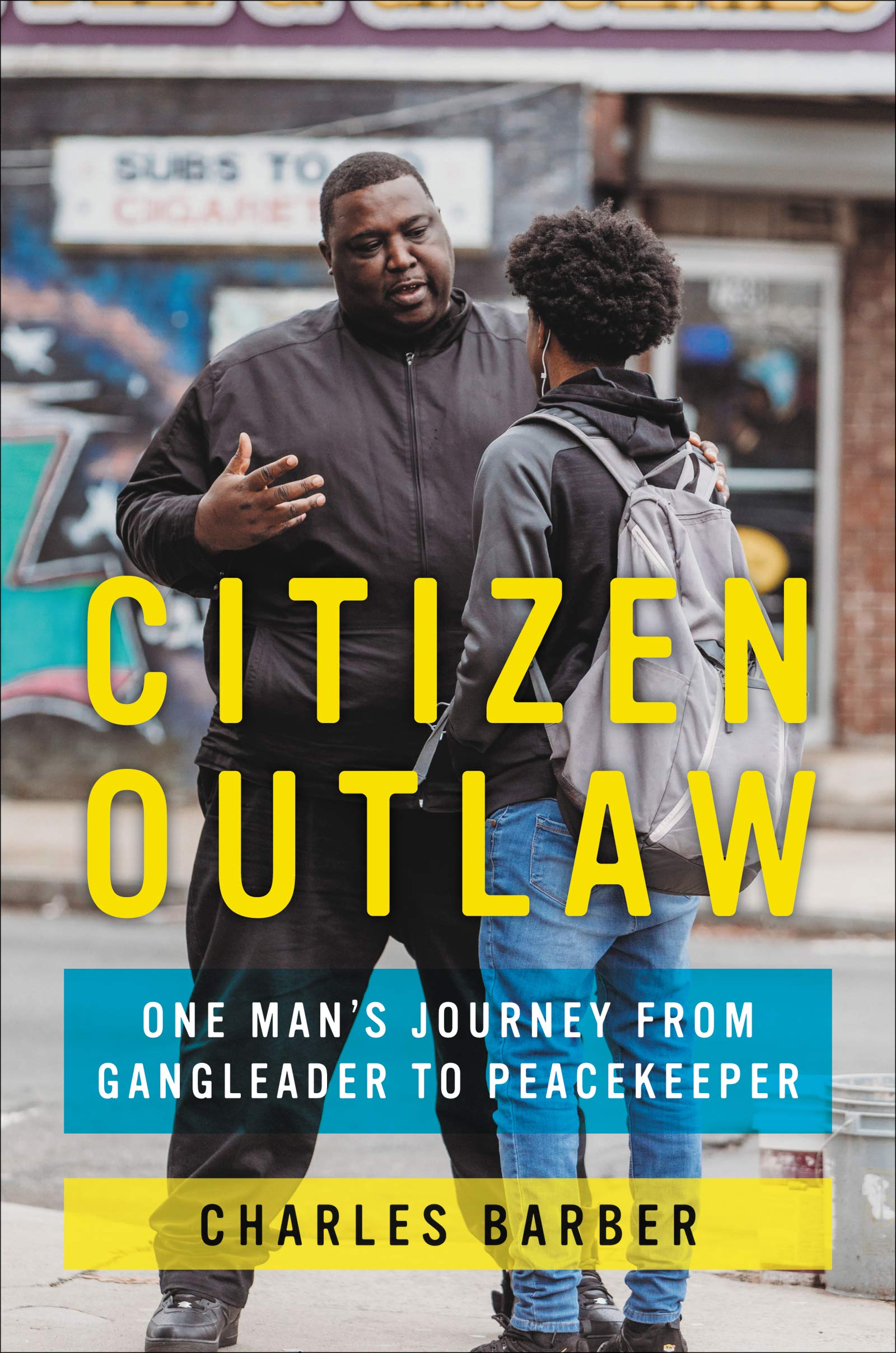

On Friday, Nov. 1, Professor Charles Barber held a reading from his new book, “Citizen Outlaw: One Man’s Journey from Gangleader to Peacekeeper.” The book follows the story of William Outlaw, a former gangster turned peace activist, and addresses some of the most important public health and criminal justice issues in Connecticut and across the country. Barber shared the podium with Ivan Kuzyk, the Director of the Connecticut Statistical Analysis Center, therapist Richard Whitmire, Executive Director of the Connecticut Violence Intervention Project Leonard Jahad, and William Outlaw himself, each discussing their experience with and contributions to the project.

Barber and Outlaw were introduced in March 2014 by Kuzyk, a crime analyst who had heard of Outlaw and was compelled by his story. Outlaw contacted Kuzyk looking for a writer, and Barber accepted the offer. After their introduction, the two continued to meet weekly for a period of five years.

Kuzyk offered some background on Outlaw’s life. Also known as June Boy, Outlaw ran an effective street gang in New Haven in the 1980s called the Jungle Boys. After his involvement in a homicide, Outlaw was sentenced to 85 years in prison. He did time at some of the most violent prisons in the country. Despite his notoriously difficult-to-control character, Outlaw managed to reduce his sentence to 21 years on appeal.

“He emerged a completely different man,” Kuzyk said. “You can see this if you read the book.”

The book is divided into two sections, Outlaw and Citizen. Reading from the latter, Barber recounted a turning point in Outlaw’s relationship to violence. One summer night in 1988, three members of the Aryan brotherhood killed two people whom Outlaw was friendly with in the prison. These killings triggered a lockdown of the prison, and a lockdown on Outlaw’s nonchalance towards violence.

“Outlaw had been around shootings and stabbings his whole life, but the murders on A-Block hit him in a way that nothing else had before, perhaps because he had nothing at all to do with the beef,” Barber writes. “He was able to see violence afresh.”

In the wake of the killings, Outlaw was introduced to a critical figure that would expedite his transformation. All prisoners formerly involved in violent crimes were required to see a therapist. While Outlaw found it absurd to share his feelings with another man at first, the eccentricity and jovial character of social worker Richard Whitmire helped change his mind and the two soon developed a strong bond. This was the first time Outlaw confronted and began to remedy his trauma; he talked of guilt, pain, anger, and the feeling that violence was normal. Whitmire pushed him to confront and express his latent anger, and to construct a new narrative for himself.

“The entirety of this message was difficult for Outlaw to process, but once he took hold of it in his typical all-or-nothing style, it was remarkable how quickly the bitterness faded,” Barber said. “Outlaw felt a kind of slow melting away of the anger.”

Leonard Jahad, Executive Director of the Connecticut Violence Intervention Project (CT VIP), described working with Outlaw after his release from prison. While his co-workers expressed concern at Outlaw’s return, Jahad did not doubt that Outlaw was changed by his experience. The organization wanted him on their side. Outlaw consented and began to work relentlessly on violence prevention, particularly by giving presentations to and engaging with the youth.

“In his presentations, it was always about redemption, and about taking responsibility for what he did,” Jahad said. “He wanted to help clean up the streets that he helped tear up some 20 years prior.”

Outlaw himself spoke of his aspirations for the book and for his activism. While he hopes that his work will impact the levels of violence in urban areas, he also hopes that it will impact suburban areas. He is intent on maximizing the scale of change.

“We are going to do some fine things in the state of Connecticut,” Outlaw said. “Not just against gun violence and gang violence, but against all violence.”

In a post-talk Q&A, a member of the audience questioned whether people, especially the youth, are suspicious of Outlaw, and how Outlaw cultivates trust. Outlaw quickly replied that the first step is to never question what happened or whether the subject was involved. If the police want to remedy youth crime, arrest is out of the question.

“The police department comes to us—we say give us the kid,” Outlaw said. “You want us to work with the kid, give us the kid.”

Another element involves respect and reputation. Outlaw and CT VIP spent years cultivating relationships with both the police force and the community. For Outlaw, this process is facilitated through self-confrontation. It’s about acknowledging your faults and your past and holding yourself accountable—only then can you begin to set standards for others.

“I keep going back to the man in the mirror in the book,” Outlaw said. “You have to hold up the mirror to your face for one minute and really look at yourself. Then, you’re going to start saying, ‘Wow.’”

Steph Dukich can be reached at sdukich@wesleyan.edu.