c/o wesleyan.edu

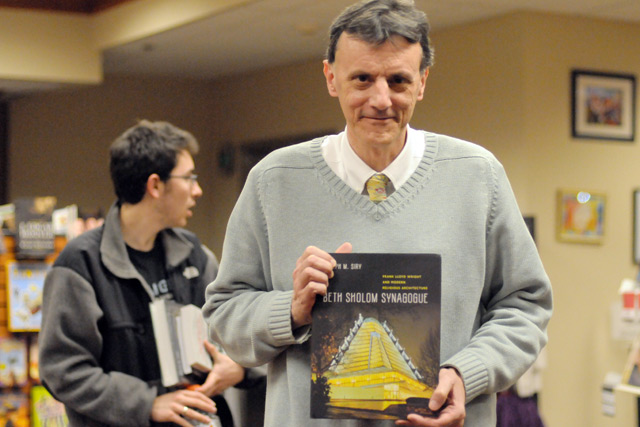

Packed bookshelves spanning wall to wall seem to contribute to the architecture of Professor of Art History and Kenan Professor of the Humanities Joseph Siry’s office, which is on the second floor of Boger Hall. Having published multiple books covering Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs and the Chicago Auditorium Building, as well as works on Louis Sullivan and the Prairie School, Siry is a leading architectural historian and acclaimed professor at the University. As part of our continuing series on professors’ favorite reads, The Argus sat down to see what books have been on Professor Siry’s mind and what he’s working on outside of the classroom.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Argus: Do you have any architecture books that you’ve read recently that you think are hidden gems that you’d like to endorse?

Joseph Siry: Well, here is a book written by a Wes alum. [pulls “Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory” from the shelf.] Carla Yanni. She was a thesis student. She just got a major award from Rutgers University as an Outstanding Teaching Scholar, and she’s class of ’87.

A: What period do you focus your research or work on?

JS: Well, it’s mostly modern architecture of the 20th century. Most of these books are on Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright.

A: Do you focus your work on mostly American architecture?

JS: The teaching spans from Greek and antiquity through the 21st century. The course I’m teaching this semester is Energy and Modern Architecture. “The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment” is one of the first books that talked about the history of environmental systems and architecture. For contemporary green building, that’s a pretty good title.

A: Do you remember what the first books were that you came here with?

JS: I have my original college textbooks with math and physics here, going back to my freshman year. And I have notebooks from my freshman and sophomore and junior year here.

A: Where did you go to undergrad?

JS: Princeton.

A: Ah, gotcha. Do you ever look through the old notebooks from your undergrad years?

JS: Not much anymore, but they were important for a long time. For some reason, they’re comforting to have here.

[pulls book from shelf.]

JS: Here’s a really outstanding book. This is a book, “Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time” that we as Wesleyan architecture professors collectively published and created. Clark Maines just retired, Phillip Wagoner…and Nadja Aksamija [are] just down the hall, so they co-edited this work together, which came out in 2017.

A: Does the Wesleyan architecture department specialize in a specific area?

JS: Well, each of us does quite different things. Phillip Wagoner does South Asian art and architecture, Nadja Aksamija, as you may know, does Renaissance, Italian Baroque art, architecture. So, for a school of Wesleyan’s size, we have had for many years, eight full-time positions in art history, and three of those were non Western: one in South Asian, East Asian, African. So for a school our size, that’s really unusual to have that range of coverage.

A: How did you know you wanted to study American architecture?

JS: Well, I think part of it was that I grew up in Washington D.C., so I was surrounded by major works of public architecture, namely prominent monuments. I think Washington’s architecture made a huge impression on me. Washington is its own distinct environment. It’s mostly federally controlled.

A: Architecture must be an interesting field because it seems like an intersection between a lot of different disciplines: you have to know zoning, policies, and art, and mathematics, and physics. Do you see those disciplines interacting in the field?

JS: It does mark a convergence with a lot of different fields. I mean, there’s always a political component, and there’s a financial component. There are all kinds of issues of class and urban development, and environmental issues. That’s my current interest—I’m writing a book on air conditioning and modern architecture.

A: Have you come up with anything related to that that has surprised you so far?

JS: The green movement dates back to the 1970s. But, before that, there was an emphasis on efficiency, and there was a much more broad acceptance of large, energy-consuming systems, because they were drivers of economic activity. They were enablers of large-scale economic activity, like in factories or other businesses, office buildings, movie theaters. Those all depend on air conditioning, so there were a lot of reasons for productivity for why people wanted to build very energy-consuming environmental systems. It wasn’t until the 1970s that things really changed. They reconsidered it as something more about conservation. Climate change was sort of [unrecognized] until the 1990s, but now it’s all changing.

A: For students who have not considered taking an architecture class before, what would you tell them to convince them to take a class in the architecture department? What do you find compelling?

JS: To me, what’s compelling is that we live our whole lives in relation to a built environment. I think for most students who come into courses that I teach or that are taught by people interested in architecture, that may be the first time where they’ve thought critically, analytically, historically, about that, or technically. So, they may not all be architects later on, or they may not all be historians of architecture like Carla Yanni or Paul Lewis. But we are involved as citizens and as consumers of architecture. And we make all kinds of decisions about the built environment throughout our lives, how we’re going to live, where we’re gonna live, what kinds of homes we want. And to me, the built environment is a huge factor in the quality of life, and how you engage with it and understand it, and what your lifelong relationship is to it intellectually, critically, emotionally, physically, socially—that’s always going to be there.

A: Do you live in Middletown?

JS: Yes, I live in a 1927 farm house. And I worry about the health of it. It’s been a very successful house for me and my wife. It’s a house that is not like the other houses around it cause most of them are built much later, 1970s. It’s really dating from a period when that part of Middletown is called the South Farms District. It was a Quayside rural environment. So we used to see horses and tractors going, by but mostly in the last 19 years, downtown has been transformed as more restaurants have come in and less retail stores, because retail overall has been greatly shrunken due to internet commerce, as I’m sure you know.

A: Have you noticed that the shift to the digital world has influenced architecture?

JS: Oh sure, [the internet] has completely transformed it in the last 25 years. I’m thinking I will teach a course on contemporary world architecture and the way buildings are designed and built and fabricated and analyzed, it’s all into the digital realm now. When I was trained in architecture, drawings were still handmade and people learned at drafting boards about making them. Now, that’s completely transformed. To be able to envision buildings virtually and to be able to test how they’re going to work thermally—all this is done with software in the digital realm. So, contemporary passive houses, very low energy-consuming houses—they’re all modeled digitally for thermal performance. There are all kinds of ways in which digital culture is transformed architecture and attitude since the early ’90s.

A: Do you see that shift as a positive? I feel like I hear from a lot of professors in more artistic disciplines and in the humanities that there’s a tension between the digital realm and the humanities. Do you see it as a tension or just an influence?

JS: Well, it is powerful. You can make forms that are vastly more complex to draw into fabric tape with digital tools than you can without them. And if you have a building on digital platform and everyone involved with the building process can work from that platform. So it’s not just the architect and the engineers, it’s the fabricators, it’s the contractors, and they can all share information and think through all the issues of realizing a building with particular forms. That was much harder to do before. And that information sharing through digital spaces is just the norm for the way architecture is done now. It has been for 20 years. It’s transforming the way people think about possibilities for spatial and material form.

An earlier version of this article contained errors which have now been corrected: The author of “Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory” is Carla Yanni. Prof. Wagoner’s name was previously misspelled as Wagner. An earlier transcript mistook “they” for “we”: Nadja Aksamija, Clark Maines, and Phillip Wagoner co-edited “Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time.”

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lwgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.

Sara McCrea can be reached at smccrea@wesleyan.edu and on twitter @sara_mccrea.

1 Comment

Susanne Fusso

Just a few corrections: It’s Carla Yanni, not Clara. Prof. Phillip Wagoner (not Wagner) is not retired. Prof. Siry contributed an article to the Palimpsests volume but was not one of the co-editors. Prof. Siry has taught a course on contemporary world architecture for over a decade.