In “Cardboard Piano,” Love Persists Even If Forgiveness Cannot

Love has a funny way of growing in the places where it’s most dangerous, across cultures that struggle to co-exist, between bodies who have been told that attraction between them is impossible. And yet, love exists despite the boundaries that tear us apart. That’s a fact that audiences get to mourn and revel in while watching Hansol Jung’s absorbing play “Cardboard Piano” (running May 2-4 in the Alpha Delt Green Room), through a love story that cannot be extracted from the chaotic world it takes place in.

The play follows Chris (Michayla Robertson-Pine ’22), a young white teenager and daughter of American evangelical missionaries, after being transplanted into the war-torn Uganda of 1999. On New Year’s Eve before the new millennium, she arranges a secret meeting in her parents’ church with her lover Adiel (Shanna Henry Phillips ’22), a local Ugandan teenager. What at first appears to be a sensual rendezvous between adolescent girlfriends, complete with candles and Oreos, becomes something much more dangerous and sacred: They’re actually together to get married. Even though the ceremony is only symbolic, with only a tape recorder as a witness, they’re consecrating their love the only way they know how. In a moment of intimacy, they dance with each other while singing “Unchained Melody,” desperately holding onto each other as if their lives depended on it. And maybe their lives do depend on each other. For a moment, we’re invited to envision a world where this kind of love is possible.

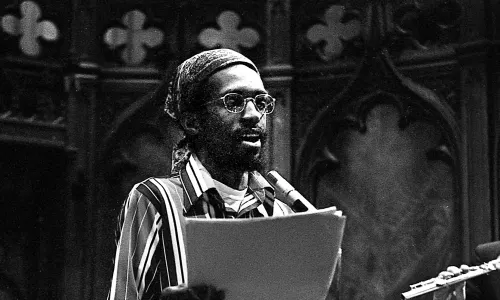

But the desperation that brings them together is also what tears them apart. The love between Adiel and Chris—between two young women, across two nationalities and races—is so powerful because, to the outside world, it should not exist. This chaotic world influenced by Ugandan and American politics crashes into the church abruptly and violently when the child soldier Pika (Fitzroy Pablo Wickham ’21) hides away from his ruthless overseer (Cameron Smith ’21) and thus interrupts the marriage ceremony. Brandishing a gun and bleeding from a cut-off ear, Pika is a direct threat to Adiel’s and Chris’ lives. But under the innocent distress of Wickham’s performance, we also see that he’s just a vulnerable kid looking to be saved.

As the three face off with each other, they’re immediately confronted by ethical questions and high stakes. Can Pika escape the dangerous cycle of violence he’s a part of and be absolved of the atrocities he’s committed as a soldier? Can the three of them find solidarity in each other despite the chasms of privilege that sit between them? The most pressing question is whether Chris and Adiel are obligated to stay with their homophobic countries or families, or if breaking free from this oppression is even achievable. Hoping to run away, Chris frantically tells Adiel, “I have to put my God on the altar, you have to put your country on the altar, and say, none of these things matter more to us than each other.”

These difficult questions of forgiveness and morality are what inspired director Eliza Wilkins ’19 to take on this challenging show. Discovering the play while working at Connecticut’s Eugene O’Neill Theater Center last summer, she thought that the play’s global perspective distinguished it from other conversations about Christianity and homosexuality.

“Uganda has a history of very homophobic roots,” she stated. “Part of that is due to the presence of evangelical missionaries in Uganda that have introduced this concept of morality of whether or not you’re straight or not…. I think this puts Chris in a really unique position where she’s both oppressed and implicated in the homophobia she feels and experiences.”

One of the most exciting things about the play is its implication of white American audiences in Ugandan politics, revealing how Americans are inevitably tied to the violence occurring across the world while trying to offer salvation through religion. Wilkins traveled to the International House of Prayer in Kansas City, Mo., to get a first-hand account of evangelical language, space, and practices. Problematizing white LGBTQ+ women’s positionality, in terms of both their privileges and oppression, is one of Wilkins’ main goals in putting up this work.

“The best thing I can say is we often assume the position of Chris, like ‘I wanna fix things, I wanna help,” she revealed. “Missionaries often assume [that position], and it’s a problem. I don’t have a solution, but I know that there’s something wrong with inserting yourself in a place and expecting them to follow your rules.”

Part of this problematizing project included being cognizant of her own privileges as a white director to a primarily black cast. Wilkins collaborated with Bofta Leakemariam ’21, an assistant director, to ensure that an international Black perspective was being recognized. Working with a large production team, she spent the first month of the semester doing extensive dramaturgy and facilitating discussions about the play’s setting. This included bringing Hansol Jung and O’Neill Theater Literary Manager Lexy Leuszler onto campus for a Q&A about the play and new work development. And although Wilkins acknowledges the historical context of utilizing Black trauma for a white director’s gain, she views theater as the critical engagement of identities that are not your own.

“I think honestly it’s a really productive exercise to try to overcome that history in the smallest possible ways that I can, as just one human with all my limitations,” she said. “I think part of it is just recognizing my position in this…especially because this play is written by a South Korean [playwright] about Uganda! So I’m like, ‘Yeah, I’m gonna go through this exercise, yeah I’m going to stretch myself’ …. There’s a distance I will always be from this play that I feel very close to.”

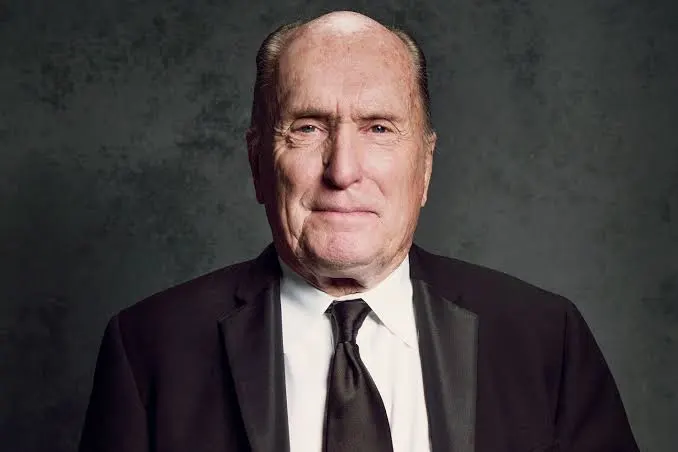

This emotional act of bridging distances, of longing to connect with others despite the fractured influence of history, is the source of the empathy written directly into “Cardboard Piano.” As the violence surrounding Chris, Adiel, and Pika escalates, they’re forced to make devastating decisions that impact the course of their lives. These decisions come back to haunt the church in the second act, which takes place fourteen years later and has the actors playing different roles. The childish Pika has changed his name and transformed himself into Paul (now played by Smith), a preacher who has used Christianity to forgive himself and advocates for others to do the same. His humorous and resourceful wife Ruth (Henry Phillips) is asking Paul to extend the same generosity to Frances (Wickham), whose homosexuality is leading to both marginalization from the town and self-harm. But when Chris (still played by Pine) arrives back to the church in order to bury the ashes of her father, the consequences of that fateful New Year’s Eve come to light. The question of who can be forgiven and when is put into a furious scrutiny that eventually bleeds into heartbreak.

The ensemble of “Cardboard Piano” gracefully maneuvers its double-casting, embodying the switch from teenage innocence to adult maturity while still echoing reflections of their former selves. The absence and burden of those fourteen years weigh heavily on the characters, as they learn to live with the choices they’ve made and we see how they’ve shaped the people they have become. Similar to the film “Moonlight,” which also interspersed its narrative of queer blackness with huge time jumps, we might view “Cardboard Piano” as portraying what Professor of English, African, and Afro-American studies at Brandeis University Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman calls the “black ecstatic,” a work of art that “punctuates its chronicle of racial suffering and masculine malaise with portrayals of rapturous joy.” By withdrawing from a mere recreation of black suffering and filling her play with pathos, romantic love, and a surprising amount of humor, Jung has created a portrayal of life that celebrates love specifically in the places of trauma.

“I want people, especially queer women, to feel empowered coming away from this piece, because they’ve seen a representation of a lesbian that’s complicated and problematic and challenging, that they’ve aligned with and that they’ve hurt with” Wilkins said. “Even though I know this is full of trauma…I think there’s so much exciting me as a gay woman, to see two lesbians dance together in a wedding ceremony onstage. It means more to me than I can express in words.”

Maybe words cannot express a lesbian love put under so much pressure but still so ecstatically alive and present. Some of the most powerful moments of the show happen outside Jung’s writing, when Wilkins’s direction shines through and Adiel and Chris are allowed to simply caress, touch, and kiss. For a moment, watching Adiel and Chris, we can finally imagine a world where their love could thrive and live in it, if just for a moment.

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply