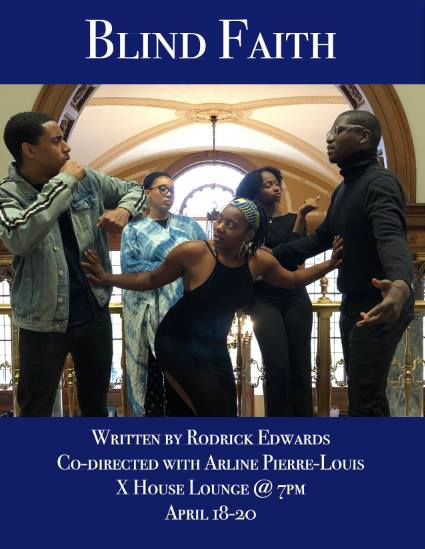

When was the last time you’ve spoken completely honestly to your family? Talking to your parents and siblings—directly, unabashedly, even brutally—is something that most people rarely have the courage to do. Rodrick Edwards ’19’s new play “Blind Faith” (running April 18 to 20 in the Malcolm X House basement) recognizes this fact and allows viewers to witness a family struggling to air their grievances and reconnect with each other in a space that seems only tangential to reality. It can be thrilling to watch as family members finally express their feelings that they couldn’t in “real life.” But it can be just as painful of an experience to watch, too.

The opening scene of the show is a conjuring of sorts. The character of Granny (Dache Rogers ’18) hums by herself, illuminated in a brilliant blue light, leaning back and forth in a rocking chair and tapping her leg. Soon a chorus of singers (Samia Dudley ’20, Jadan Villaruel ’20, Jay Reyes ’22, and Dachelle Washington ’22) joins her in harmony, singing an a cappella, gospel-tinged song which states:

“My mama told me ‘bout them / Troubled waters / She told me baby / Don’t get too close.”

It’s both a requiem for past actions and also an invitation for the audience to reconsider the lessons they internalized as children. The following scene retains the same sense of ritual and communion, even if what we’re watching seems just like an ordinary family dinner. Big Brother (Charles Bonar ’19) has returned from a long absence to see his family for the first time in many years. Along with him and Granny are the rambunctious Lil Brother (Hezkiel Berhanu ’22), who won’t talk about the cuts on his wrists, Sister (Inayah Bashir ’20), who seems a little detached from the proceedings, and the frustrated, authoritative Mama (Michelle Nivar ’20), who only wants to keep the peace.

The conjuring of ghostly presences in the play’s opening music mirrors what happens in the dining room: The family, long separated by death and emotional distancing, has been brought together by some supernatural powers to finally confront what has never been confronted.

While “Blind Faith” seeks to unravel its characters and reveal their traumas, it’s also a tender portrait of a family that would be recognizable to many. Lil Brother and Big Brother still argue with each other like teenagers (humorously over a stuffed bunny named “Pinky”); Sister defuses the tension at dinner with lines such as “Can you pass the rolls?”; Mama repeats the phrase “I love my children” to herself to keep herself from snapping at them. These familial dynamics reveal the humor and joy in these familial arguments, even as they hint at more disturbing forces moving below the surface.

When these past traumas finally cannot be contained anymore, they spill out into searing speeches, forcing the other family members to witness their relatives’ pain. The ensemble of the show performs these speeches with a blunt reality that makes their words feel like a release of a long-held secret. Bashir portrays Sister with a furious intensity, especially when addressing the way in which a stroke caused everyone in her life to treat her differently. But with Berhanu’s sullen expressions, it’s clear that Lil Brother’s sense of not belonging is just as acute, as it’s revealed how the burden of taking care of his sister led to his own self-destructive actions. The relationship between Sister and Lil Brother shows a troubling contradiction: How can two people both feel like they were the ones who suffered at the hands of the other? Who’s fault is it? While blame initially switches between the brother and sister, eventually it’s directed towards themselves, their mother, and eventually at God.

These dilemmas carry a personal weight for Edwards, as he calls the play an “auto-ethnography of my family and myself.” Edwards drew from his own relationship to his sister and mother (who is a preacher) to create the story.

“From my perspective growing up it was just never discussed,” Edwards said, speaking of Sister’s existential, Job-like reckoning of the pain God has given her. “It was just always, ‘Have faith.’ And I’m just like, that’s a lot easier said than done. I wanted people to see the difficulty in staying in faith.”

While religion seems to be the guiding example of how a family can be divided in the show, there are plenty of other ways “Blind Faith” invites its audiences to connect with the characters, whether it’s through the burdens of being a sibling, the question of who can claim to be impacted by disability, and whether identities can be carved out independent of childhood backgrounds. Although the play might seem uniquely personal to Edwards, he hopes that anyone could connect to the story.

“I wrote it very much in the language of a Southern low-income black family…and those vibes are still there,” he stated. “But [I enjoy] finding that way for different people to connect with it. With all the different themes in the play, I purposefully tried to make the characters not so specific, [like] it could only fit in one audience, so that people could try to find their way in.”

Indeed, one of the interesting things about “Blind Faith” as a piece of dramatic writing is its structural openness: There are no names or racial identities attached to the characters, and the show has minimal stage directions. On the page, the dialogue’s poetic enjambment resembles the work of Suzan-Lori Parks, debbie tucker green, or Tarell Alvin McCraney, contemporary black playwrights whose theatrical worlds also are formally abstract and not attached to a specific time and place. But under the direction of Arline Pierre-Louis ’19, Edwards’s writing is transformed into a world that is tangible and real. With a realistic set interspersed with plants and prayer candles (designed by Camille Balicki ’21), audience members always feel like what they are watching, even with the show’s supernatural elements, is genuinely happening. If some of the lyrical quality of Edwards’s language doesn’t translate as directly into this production, what takes its place is the wrenching quality of being trapped in a room with a broken family. Edwards says he really appreciated this different take on his play, seeing another person’s vision come to life. The poetic elements of the writing still shine through in the musical interludes (directed by Langston Lynch ’20, Alana Morrison [TCEX], and Edwards himself) which push the dialogue scenes into a more mystical, surreal place.

As his final theater project at Wesleyan, and the opening show of the SHADES Theater Festival, “Blind Faith” represents the culmination of Edwards’s work to make the theater community at Wesleyan more inclusive. As one of the leading members of the SHADES Theater Collective (a group creating theater by and for students of color), he’s personally seen the evolution of Wesleyan theater during his four years here. While he feels like there has definitely been a shift in conversations about theater on campus, he still sees more possibilities for improvement.

“I feel like where I want SHADES to go is to continue making theater for students of color on this campus so they can feel comfortable to share their stories that are not commonly seen on stage,” Edwards commented. “I would love it if SHADES and [Second Stage] could collaborate…so that we’re not in opposition, but so that we’re just helping each other, learning from each other.”

“Blind Faith” seems to put this creative collaboration in action, creating a theatrical world that both speaks to Edwards’s personal experiences, and still opens up a world for people to read themselves into. As the family in “Blind Faith” confronts their shared pain, they discover that much of their trauma stems from recognizing themselves in each other. It might have taken many tragedies for family in “Blind Faith” to finally reconnect with each other, but perhaps the act of watching “Blind Faith” in the theater is itself a form of connection—to a very personal history, to a better understanding of yourself, to the other people you’re watching in the room. Edwards understands that the questions and pain brought up in “Blind Faith” may never be resolved. But it’s the act of witnessing other people that have the power to transform, if not heal, that is what allows the audience to come to terms with this lack of resolution.

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply