In “Forever Seeing New Beauties,” Kahn Unearths the Work of an Unappreciated Impressionist

“There is a punch line to this story,” art historian Eve M. Kahn promises in the first sentence of “Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907.” The art book, which was published by Wesleyan University Press this past September, is the first time that the largely unknown artist Williams has been given exposure in any significant way.

The punchline, as it turns out, is the way in which Kahn first came upon Williams’ work. She was visiting her mother, Renee Kahn, in Stamford, Conn., when she came across a dark, brooding, landscape painting that she was fascinated with, one which was ostensibly signed “M.R. Williams.” Kahn, who was The New York Times’ Weekly Antiques Columnist from from 2008 to 2016, looked further into M.R. Williams and was fascinated by what she found—fascinated enough, as it turned out, to devote a whole book to it. However, Kahn discovered that her mother’s painting was not, in fact, an “M.R. Williams” but rather, an “M.P. Williams,” the work of M.R.’s random and unaccomplished doppelgänger. But by then, Kahn was already far down the rabbit hole.

“The family owns perhaps 100 of her 120 known surviving paintings and pastels plus thousands of pages of her vivid letters to friends and family,” Kahn told The Argus. She soon discovered that these letters, particularly, constituted an incredibly rich archive.

“For hardly any other 19th-century artists, men or women, do we know what they were thinking, wearing, eating, reading, wondering about, critiquing in the art world, and trying to capture with paints or pastels, on a particular day,” Kahn said. “And she was funny, feisty and observant, and never self-pitying.”

M.R. Williams’ work itself is certainly notable for a few reasons. First, her pastel landscapes exhibit a level of abstraction for her time that is extraordinary, calling to mind the work of fellow Impressionist luminaries such as Whistler and Monet. Second, it is extraordinary to see portraits of women rendered at this time that are neither through a male gaze, nor through a particularly feminine gaze. Kahn notes that Williams expressed a desire to wear men’s clothing and had she been born later, she “might have been openly lesbian…or gender nonconforming.”

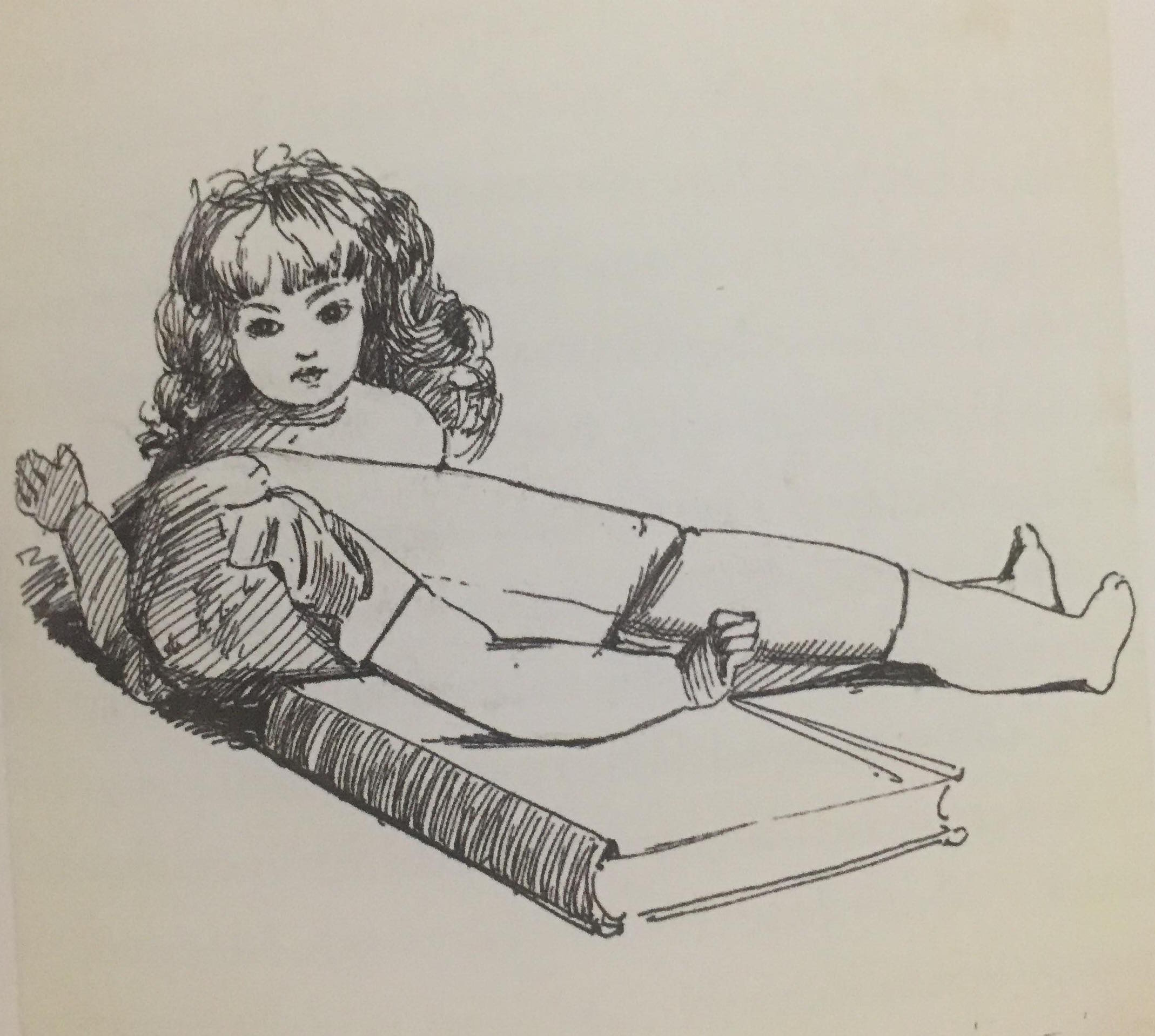

Consider Williams’ portrait 1895 portrait of her Smith landlady, an austere older woman seated in a high-backed chair against a mysterious, multi-tonal green wall. We’re not used to seeing women like this: women who are over fifty, middle-class, and appear powerful but not necessarily sexual. Or one of Williams’ most interesting pieces, “Self Examination,” an undated sketch “of a decapitated doll impassively gazing at its body parts.” This sketch was created during the long 19th century—the period of 1789 to 1914—which is nothing short of remarkable. Its conceptual strangeness, and focus on interiority and symbols of femininity, seems more in line with the kind of work created by second wave feminists than with that of anyone else doing 18th-century portraiture. We can read the piece as a symbol of femininity being examined, or the destruction of a childhood, or even the deconstruction of a signifier and its signified. However we choose to interpret the sketch, it is playfully thoughtful, topical in a way that is extraordinarily precocious for its time. And throughout all of M.R. Williams’ pieces is an excellent understanding of color—of light foggy blues, rich deep greens, bright pulsing reds, all richly layered, all executed with careful attention to alteration by light.

“Her landscapes come the edge of abstraction,” Kahn wrote in an email to The Argus. “She turned Maine coastlines into wisps of seafoam and veined rocks, and she rendered stucco walls and tile roofs on Italian buildings as white and red daubs. And in her portraits, the backgrounds are often just striations in glorious multiple colors.”

It is Kahn’s unearthing of Williams’ many letters and diary entries, though, that is perhaps even more important to our understanding of the realities of being an artist, and one who is not male, at the time that Williams lived and worked. Kahn confirmed that her background as an antiques columnist helped her to pursue the story.

“I had no fear of being a journalist-detective, cold-calling people whose ancestors knew Mary,” she said.

The letters provide an intimate glimpse into the realities of what it looked like to travel and to make a living as an artist. Williams interacted with celebrities of the time, ranging from J.M. Whistler in London to the notorious King Leopold of Belgium. And she grew increasingly tired of the repetitiveness and politics of academia. Through her letters, we can begin to understand a woman who can scarcely be considered a woman of her time, but nevertheless had to contend with the many unreasonable constraints of her time.

As for Kahn, she’s already at work on a new project about another unappreciated woman.

“I’m obsessed with the Kentucky-born writer Zoe Anderson Norris (1860-1914), who reinvented herself in middle age as a New York-based journalist,” Kahn said. “She published a semi-monthly magazine, ‘The East Side,’ which documented immigrant poverty, and she was known as the Queen of Bohemia.”

If Kahn’s last book is any indication, she’s sure to be a woman worth investigating.

Dani Smotrich-Barr can be reached at dsmotrichbar@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply