If a person is lucky, they might have the kind of experience Sami does in André Aciman’s novel “Find Me” more than once in their life. It’s the instance where two people walk by one another on a street and both turn around to catch one more glimpse of the person that just passed them. It’s locking eyes with a stranger across a crowded train and walking away thinking if only you had been stuck in an elevator together, or if your flight was cancelled and you had to spend a night in stuffy waiting area—you just might have stayed together forever.

Sami arrives on his train to Rome expecting to spend his time reading. That is, until a woman sits down next to him. They strike up a conversation, and are instantly taken with one another. The encounter is so perfect it seems unbelievable at certain points over the duration of the story. Some of that unbelievability stems from the number of times that Aciman plainly states how much Sami loves everything she does. His love is not shown, but told, making their affair seem less authentic and believable at times. However, despite the unsubtle nature of Sami’s infatuation, the beauty of Aciman’s writing does not make it difficult to be swept up in the dream of two lovers managed to find one another on a train by sheer chance.

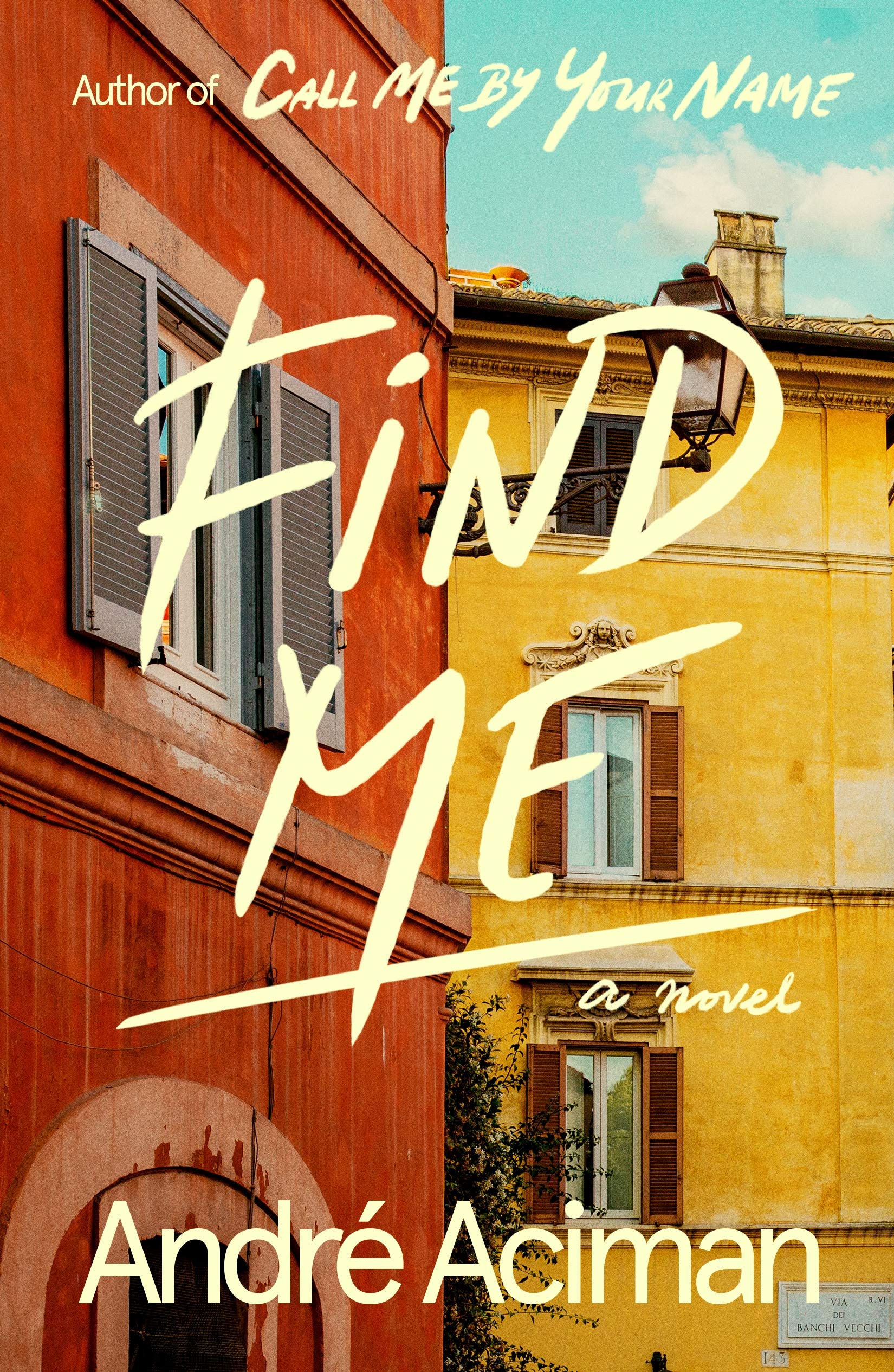

The most jarring aspect of the beginning of “Find Me” is, of course, that it starts with Sami’s story. The novel is, after all, the sequel to Aciman’s bestseller “Call Me By Your Name,” which focused on the relationship between Elio (Sami’s son) and his lover, Oliver. Elio’s narration begins just under halfway through the novel. Aciman has chosen to bury the story of the relationship readers are most eager to experience again, making it a prize to be won by getting through Sami’s story first.

Sami’s story is not an entirely necessary component of the story, at least not in the amount of words it’s given in the novel. Elio’s story and his father’s are hardly connected except for in a slight plot point revealed at the end of the book, begging the question of why Aciman chose to devote such a large part of the novel to a story most readers most likely simply do not care about as much as Elio and Oliver’s haunting romance.

An exploration of the complex relationship between parent and child is present throughout the novel, a theme Sami’s story somewhat embellishes. The similarities between Sami and his son are unmistakable, whether they were intentional or not. They speak in the same way and think the same way. They are different people, but the shared qualities they have drawn attention to the intimate connection only a parent and child have. Aciman’s analysis of the parent-child relationship makes for one of the most thought-provoking points in the novel (of which there are many)—especially the question he poses to readers of how well a child can ever know the person who raised them, through the story of Michel, a man named Elio meets and falls in love with at a concert in Rome.

Throughout the course of the book, Michel is trying to untangle his father’s mysterious life. When Michel’s father died, he gave his son a piece of sheet music he claimed was his most prized possession. The music leads Elio and Michel to wander through the mystery of a Jewish man and his dangerous relationship with Michel’s father and his Nazi-sympathizing family, a captivating subplot that certainly adds to the novel.

It is in the sections written in Elio’s point of view that Aciman’s writing shines its brightest; Aciman is a master at writing about love. In just a few sentences he transports his readers to dimly lit cafes in Rome where Elio and Michel work past small talk, and the shy awkwardness of discovering who a person really is for the first time. He captures the interplay of nerves and desire that mark the early stages of relationships, making the affair between the two men seem so real that readers feel as though they could be sitting at the same table as the characters, enjoying a glass of wine with them.

Aciman does, eventually, bring Elio and Oliver together once more in the final chapter of the novel. The novel, like its characters, has a newfound, wiser outlook on love. The Elio and Oliver in “Find Me” are not the same young men who fearlessly let themselves fall into a love they knew might not last in “Call Me By Your Name.” The Elio and Oliver in “Find Me” have seen the world and have come face to face with often unromantic reality of the world. They have learned what it is to live with love, and without it.

As in “Call Me By Your Name,” the lovers grapple with the difficult questions and circumstances reality places before them. They must decide what in life is worth living and who they should love with the one life that they have—who is worth loving, in this messy world full of missed opportunities. In “Call Me By Your Name,” Elio and Oliver had to decide whether or not to speak or to die. “Find Me” is a novel in which they have come to terms with the fact that they will die, so they too must speak, before the time comes when they no longer can.

Sophie Wazlowski can be reached at swazlowski@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply