Content warning: Sexual violence

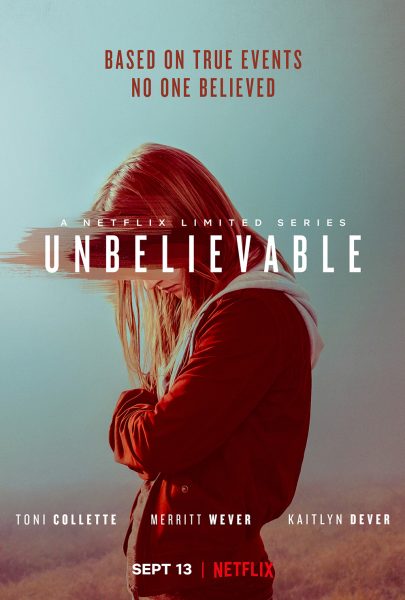

“Unbelievable,” a crime drama miniseries that premiered on Netflix last week, wastes no time in introducing viewers to its premise. The pilot episode opens on Marie Adler (Kaitlyn Dever) in the aftermath of a brutal sexual assault. For the first third of the hourlong episode, we watch a shell-shocked Marie describe her rapist—a stranger who broke into her apartment and threatened her with murder if she screamed—over and over again, first in her apartment to the officers who responded to her 911 call, then in a hospital to the nurse administering her rape kit, then at the police station to a brusquely detached detective. By the fifth retelling of the assault, viewers can practically feel Marie’s numb exhaustion.

“Unbelievable,” which was co-created by Susannah Grant, Ayelet Waldman, and Michael Chabon, is based on the true story reported by T. Christian Miller and Ken Armstrong in their Pulitzer Prize-winning piece for ProPublica, “An Unbelievable Story of Rape.” Both the show and the original piece follow two separate narrative threads, which only merge towards the end of the story. The first storyline, which is introduced in the opening scene, follows Marie’s miserable treatment at the hands of the criminal justice system in 2008. The detectives assigned to her case (played by Eric Lange and Bill Fagerbakke) quickly move from disinterest in Marie’s assault to open disbelief. Their skepticism is shared by Marie’s former foster mothers, who find her relatively calm demeanor suspicious. Brief flashbacks make it immediately clear to viewers that Marie is telling the truth, but as the cops question her over and over again—growing more and more accusatory each time—details of her story start to change, until finally the officers charge her with filing a false report.

Watching Marie’s interactions with law enforcement is an enraging experience—one that is only partly assuaged by “Unbelievable’s” second storyline. This plot begins in 2011, three years later, and follows Detectives Karen Duvall (Merritt Wever) and Grace Rasmussen (Toni Collette) tracking a serial rapist—you can probably guess how their storyline ultimately intersects with Marie’s. But unlike the cops Marie has to deal with, Duvall and Rasmussen are dedicated to bringing the attacker to justice. The opening of “Unbelievable’s” second episode mirrors the pilot, with an extensive scene of a rape victim named Amber (Danielle Macdonald) being interviewed by Duvall. But in this case, Duvall treats Amber with patience and compassion, answering her questions and giving her ample time to process her own thoughts. The scene serves as both criticism of and relief from the unkind handling of Marie’s case.

There is much to admire about “Unbelievable” and the way it handles the topic of sexual assault. The show avoids the sensationalism with which rape is often treated onscreen, skipping graphic depictions of assault in favor of a greater focus on its aftereffects. For Marie (whose painful storyline is bolstered by an excruciatingly good performance from Dever), these aftereffects are particularly brutal, including not just the trauma of the original event but the ostracism that results from being labeled a false accuser. The result is a show that is uncommonly compassionate towards survivors and manages to include both a damning indictment of the misogyny that permeates law enforcement (in the 2008 storyline) and a hopeful portrayal of what justice for survivors could look like in an ideal world (in the 2011 one).

However, the show’s single-minded commitment to making a point sometimes results in a grueling viewing experience. At times, the show feels like watching a group of very talented performers act out a Wikipedia article. This is never more evident than when Detectives Duvall and Rasmussen find increasingly contrived ways to work statistics about sexual assault into casual conversation, which they do with some frequency.

It’s certainly true that “Unbelievable” deserves commendation for its stark portrayal of the lasting consequences—physical, emotional, social, and financial—of rape. But I already know what percent of reported sexual assaults is considered unfounded (5 to 10) and what percent of male police officers have been reported for domestic abuse (40). I was already familiar with the story of the real-life Marie Adler before I saw “Unbelievable”—and with the story of Chanel Miller, and that of Christine Blasey Ford. Watching the show, I felt some relief at Marie’s happy ending, but mostly all I felt was exhaustion at the thought of the scores of Maries who get no such closure. I’m glad “Unbelievable” exists, and I’m sure there are other viewers who will find it both cathartic and educational, but I didn’t learn anything I didn’t already know.

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply