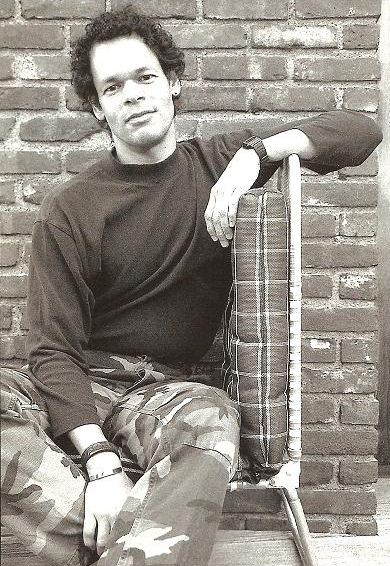

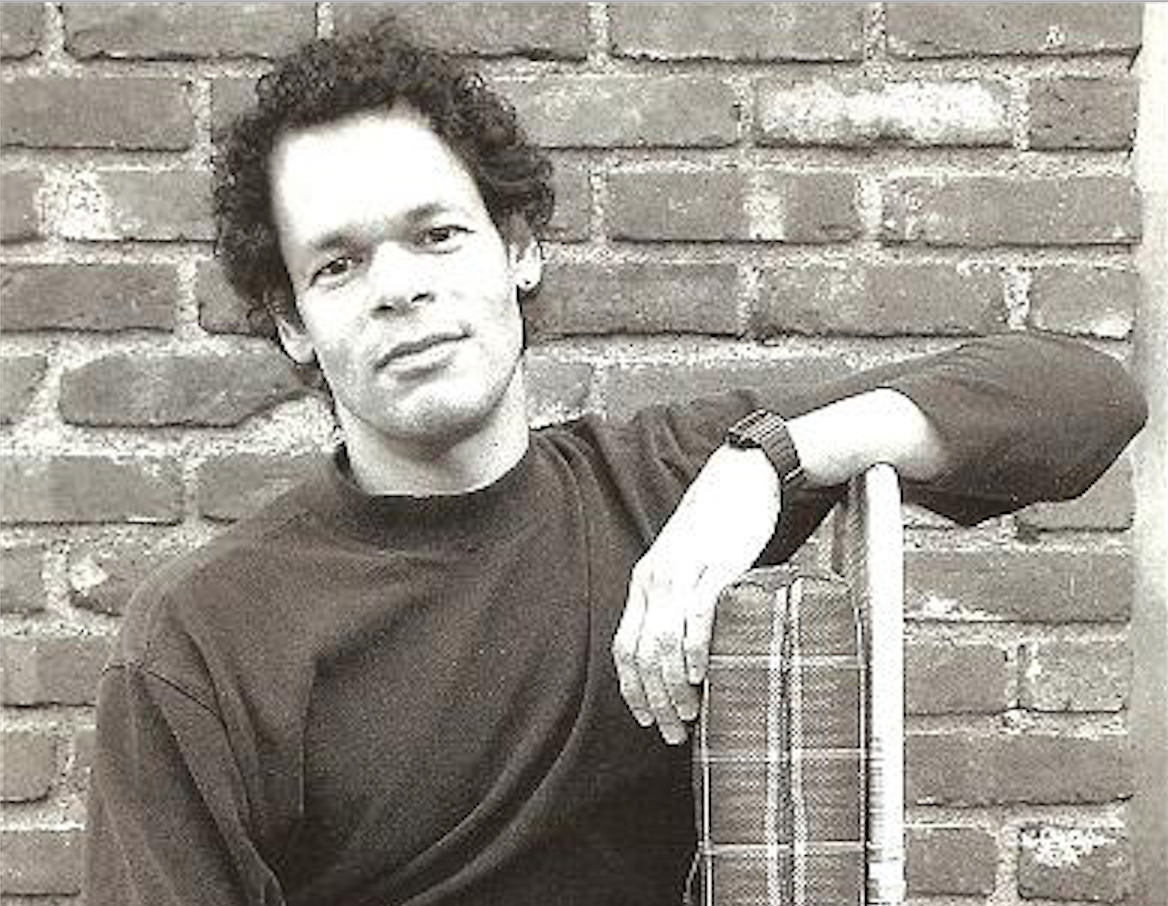

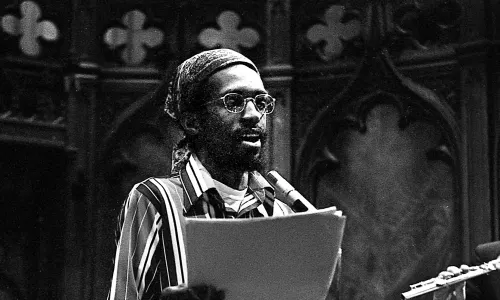

Visiting Professor Edwin Sanchez Discusses Career and Writing Process

Visiting Artist-in-Residence in Theater Edwin Sanchez has written internationally produced plays, as well as scripts for film and television. His first novel, “Diary of a Puerto Rican Demigod,” was published in 2015. He has won the National Latino Playwriting Award and several New York Foundation for the Arts Playwriting Awards, among other awards. Sanchez is currently a visiting professor at Wesleyan, teaching “Introduction to Playwriting” this fall, and “Advanced Playwriting” in the spring. We sat down with him to talk about his work and his writing process.

A: How did you first get started as a writer or realize you wanted to write plays?

ES: I was in my first play…and I was a chubby kid. There literally was no one else in the show that was chubby, and I was chubby, so they said, “Okay, we’ll take you.”

A: Where did you grow up?

ES: Puerto Rico. And I fell in love with the [theater] community, so right after that, I wrote my first play and I gave it to the director. And what I basically did honestly was rip off the play I had just been in, totally copied it. And then I re-worked it, and it became something different. And I would write for a while and stop, write for a while and stop.

A: And what do you think made you go from being in a play to wanting to write your own?

ES: When I first got to New York, I wanted to be an actor, but all the roles there were pimp, drug dealer, or gang leader, and they didn’t excite me. And I said, I really want to write the characters I don’t see on stage. And so that’s when I started writing, and I really fell in love with it. Because you have the power then.

A: Were there any playwrights or authors that you particularly looked up to?

ES: Honestly, I hadn’t even seen a play. No, I think I saw one play before I was in one. It was a kind of young theater play called “Young Thomas Edison,” and I had to take a school bus to get to it. I was like 12 or 13. But that was it. Theater was way beyond our means. Theater tickets were $200…it was inconceivable. So I just started writing because the beauty of plays, even if no one puts them on…[is] you still have them. And then you just start sending them out.

A: And is there anything about the medium of a play specifically that seems to make sense to you?

ES: Yes, it’s happening while you’re breathing. And you’re on stage, and you’re all breathing the same air, and it’s different every time. The chemistry changes, and that’s really exciting. And the best part is when you hear that audience gasp. They gasp because you just said a truth that reflects them. And that is the best experience, it really is.

A: And do you feel like sometimes the way in which someone plays a character will surprise you?

ES: Absolutely. I am very aware of the contribution actors make to it. There was one actress who, the character in the play had made a promise, “Please bring my sister back because my husband really loves her, and if she comes back I can leave him without a guilty conscience.” And she made a promise to God…and then…she found out the sister was dead. And when she found out the sister was dead the actress—I didn’t write this—she just looked up at God and started laughing, like, “Wow, I should have said ‘alive,’ who knew I had to be that specific?’” And I never would have thought of that, and that was really kind of cool.

A: And I know you’ve written some 10-minute plays, which is a crazy concept.

ES: I’ve written some one minute plays. Those are insane.

A: How do you get an audience to be invested in characters they know for that short of an amount of time?

ES: You sort of have to hit the ground running when it’s a minute. When it’s 10 minutes you have a little more time. You have to introduce right away what they want. And they also know how to take 10 minute plays—they’re sort of focused for that…

A: So stakes are really important?

ES: Exactly, so they immediately know where they’re going. I did a one minute play for a one minute play festival. It was insane because they discouraged people from applauding in between, they were trying to do 60 plays in 60 minutes, and so you couldn’t digest one before the next one started. And every so often one would really land personally with you and you would say, that is really good, but then you’d say “oh wait there’s a new one!”

A: And I know you’ve also written a novel. Where did the impetus for that come from?

ES: I just wanted to have a bigger canvas. It was kind of fun to write something where you could say, “and the subway arrives”…you know, because you can’t have the actual subway car onstage. There are a lot of things you can’t really do onstage and you can use your imagination and that’s really great but it was really freeing…I look at it as using a different row of colors in the crayon box. I mean you’re still coloring, but you’re like, oh these are kind of cool, and it’s just like writing a film script, where its like okay now I use these colors and so…

A: What’s the premise of the novel?

ES: The premise of the novel is a former chorus boy who was in one show. He was 18 years old and he becomes involved with the richest man in the world, and he stops growing up. Because if everything is given to you, you never have to do anything, and for 20 years it’s like that until he gets traded in for a younger model, and all of a sudden it’s: how do you start up where you left off, and grow up again. And he had no money because he refused to take any money from the guy, and he basically winds up living in his parent’s basement apartment, has the worst soul-sucking job that you can imagine, and sort of reconnects with all the friends and family he gave up when he went deluxe. And it’s how he grows up.

A: What makes him a demigod?

ES: Because he was married to a god—a financial god. And he knew he wasn’t big enough to be a god, so he said that makes me a demigod. And throughout it all he still loves the guy.

A: I’m wondering if often when you start writing, you start with characters or with a scenario that you think would make for an interesting plot.

ES: I always start with the character first. I don’t know about you, but every so often if you’re sitting on a subway or something, and look across from you and see two people having a conversation but can’t hear what it is, I try to imagine what it is they’re saying. I try to imagine: “Oh God, he’s younger, I can’t leave my wife,” “No, you have to.” Of course, they’re probably saying, “Did you watch that on TV last night?” but you sort of get into the heads of people. But I really am curious about people. That’s the big one.

A: What is it that you like about teaching the most?

ES: I love when people discover their play. A friend of mine put it really beautifully. They said, “When you get the idea for a play, it’s like a house that you can see and you walk up to the house but you don’t know where the door is.” And you’re dying to get inside the house and when a student finally opens the door and goes inside, the difference in them is amazing. I’ve had some students write some scenes that are jaw-dropping, that are like, “Oh my gosh, this is so good.” It’s tough, it’s lonely too, and I would say playwrights are like the caterers. You bring the meal, but when you’re in rehearsal you really don’t eat it. If the director becomes the host, the actors are the guests, and you’re in the background saying, “Yes, I cooked it.”

A: So you have to give up some control?

ES: Yes, but that’s a good thing.

A: And what are you working on right now?

ES: I just finished a new play about a transgender child whose father is dying, and so it’s how both journeys sort of cross, and how they both accept what’s going on…. Also, they’re turning “I’ll Take Romance” into a musical. I haven’t heard it yet. They sent me all the lyrics and they’re supposed to open it in June of 2020 in Ohio.

Dani Smotrich-Barr can be reached at dsmotrichbar@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply