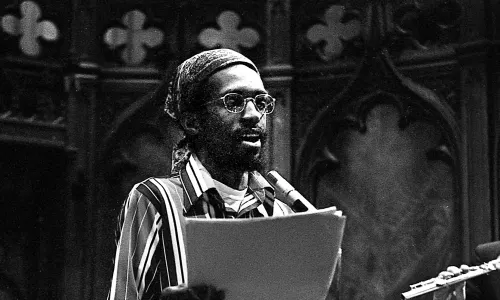

Author Terry Tempest Williams Discusses Relationship Between Humans and Environment

Renowned author and environmental activist Terry Tempest Williams spoke at Memorial Chapel this past Friday at an event sponsored by the College of the Environment, reading from her work and discussing her career and thoughts on environmentalism. Tempest Williams has written a number of books, essays, and poetry collections, and her work has taken her around the country and the world. One of her earliest and most well-known works, “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place,” blends memoir and natural history, juxtaposing a personal trauma (Tempest Williams’ mother’s battle with breast cancer) with an environmental trauma (the flooding of a local bird refuge). “Refuge” addresses topics as diverse as Tempest Williams’ family history of cancer, her relationship with religion, the rising water levels of Utah’s Great Salt Lake, and the American government’s nuclear testing in the Southwest. This multi-facetedness is characteristic of Tempest William’s work, which often relates to subjects such as ecology, public health, preservation of public land, as well as our relationship as humans to the rest of the natural world.

Tempest Williams’ experience with the environment is not limited to writing; among other positions she has worked as a curator at the Utah Museum of Natural History, served as a team member on the President’s Council for Sustainable Development, and co-founded the Environmental Humanities program at the University of Utah. Currently, Tempest Williams is the writer-in-residence at the Harvard Divinity School, where she is studying and writing about the spiritual implications of climate change and environmental degradation. Over the course of her talk at Wesleyan, Tempest Williams shared a variety of stories about the importance of closely studying nature and the environment, such as her co-founding of the University of Utah’s acclaimed Environmental Humanities program.

“Long story short, we started an environmental humanities graduate program, the first in the country,” Tempest Williams said. “And we focused on how the humanities, the arts, and the sciences could help us think about what it was to be human.”

The interdisciplinary master’s program, which Tempest Williams helped found in 2003 and also taught in, helped students analyze environmental issues through writing and other art forms. During her time at the University of Utah, Tempest Williams was known for her hands-on teaching, often taking students into the deserts or mountains to study the environment firsthand. However, Tempest Williams left the program in 2016 after clashing with the school’s administration over her focus on field-based over classroom-focused teaching. Many of her supporters believed that the administrative pressure on Tempest Williams was related to discomfort over her environmental activism, and Tempest Williams herself seemed to confirm this theory, explaining that her departure occurred soon after she and her husband purchased an oil and gas lease as an act of protest.

“We did purchase 1,120 acres,” Tempest Williams said. The purchase was meant both to prevent drilling from occurring on that parcel of land and to call attention to federal policies allowing for excessive development of public lands. “Two weeks later, the new dean of the University of Utah called me in, with a University of Utah attorney, and told me, ‘Thank you for your service. You will no longer be working here.’”

Many of Tempest Williams’ environmental stories ended on a more positive note. One such story, originally told to Tempest Williams by her friend, restoration ecologist Sue Beatty, deals with the successful restoration of Yosemite National Park’s famous Mariposa Grove. As Beatty was walking among the ancient sequoias of Mariposa Grove one day, she was hit by a sudden inexplicable sense that something was wrong with the trees.

“She kept hearing the same thing,” Tempest Williams said. “We are suffering. Can you hear us? We are dying…. And she thought, ‘What on earth, you know, this can’t be possible.’ And she continued on her way.”

Over the next few days, however, Beatty’s unease persisted. Concerned that there might actually be something wrong with the trees, Beatty and her team conducted a comprehensive study of the grove’s health the next week and was alarmed to find that her suspicions were correct.

“What they found after that comprehensive study was that the trees were suffering, that they were dying,” Tempest Williams said. “Millions of tourists [were] tamping down their roots. Roads too close [were] blocking their root system.”

Beatty, along with the park’s leadership, created a multi-step proposal for restoring Mariposa Grove to full health, which involved temporarily closing the area to visitors.

“The plan that she laid out was [Mariposa Grove] can no longer be a place of entertainment and recreation. It must become a place of restoration, of reverence and reflection…,” Tempest Williams said. “And so for three years, they closed the Mariposa Grove, and the trees rested.”

As part of the restoration project, which was implemented starting in 2015, several waterways and wetland areas within the grove were restored, miles of pavement were removed, and trails were rerouted to avoid sensitive habitats. Tempest Williams cited this success story as an example of the importance of paying close attention to one’s surroundings, as Beatty did when she guessed something was wrong with the trees.

“I think about…the qualities most needed in this epoch now being called the Anthropocene, where the price of our species registers as a geological force.” Tempest Williams said. “One of the first qualities you might seek to cultivate is how to listen.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

She is far too focused on women’s issues