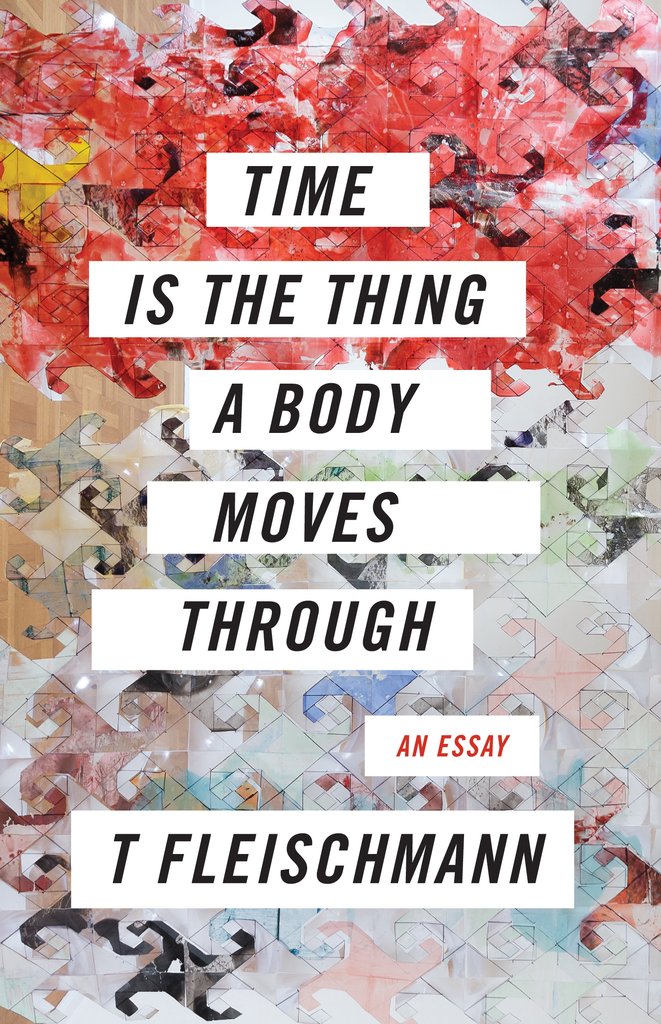

“What can one do with a past?” asks T Fleischmann in their brilliant new book, “Time Is the Thing A Body Moves Through.” “What I mean is, what can we do with our bodies?”

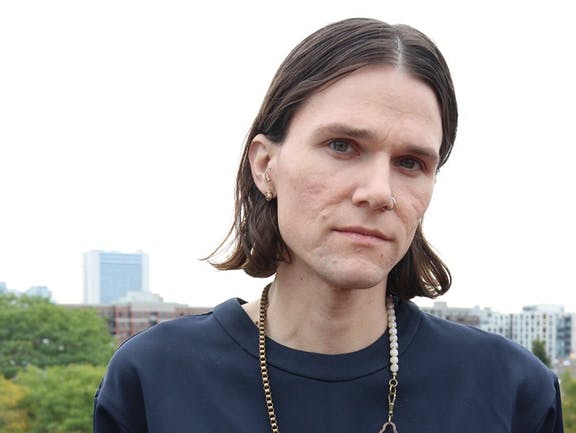

Neither is a question easily answered, but both are certainly worthy of exploration, and Fleischmann is a worthy person to follow as they ponder their experiences with gender, time, art, and language. The book, published by Coffee House Press in June 2019, is an essay of sorts. It is also a memoir of sorts; one as often written in verse as in prose. Aspects are excerpted from various projects of Fleischmann’s; sources are as diverse as a lyric essay on Felix Gonzalez-Torres and a personal sex journal. Fleischmann is the odd author who seems equally easily able to move through any form, with their extraordinary voice acting as the binding force between so many disparate explorations. They seem to have as little affinity for boundaries of genre as for boundaries of gender, and we are better off for it.

The loose structure that Fleischmann reverts to throughout the book is a rumination on artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ famous piece Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). The piece, which has appeared in countless variations and locations across the world, takes the form of a pile of hard candies, which the visitor is instructed to partake in. The piece is dedicated to Gonzalez-Torres’ lover, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS. The candies have been measured to weigh 175 pounds, Ross’ original body weight, and as visitor after visitor takes a piece, we watch the pile diminish, paralleling Ross’ weakened body.

There are several threads that come out of this poetic examination of Ross that carry us through the book; in the wonderfully meandering way that Fleischmann’s writing does, which is to say we don’t care where we are moving so much as how we experience the motion. One of these themes is Fleischmann’s profound awareness of the manifold histories that various locations hold, and how they interact with each of these places. “Like so many of my friends, I found my way to this city [New York] because of what it had been,” Fleischmann writes. “What it had been, we thought, meant what we could be.” Fleischmann seems at times to find respite within cities, but at others prospers in less visible queer communities in rural areas throughout the country.

Fleischmann is one of those writers who makes so many different ways of living seem possible, desirable even. They live in radical anarchist collectives in cities, they take Craigslist jobs in the countryside, “building things, and growing things, and hammer, and tomatoes.” They and their friends seem to operate in a world rich with spontaneity, art-making, community. At times Fleischmann romanticizes these friendships, but they also clarify this romanticization.

“Nearly everyone I know relies on sex work to pay their bills,” Fleischmann writes. “I worry they come across like bullshit flaneurs or something…when the reality is that they are all activists, artists, survivors, finding ways to live under and to fight against a state that tries to legislate our lives away.”

This passage is a demonstration of one of Fleischmann’s greatest strengths as a writer—the ability to speak in terms both personal and sociopolitical, and to make clear that this ability is not a coincidence but a direct result of their and their friends’ gender identities and socio-economic statuses.

“Isn’t it strange,” Fleischmann writes, “to grow up in a culture where your own experience is so completely erased that you don’t even realize you’re possible until your early twenties?”

Part of what makes Fleischmann such a compelling author is that they have certain obsessions that they return to again and again throughout the piece, albeit from different angles. We gain so much not only from what they learn about these obsessions, but from their interest in understanding what lies at the root of them. One such obsession is with ice; or more specifically, ice at the moment that it breaks.

“Ice,” Fleischmann writes, “is not a pellucid thing, but a disarray of fissures and air.”

As it turns out, this description, of a thing in beautiful disarray, is an apt one for many aspects of Fleischmann’s life; their friendships, many of which fall somewhere in a transient space between platonic and romantic; the various ways in which they inhabit different places or refuse the construct of static habitation; the way in which their body can be a site of both dysphoria and euphoria, but normally occupies a place somewhere in between.

T Fleischmann has lived many different experiences, and they are willing to let you see both those that work, and those that seem to fail. “Time” is a book that you should read if you aspire to be a writer, because it is a book that makes clear the fact that writing is entirely inseparable from living. It is also, though, a book that anyone in their twenties should read; or for that matter, anyone who is figuring out how to be a person at any stage of their life.

Dani Smotrich-Barr can be reached at dsmotrichbar@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply