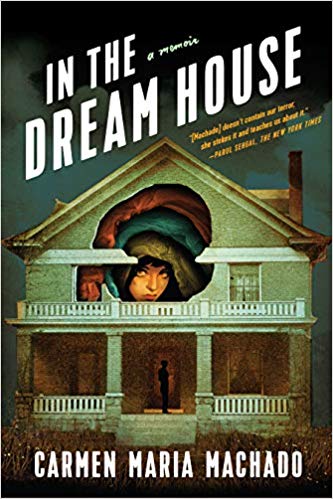

c/o amazon.com

Content warning: Domestic abuse

There is a woman standing in the doorway of the house on the cover of Carmen Maria Machado’s novel “In The Dream House.” Her tiny frame is hardly noticeable against the backdrop of the looming house. But if a person looks closely, they will see her standing there with her shoulders turned inwards, as if she is about to go back inside, and only came out for a moment to look at the reader. It is a picture that is at once menacing and warmly inviting, much like the experience of reading the story that Machado has woven together. “In the Dream House” is an accumulation of raw feelings, philosophical contemplation and political commentary that is worthy of its readers’ attention.

“In the Dream House” is a memoir written from the second person point of view. This is a choice that helps to connect readers to Machado’s experience, yet also means that the memoir reads as if it is a letter that Machado wrote to herself. The memoir is made up of short chapters with titles that all begin with the phrase “Dream House As.” For example, there is “Dream House As Lesbian Cult Classic;” “Dream House as High Fantasy;” and “Dream House As Thanks, Obama.” Each chapter adds another layer, albeit non-linear, to the story that Machado tells of an abusive relationship that she experienced with another woman. Machado never names her former partner, instead referring to her mostly as “the woman from the Dream House”; “The Dream House” referring to the home that the two women shared together for a period of time.

The Dream House takes many forms and functions in the memoir. Machado uses it as a representation of what a house that serves as a home for two lovers could be, should be and actually is, in her experience. It serves as a setting for her most wild romantic fantasies, and the harshest realities, and truths that make up her relationship with the woman she shares the house with. She places much attention on the stereotype of the idealized, utopian nature of same-sex relationships, and the pressure such an ideal placed on her when she herself felt trapped in a relationship that was the complete opposite of utopian.

The focus Machado places on the intersection of fantasy (think Grimm fairy tales) and reality makes for one of the most thought-provoking aspects of the memoir. She repeatedly includes footnotes that cite certain motifs from the six-volume catalogue “Motif-Index of Folk-Literature: A Classification of Narrative Elements in Folktales, Ballads, Myths, Fables, Mediaeval Romances, Example, Fabliaux, Jest-Books, and Local Legends.” Machado uses the footnotes as a sort of dry, witty commentary on the events that happen in her life. She includes citations of motifs like “Falling in love with person never seen” and “Mother throws children into fire.” Machado’s footnotes provide intriguing insight into how she processed and understood the things she experienced, in addition to their function as a genuinely creative way for an author to provide further commentary dissecting her life and writing.

The inclusion of footnotes is not the only way in which Machado revolutionizes the format of the memoir. In what is arguably the most creative and emotionally impactful chapter of the entire book, Machado devises a choose-your-own-adventure system in which readers can decide how they would respond to certain situations that Machado encountered with the woman from the dream house. Machado lays out a list of options readers can choose and the page they should proceed to that corresponds with their choice. The resulting, intensely dizzying experience that results deeply drives home the emotional strain and sheer complexity of the toxic cycle of abuse that Machado experienced. The format also shows just how aware Machado is of every aspect of her readers’ feelings, an awareness she uses to masterfully manipulate the reading experience they have. She knows the empathetic frustration readers will feel as she wants to leave her abusive partner but can’t. They can try to escape it, they can try and drive it away, but as Machado writes of one possible outcome, “That’s not how it happened, but okay. We can pretend.”

“In The Dream House” in some ways puts a spotlight on writing itself; the process of writing, the purpose and the power that comes with it. Readers are able to observe aspects of Machado’s writing process that she details in some chapters, as well as reflections on the time she spent in the famous University of Iowa MFA program. In addition to providing readers with some insight into a community of writers, Machado’s work highlights the extent of what writing can accomplish. The very existence of the memoir that Machado has written is an explicit act of defiance and courage on Machado’s part: readers learn that her abuser forbid her to ever write about one instance in which she acted abusively towards Machado. Yet the fact that readers are able to read those very words shows Machado’s present ability to reject the demands of her abuser.

Machado recognizes the societal power that writing holds, a power that she emphasizes through her inclusion of chapters that focus on the lack of writing about queer domestic abuse and sexual assault. The dearth of books about abuse in same-sex relationships is part of what makes Machado’s memoir so remarkable. Not only is Machado’s writing gorgeous, honest and simply human, it’s also on a topic that has simply not received the attention that it should in the literary world. “In the Dream House” is a momentous, remarkable step towards addressing the lack of memoirs portraying abuse in same-sex relationships.

Sophie Wazlowski can be reached at swazlowski@wesleyan.edu.