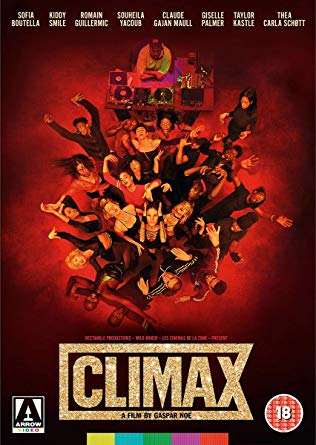

Gaspar Noé’s newest film “Climax,” winner of the 2018 Art Cinema award at Cannes and released in the United States this month, is at once unlike any movie ever made, and all too familiar for Noé’s filmography. The film chronicles a French dance troupe’s breakdown into madness after they are unknowingly drugged with LSD during a party after one of their rehearsals. The story is loosely based on a real event that took place in the early ’90s in France but dramatizes its surreal qualities in typical Noéan fashion. For the polarizing French-Algerian art house filmmaker, whose career has been marred by controversy, this film has been his most critically successful, heralded as a masterpiece.

Noé has made a career on the profane, absurd, and disturbing: cinema as ecstasy. One of his first major films, “Irreversible,” was lambasted for its brutal portrayal of violence, a 10-minute-long rape scene, and homophobia. A later film, “Love,” experimented with an erotic drama in 3D that critics similarly criticized for its excessive full frontal nudity and glorification of male genitalia.

Noé’s evident inclination toward provoking audiences along with the blasé responses he’s given in response to the pushback that his films receive have put him in a camp with other controversial contemporaries such as Lars Von Trier and Harmony Korine.

However, while “Climax” is certainly jarring, it is closer in essence to his previous 2015 film “Enter the Void,” a more cerebral tour into life after death. If anything, “Climax” can be seen as a continuation of the existential themes and psychedelic style explored in “Enter the Void.”

“Climax” is arguably Noé’s first movie where the extreme aesthetics seem to be in purpose of some higher project than just shock value or an ecstatic thrill. It’s a multifaceted meditation on cultures of hedonism, presenting the extreme pleasures it can produce as well as the hellish nightmare it inevitably unravels into. The film opens with a recording of dance troupe members, composed of a diversity of ethnicities and sexual orientations, discussing what dance means to them, its total sensory experience, as well as their relationship to France. The recording plays on an old VCR TV and is surrounded by books on psychology and philosophy. The whole composition of this opening recording gives the impression that the dancers are participating in a social experiment, even though it’s never exactly explained what the dance troupe is engaged in.

Interrupted by intermediary title sequences scattered across the film, rather than just at the beginning to introduce plot shifts, the film then switches to an almost 10-minute single-shot dance scene, played to hypnotic electronic music. The dance sequence is the high point of the film, an all-immersive joyride into the carnal pleasures of sensory experience. The role of the camera in the scene is also very telling for the film. The single shot, weaving inside and outside of the performance, becomes a part of the choreography of the dance routine that it’s shooting. The intertwining of dance and film in the scene could be seen as symbolic of Noé’s approach to film in general: suggesting that film at its essence is just like dance, a visual exploration of our hedonistic and sensual tendencies. Once the performance ends, the film quickly transitions into presenting the relationships between the individual dancers. While they are evidently a tight-knit group, they interact somewhat superficially, gossip behind one another’s backs about who has slept with whom, and manipulate each other for personal gain. At a certain point during the party, everyone starts to realize that the punch had been spiked and that they’re all tripping on acid. The group devolves into chaos as their basest behaviors and instincts come out. After starting at such an emotional high, the film turns into one collective bad trip. As characters each lose their minds, the camera doesn’t visually present what they are experiencing psychologically, but rather observes them from a distance. This lack of access to the characters’ interiorities, on the one hand, creates tension for the audience but is also one of the failings of the film. There are hardly any real characters in “Climax.” The movie is composed of caricatures of types of people. And the types that they’re meant to show aren’t particularly flattering. We only see the petty, vain, selfish, or unflinchingly evil sides of the dancers.

Made by a filmmaker whose works have daringly explored psychological, sexual, and philosophical themes, “Climax” could be read as Noé’s most political work yet. The characters in the opening sequence talk about French identity, and how it doesn’t mean anything anymore. This existential predicament hangs over the film as the madness that unfurls all happens under a neon-colored French flag hanging on the back wall of the dance studio. While the film was shot back in 2017, Noé captures a sense of cultural precarity in France that, in light of the months-long yellow jacket protests still raging today, was highly prescient, as its political system seems to be unraveling once again.

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lwgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply