Sara McCrea, Assistant Features Editor

Here at The Argus, we have been very excited about theses. In the few weeks since the seniors popped champagne on the Olin steps, we have featured exhibits, performances, and written projects from the class of 2019. It’s been thrilling to learn about what everyone has been working on and to see all their hard work pay off, and it’s also been nice to ask seniors about their theses without receiving groans in response.

All this thesis talk made me curious about the ghosts of theses and essays past, which haunt the University’s special collections. Yes, theses after 2007 are available on WesScholar, but what about the ones written before then, the ones set in typewriter ink? Another question occupied my mind as I walked toward the Special Collections reading room: Does the quality of one’s senior project correlate to the greatness of one’s future? Taking three of Wesleyan’s successful actor alumni who majored in theater as examples, I investigated.

c/o IMDb.com

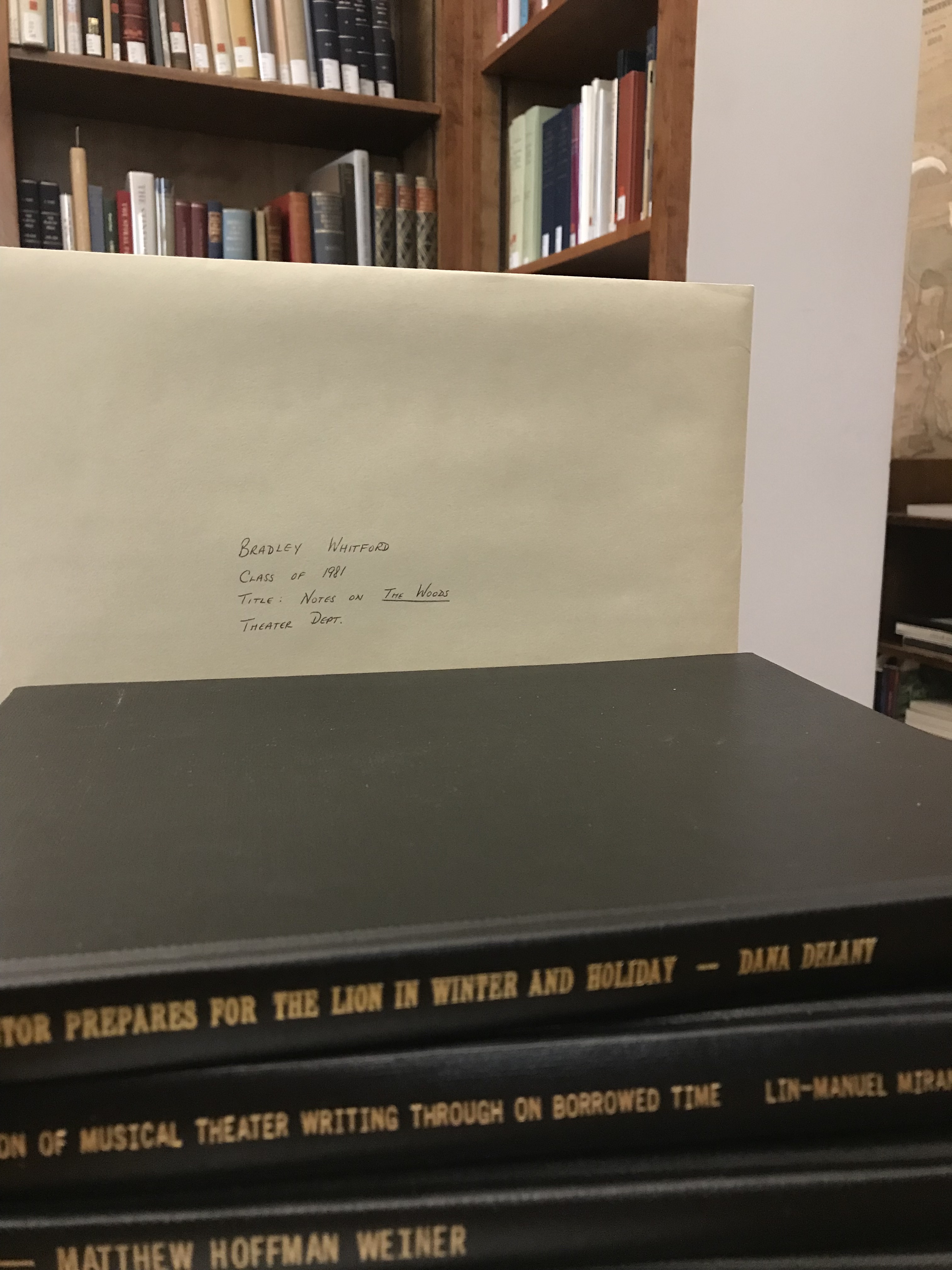

Bradley Whitford ’81:

Title: Notes on “The Woods”

You probably know Whitford as the Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman on “The West Wing,” or the donor on the plaque of “The West Wing” of the Usdan dining hall. Whitford, an actor and political activist, chose to write a senior essay in which he reflected on his Wesleyan performance in the play “The Woods,” by David Mamet, as well as his experience teaching a theater course as an Undergraduate Faculty Fellow. The written element of the project is a condensed version of his rehearsal journal in which he discusses his character choices, while also including some snide comments about his director, who was clearly not playing his part.

On his opening page, Whitford remarks, “When looking for something to perform as my senior thesis, my first concern was to find a capable director.” While the essay was centered on Whitford’s acting experience, he dedicated a large part of the piece to an exploration of the relationship between an actor and a director. It may not be too far a leap to suggest that a grudge prompted this emphasis.

Additionally, in his opening, Whitford evaluates his experience performing in over a dozen plays at Wesleyan, only about four of which, he claims, were exciting exercises in acting. Whitford noted he gained some valuable knowledge from these experiences.

“While the rest were worthwhile as raw experiences and as a chance to do some limited exploring, in general they have been rather frustrating, demeaning affairs,” he writes. “By the time my junior year came along, I had realized that one should chose [sic] their acting opportunities by director rather than role or play.”

As is made apparent throughout the essay, it seems that the greatest lesson Whitford learned throughout his time in “The Woods” was to not be dependent on a director to go the extra mile, or even to complete the mile.

“An actor is at the mercy, to a large extent, of the director’s ideas (or lack of them),” Whitford writes later in the essay.

In addition to his rumination on the role of a director, Whitford explores his character quite thoroughly, scene by scene, and imparts wisdom along the way. In his conclusion, Whitford leaves himself and his reader with three pieces of useful advice. The advice is in reference to the acting practice, but it could also very well apply to both thesis writing and life in general:

“Simplify—Be as simple as possible. Less is more. Trust the script. Trust the situation. Don’t ‘indicate.’

Find the dynamics—See the shape. See where and how the piece moves. See where you have to be and when you have to be there.

Work. Work. Work.—Don’t kid yourself.”

c/o tvguide.com

Dana Delany ’78:

Title: An Actor Prepares for “The Lion in Winter” and “Holiday”

You are probably familiar with this Emmy-winning actress from her work on “Desperate Housewives,” “Body of Proof,” and “Hand of God.” At Wesleyan, Delany majored in theater and spent the summer before her senior year working in summer stock productions in Augusta, Michigan. She wrote a full-length thesis reflecting on her rehearsal processes for James Goldman’s “The Lion in Winter,” in which she played Alais Capet, and Phillip Barry’s “Holiday,” in which she played Julia Seton.

“Acting is a personal art which never stops growing and developing,” reads the opening line of Delany’s thesis. Throughout the thesis, she takes old acting adages (“There are no small parts, only small actors”) and deconstructs them through a detailed explanation of her rehearsal process. She also weaves academic texts on the practice of acting throughout, applying the theoretical frameworks to her roles.

For each role, Delany wrote an in-depth character sketch in which she included thorough backstories and meditations on the character’s motivations throughout the play. The sketches contain scene-by-scene explications of the setting, the circumstances, the objectives, the beats (pauses), and how the rehearsals went.

Like Whitford, Delany appears to have been frustrated with her direction, journaling that someone named Harvey, the director of “The Lion in Winter,” had a “directional tantrum.”

“[W]e were told we would stay all night until we got it right,” Delany wrote. “Harvey has alienated his entire cast. You do not bully people into creativity.”

Still, Delany found joy in the rehearsal process.

“Here at Wesleyan, where the average run of a play is three nights, it is the rehearsal stage which is important to me. It is a period of growth and discovery,” she wrote.

In closing, Delany writes:

“As an actor I would attempt anything, as long as I could base it on my personal TRUTH.

My final point is, ‘The play’s the thing.’

… ACTING IS DOING.”

c/o variety.com

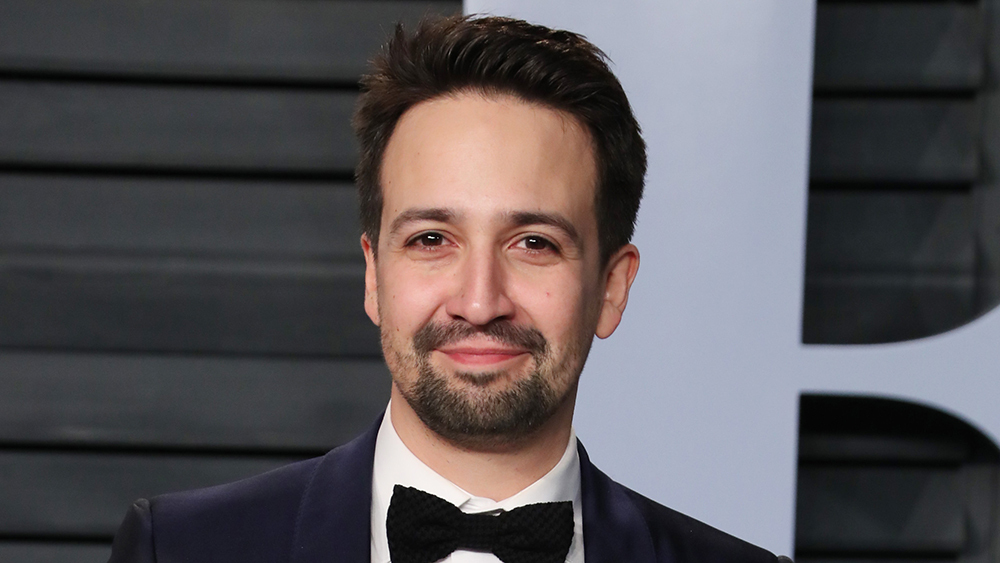

Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02:

Title: An Examination of Musical Theater Writing Through “On Borrowed Time”

Wesleyan poster child Lin-Manuel Miranda was sitting in his room at the University and watching Murray Horowitz—an acclaimed lyricist, NPR broadcaster, and writer whom Miranda greatly admired—shake his head in disappointment as he listened to one of Miranda’s new songs. Horwitz was the father of Miranda’s housemate, Alex Horwitz, and had agreed to give Miranda some advice on his originals.

“These words would be fine if you were writing a rock song. You can have loose, lazy rhymes in rock, pop, do whatever you want. But this is musical theater, Your lyrics must be airtight,” Miranda recalled Horwitz saying.

Before he left for brunch, Horwitz delivered one final piece of advice to the Wesleyan student, which Miranda also included on the first page of his thesis:

“Lin, buy a rhyming dictionary,” Horwitz said. “They’re a great resource. And get ‘Lyrics for Several Occasions’ by Ira Gershwin. Gershwin is a motherfucker.”

Miranda describes “Lyrics for Several Occasions” as a mix of style: part autobiography, part critique, part how-to manual. In his thesis, Miranda took a similar approach to Delany, weaving personal anecdotes through analysis and original content.

Miranda’s thesis set out to explore a question which many have since asked about his work following his time at Wesleyan: What makes a lyric work? The first part of the thesis examined the art of musical theater lyric writing through the writings of legends Ira Gershwin, Oscar Hammerstein II, and Alan Jay Lerner. Each of these writers came from (and formed) different traditions, but Miranda approaches the work of each through examining the lyrics themselves along with the lyricists’ writings on their art.

The second part of Miranda’s thesis was not “In the Heights,” as some assume, but an original musical called “On Borrowed Time,” which he put up as a workshop during his senior year. He also included excerpts from the play in his written thesis on lyric writing. “On Borrowed Time” can best be described as a time-travel romance, complete with a pretty explicit sex scene between two teenagers as its opening number. In an interview with Howard Sherman, Miranda talked about the four musicals he wrote throughout his time at Wes.

“Only one of them was ‘In The Heights,’” he said. “I wrote another one called ‘On Borrowed Time,’ which was my senior thesis, which if I have my way you’ll never hear.”

In the conclusion of the analytical portion of his thesis, Miranda already seemed to be self-aware.

“I am learning. With every song I write, I am learning.”

Sara McCrea can be reached at smccrea@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @sara_mccrea.