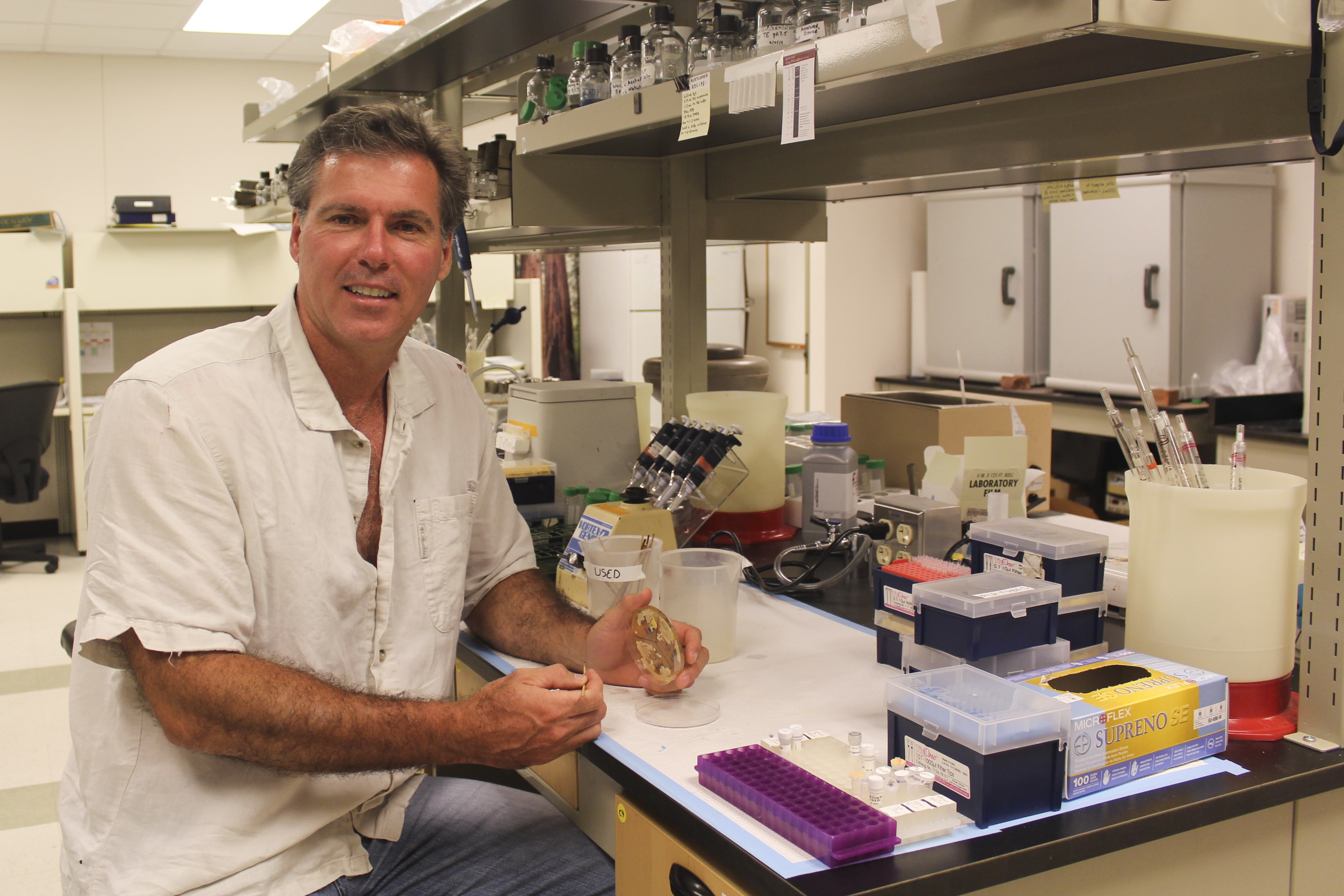

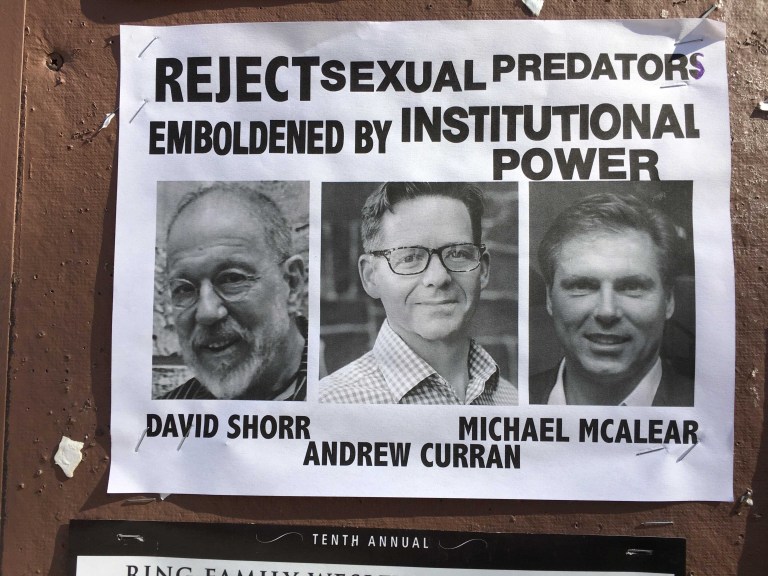

On May 8, Associate Professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry Michael McAlear filed a lawsuit against the University concerning student-made posters, circulated in November 2016, that implied McAlear, Professor of French Andrew Curran, and Professor of Art David Schorr are sexual predators. McAlear denies all claims of sexual misconduct in his suit against the University, saying that administrators have informed him that no allegations have ever been filed against him. His complaint, filed in the Middlesex Superior Court, alleges that the University failed to defend McAlear by not taking sufficient action to identify or discipline the students involved in the poster campaign, who remain anonymous to the public.

The posters at the heart of McAlear’s complaint were circulated as part of several protests and initiatives launched by students in reaction to apparent institutional failures regarding sexual assault and harassment, including the lack of transparency in the dismissal of former Associate Dean of Students Scott Backer, during the 2016-2017 school year. An allegation of sexual misconduct against Professor Curran was central to a lawsuit filed against the University by former Associate Professor of Classical Studies Lauren Caldwell, who alleged that she experienced repeated sexual harassment from Curran between 2012 and 2014—according to Inside Higher Ed, Caldwell settled with the University out of court. Professor Schorr is alleged to have made unwanted sexual advances towards male students in his classes prior to his death in 2018.

In the complaint, which was first amended on July 12, McAlear provides a timeline of events detailing a confrontation between himself and a group of protesting students that took place on Nov. 11, 2016, prior to the distribution of posters indicating McAlear is a sexual predator. McAlear had a contentious exchange with the students, who he says were calling members of faculty perpetrators and promoters of sexual violence.

“The plaintiff told the students that he thought their protest was over-the-line and slanderous,” the complaint reads.

McAlear believes that students called him a sexual predator due to the aforementioned confrontation. To his knowledge, he was first labeled as a sexual predator in an email sent by a student organizer to the Wes Student Union on Nov. 13, 2016, and then on posters beginning Nov. 16.

The complaint states that on Feb. 28, 2017, McAlear learned of more posters circulating with his name on them, and that an image of one of the posters had been uploaded to Wesleying. Additional posters continued to circulate in May 2017 and November 2017, McAlear alleges.

McAlear also describes an ongoing dialogue with former Provost Joyce Jacobsen, indicating that during the initial circulation of posters, Jacobsen and McAlear were in communication about uncovering the identities of the students who had created and hung them around campus. McAlear alleges that at least one student was eventually identified by the University, an allegation that the University does not deny in its July 11 motion to strike. McAlear further claims that Jacobsen later declared that no action would be taken against students found responsible for the distribution of the posters.

On April 27, 2018, McAlear says that he filed a complaint with the Faculty Rights and Responsibilities Committee against Jacobsen.

“Plaintiff’s complaint alleged that Jacobsen failed to protect and defend his rights as a tenured faculty member by not taking sufficient concerted action to identify or stop the persons who were conducting the degrading poster campaign,” McAlear’s case filing reads.

Additionally, McAlear claims that although President Michael Roth ’78 initially condemned the distribution of the posters and promised he would do everything he could to prevent them from being circulated, Roth later stated that he would not take action against any students found responsible.

McAlear’s original complaint, which has been twice amended, alleged breach of contract, breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing (resulting in mental and physical distress and reputational damage), recklessness, and promissory estoppel (in other words, that the denial of previously promised protection constitutes a legal infraction on the part of the University).

As compensation for the aforementioned violations, the suit demands an excess of $15,000, including interests and costs.

Under the count of breach of contract, the complaint posits the University is in violation of Section 3.1 of the Faculty Handbook, which establishes faculty members’ right to protection from the University.

“The right to abstain from performing acts and the right to be protected against actions that may be harmful to the health or emotional stability of the individual or that degrade the individual or infringe upon his/her personal dignity,” the Faculty Handbook reads. “This language is directed at all forms of personal harassment including the use or threat of physical violence and physical or nonphysical coercion.”

In his original complaint, McAlear claimed that as a result of the distributed posters, he experienced “severe emotional distress,” which he argued is protected against in the Faculty Handbook. McAlear claimed that the subsequent failure of the University to protect him constituted a breach of contract.

The University refutes this conclusion, arguing that employers can only be held liable for negligent emotional distress that occurs during the process of an employee’s termination, as established in Perodeau v. Hartford (2002). Since McAlear retains his employment status, the University argues that he is not entitled to damages. McAlear has since amended his complaint to remove the count of negligent emotional distress, as well as the count of negligence.

On July 12, McAlear amended his complaint to assert that the inflammatory language of the posters, specifically the use of the term “sexual predator,” constitutes defamation per se, in that it asserts that McAlear committed a crime involving moral turpitude, i.e. an act that is morally unscrupulous and intrinsically bad.

In their motion, the University contends that McAlear’s complaint does not provide proof for all four essential elements of defamation per se claim—a false statement of fact, publication or distribution of this statement, negligence or intentional deceit involved in the publication or distribution of this statement, and injury to reputation caused by this statement—and that McAlear cannot pursue a defamation claim against the University if he cannot name the person responsible for defaming him.

While the court will indeed be tasked with determining the presence of the first three elements, Connecticut law presumes injury to a person’s reputation in cases of defamation per se. As such, it is unlikely that McAlear will be required to prove special or actual damages. Additionally, the court must decide if McAlear’s defamation claim necessitates the identification of the perpetrator, and, more importantly, whether the University can be held liable for defamatory statements made by its students. In their motion, the University rejects the claim that they could be found vicariously liable for defamation, as McAlear does not provide proof that University employees had any involvement in the publication or circulation of the posters.

“There is not a single allegation that Wesleyan (or any of Wesleyan’s agents) made a false statement of fact regarding Plaintiff,” the motion asserts.

While the University’s response states that it considers all factual allegations to be true for the purposes of their motion, they have asked the court to strike all of McAlear’s legal claims on several different bases, as the University contests McAlear’s legal interpretation of the facts—asserting, for example, that McAlear does not provide any proof to support the allegation that the University acted with reckless indifference to his rights

“Wesleyan denies the allegations contained in Professor McAlear’s complaint and intends to vigorously defend itself,” University Director of Media & Public Relations Lauren Rubenstein wrote in an email to The Argus. “As is our policy, we will not be commenting further on this active litigation.”

A court date is scheduled for September 13, 2019.

Hannah Reale contributed reporting.

Emmy Hughes can be reached at ebhughes@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter at @spacelover20.

Erin Hussey can be reached at ehussey@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter at @e_riss.

Leave a Reply