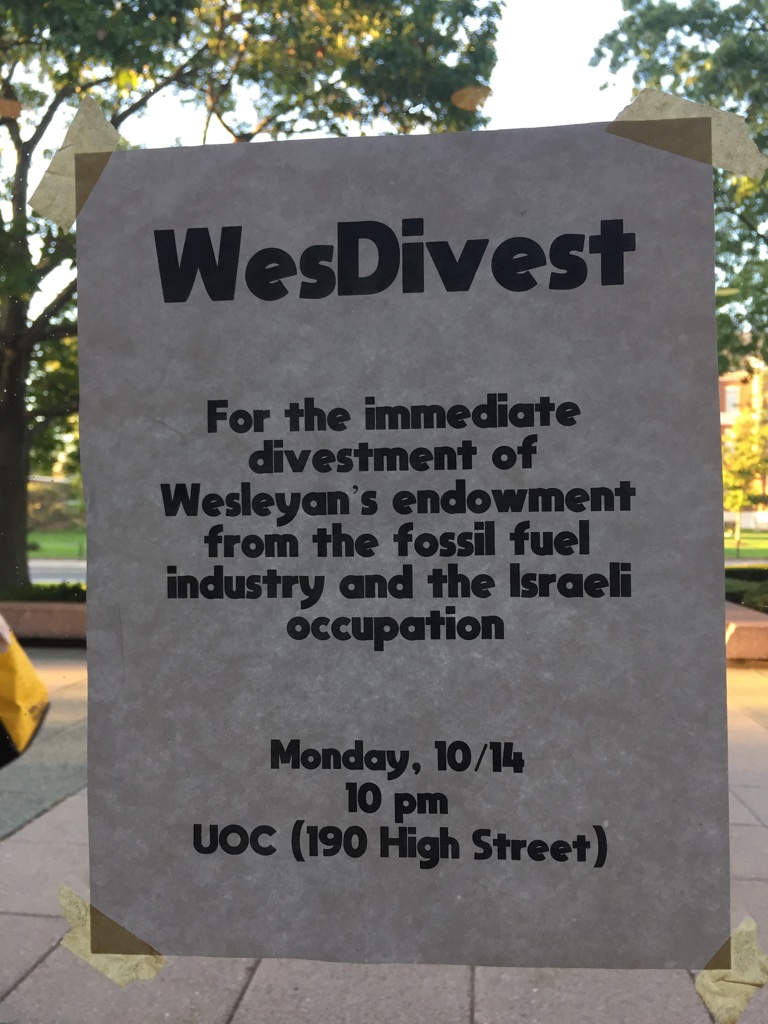

Following the climate strike, Pensler and the other new WesDivest organizers posted flyers around campus about an upcoming meeting in the University Organizing Center.

“WesDivest,” the flyers reads. “For the immediate divestment of Wesleyan’s endowment from the fossil fuel industry and the Israeli occupation.”

In the months that have passed since Pensler initiated the platform switch, divestment debates have been reinvigorated on campus, due in part to a series of events dedicated to the subject. WesDivest hosted a teach-in about the history of divest movements at the University; JVP hosted a discussion about why to include Israel in divestment movements; and, on the Friday before Thanksgiving, WesDivest joined a range of other clubs in protesting the board of trustees meeting. The intersectional nature of climate change as a social and political issue has become a central theme in these discussions and events, as students seek to understand how and why divestment from Israel and divestment from fossil fuels are connected to one another. The link, as some see it, is environmental racism and resource colonialism: The politics of resource distribution has played an important role the Israeli occupation.

“We were definitely trying to get people to rethink what climate justice means, and what it means to be at a climate strike and how this climate strike at Wesleyan connects to many other fights around the world,” Pensler said. “Obviously not everyone in the crowd agreed with what I read out loud.”

Indeed, some don’t see a strong connection between the two causes, as part of the reason WesDivest decided to narrow its focus was because members, at the time, felt that making an ideological link between fossil fuels and Israel would require them to include other social justice issues that also are loosely related.

“We felt that including divestment form the Israeli occupation was both too wide of a focus and a separate issue,” Whiting wrote. “Someone who believes in fossil fuel divestment doesn’t necessarily believe in divestment from the Israeli Occupation.”

The term “divestment” was popularized during South African anti-apartheid movements and was later co-opted by the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS) movement, an international Palestinian-led, anti-Zionist organization that advocates for institutions to withdraw support from Israel in all forms because of the ongoing human rights abuses that the state has committed against Palestinians. In recent years, BDS has also endorsed divestment from fossil fuels as a part of its platform.

“These divestment movements so quickly morph into one another, and especially with how valuable intersectionality is nowadays in social movements,” Silverstone said. “[But] I don’t believe it’s related.”

“The apartheid era is often brought up in that divestment was a tool that helped bring down the apartheid regime in South Africa,” Sustainability Director Jen Kleindienst said of the recent calls for divestment from Israel. “[But] the fossil fuel industry is more complicated than that, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is also more complicated than that, because it’s not bringing down a single system, it’s bringing down lots of interconnected systems.”

For Pensler, this inter-connectedness simply underscores the need for a broader, intersectional divestment campaign.

“And I don’t use that word [intersectional] lightly,” Pensler said. “I mean opposing all forms of racism, bigotry. Looking at fossil fuel industry, being critical of it. But also being critical of the U.S. government, being critical of the Wesleyan administration, being critical of Israeli authorities. These are all structures of power that we need to be critical of, and I see WesDivest now as taking that seriously.”

Kleindienst, however, emphasized what she sees as challenges of taking an intersectional approach to divestment advocacy.

“As time has gone on, it’s not really that hard for people to understand the intersectionality of an issue like climate change,” Kleindienst said. “The challenge when you start moving into investments is sort of… where do you stop, as far as what should we divest from…. There is a real challenge to figure out where to draw the borders of what is it okay to invest in and what is it not okay to invest in.”

In perpetuating the rhetoric of Israel as a colonial apartheid state, BDS has gained traction on campuses and in activist groups across the country. Silverstone characterized this language as anti-Semitic, echoing a common critique of BDS from critics across the political spectrum.

“I believe that the BDS movement, or movements that seek to portray Israel as a colonial apartheid state are rooted in anti-Semitism, because they delegitimize Jewish claims of indigeneity to Israel by calling it a colonial state, which is anti-Semitic,” Silverstone said. “So I support Palestinian liberation, I support ending the occupation, I am fairly liberal on Israel and I’m really happy that Bibi [Benjamin Netanyahu] is losing this election. But yeah, I don’t believe Israel is a colonial apartheid state, and I think portraying it as such is anti-Semitic.”

Pensler, however, believes that the conditions in Israel directly reflect the colonial nature of the Israeli government.

“We see apartheid there; we see the main authority that’s deemed legitimate being the Israeli authority,” she said. “We see a separation between Palestinians and Israelis, we see unequal treatment. So we see an apartheid state…. We can’t combat anti-Semitism without opposing the Israeli occupation. And it is an occupation, it is an apartheid state.”

Sasha Linden-Cohen can be reached at srcohen@wesleyan.edu.

Let’s support climate change, Israel divestment, and add single payer healthcare, and 4 day work week, and gun buy-backs and 50 more issues that suit the personal agendas of different students. This is chaos.

Watch as Ms. Pensler blows up WesDivest’s progress just before she leaves Wesleyan.

when you focus on the one Jewish state but ignore the 20 surrounding Arab states that deny basic rights to their citizens, it’s a textbook definition of Anti Semitism.