Ginger Hollander, Photo Editor

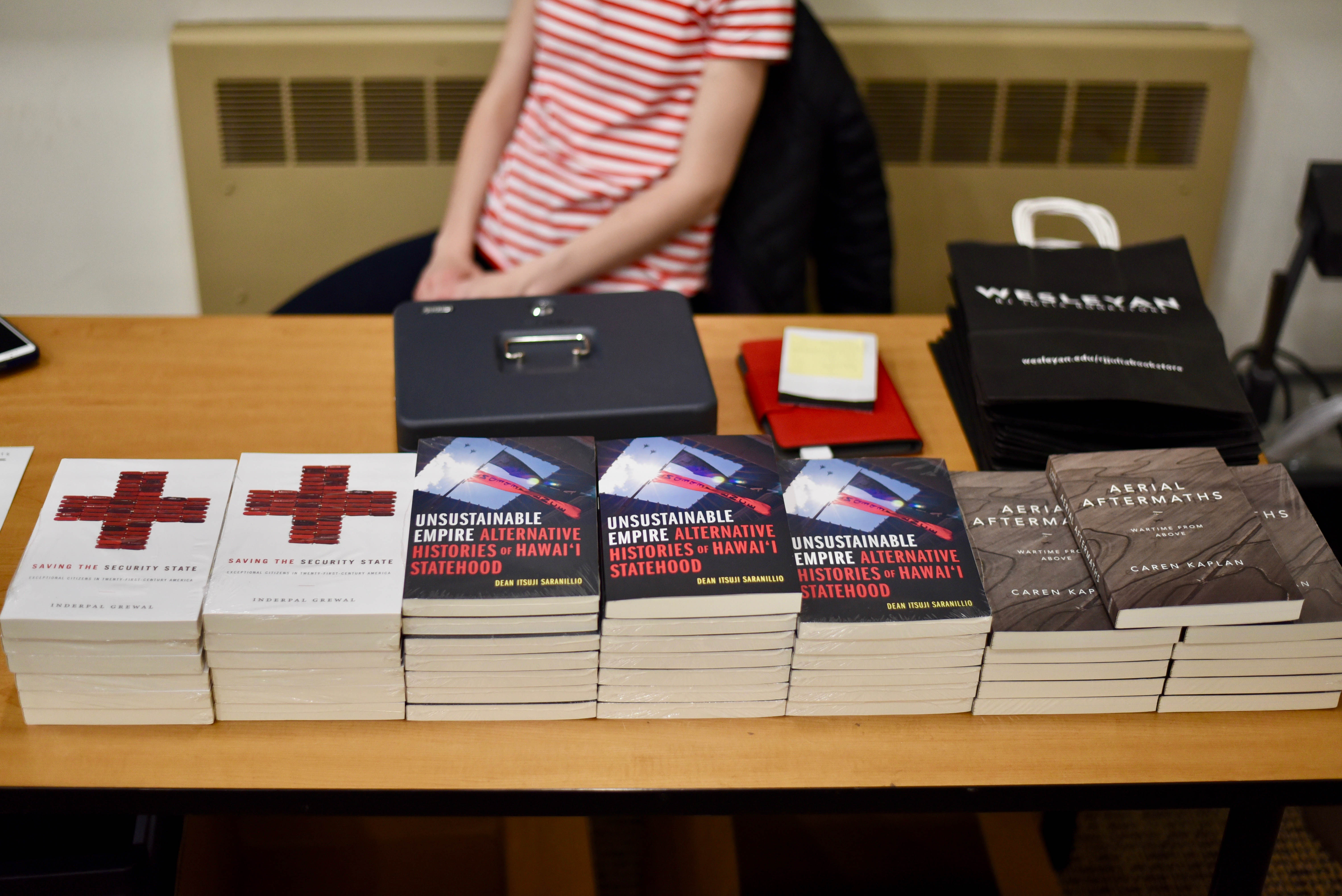

Last Thursday, students and faculty came together in Judd Hall to listen to a panel hosted by the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program. The panel, titled “Transnational Feminist Practices Against War,” featured Inderpal Grewal, Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Yale University, and Caren Kaplan, Professor of American Studies at University of California, Davis. Wesleyan’s own Professor Abigail Boggs moderated the panel.

In the last two years, both Grewal and Kaplan have released books and manuscripts that analyze war and war practices from a transnational feminist lens. Transnational feminism, similarly to intersectional feminism, takes into account identities across nationality, gender, and class, within the context of modern day imperialism and colonialism. It complicates the narrative around what it means to be a feminist, specifically pushing back against the traditionally white, western models that have been employed by scholars within the field. As explained by the event description, Grewal and Kaplan employ transnational feminist analyses in order to understand “militarization and securitization as intrinsic to daily life” in an “era of endless war.”

Ginger Hollander, Photo Editor

Grewal’s book “Saving the Security State: Exceptional Citizens in Twenty-First Century America,” published by Duke University Press in 2017, discusses the militarization of daily life within what she calls the “U.S. neoliberal empire.”

“This book is about the way in which the United States empire produces subjects who engage with the world in different sorts of ways.” Grewal said. “What is that imperial engagement with the world that is feminized, produced, rewarded, widespread.”

Her book discusses two different sides of the United States empire: one being the surveillance state, and the other looking at how Americans interact with travel and humanitarianism.

“I look at two modalities of empire, one being participation in the security state.” Grewal said. “That can be women in the CIA, or mothers who surveil their children and neighborhoods. I look at the way women are being captured by the surveillance state, and then I look at how people are captured by a very masculinist notion of travel and humanitarianism. That can be masculinized, but it also becomes how people start to picture a ‘Good American,’ this idea that Americans help the world and that they are not part of an empire that is lethal and has consequences on the world. I’m very interested in the ways in which the empire does this myth-making about itself.”

Kaplan’s most recent book, “Aerial Aftermaths: Wartime from Above,” also from Duke University Press, discusses the cultural history of drones in our society and how aerial views are so closely interlinked with war-making.

“Aerial Aftermaths starts in the 18th century with the first balloon flights and the first opportunity people had to actually look at the earth from the air in an embodied way,” Kaplan said. “I move into early aviation and World War I, particularly images of Iraq from the air during World War I. I end with drone stuff, which I’m very interested in and currently writing more about.”

Ginger Hollander, Photo Editor

Both Grewal and Kaplan emphasized how they bring feminist theory into their current studies of the security state and of warfare. For Grewal, she uses her past history of studying South Asia as a jumping point.

“The post-colonial theory lens gives me a way to think about the U.S. as both exceptional and unexceptional,” Grewal explained. I’m always thinking about South Asia and colonialism and writing about the American empire from that viewpoint, even if I’m not writing about South Asia. This is how I bring post-colonial feminist theory into whatever I’m studying.”

For Kaplan, the journey was a little more roundabout.

“I felt very stymied by only writing, so the thought of being able to create multi-media projects with a lot of imagery really spoke to me,” she noted. “It didn’t help me with the obligation I was under to produce another monograph, but I did it anyway. I was studying warfare and the history of military technologies that intersect with the history of cartography, a strong area of interest of mine. Aerial Aftermaths really took a long time because it took me a while to re-tool. I find that aerial imagery is very closely connected to the history of colonialism and imperialism and a lot of things I was already working on in the context of feminist studies. I feel that I bring things that I learned from feminist study into the study of digital culture in relation to military technology.”

Kaplan and Grewal have a long and storied relationship, both personally and professionally. The two met a number of times through mutual colleagues before they really got close.

“I had been hearing about this Inderpal Grewal, and how smart she was, and how I would really like her, and how we should meet,” Kaplan said. “She gave a talk at Berkeley, and I was like, wow, she’s really smart and cool. We had friends in common, and there was this intellectual community that was forming that was larger than us.”

The two truly got to know each other when Kaplan was at Georgetown a few years later.

“I was working in the English department, but I had never taken an English class before in my life,” Kaplan explained. “I was feeling pretty nervous and insecure, and I just wasn’t feeling quite at home. Grewal was in the area at the time as well,” Kaplan laughed, “and we found each other like two rats on a sinking ship.”

In the early ’90s, despite teaching at separate universities, the pair worked on their first manuscript together, titled “Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices.” When they both made it to California, they were teaching Intro-level Women’s studies classes at their respective schools and realized that the existing textbooks provided a faulty intellectual foundation for students. They started making alternative course packets and sharing them with each other.

Grewal said that a big reason why it was important for them to work on this textbook was because it questioned the existing way that Women’s and Feminist studies classes were taught.

“We always used to teach Women’s Studies in terms of the waves of feminist movements. Coming from South Asia and doing work on South Asia, I felt that the ‘wave’ structure just didn’t really make sense to many of our students who felt alienated from Women and Gender studies and who couldn’t identify with the major,” Grewal explained. “What I was seeing was a diversity of students for whom this ‘wave’ mentality made very little sense…So we took what we might call an ‘intersectional’ approach, but we really didn’t think about it that way at the time. Colonialism produced different kinds of bodies in Africa and other colonized spaces. Even in areas outside of western colonization, such as China, gender and bodies were articulated and seen in very different types of ways. So in our book, we tried to bring to students this idea that there really is no stable historical idea of what being a woman or of what gender means.”

The end result was a textbook titled, “Gender in the Transnational World: Introduction to Women’s Studies.” Kaplan said that she was initially a little nervous to do the textbook. But she realized that, due to her lighter workload than those of professors at other schools, she was in a privileged position to use her time to improve the teaching abilities and class quality at other schools, even if it didn’t necessarily benefit herself at Berkeley at that time.

After the panel, students and faculty alike asked the panelists questions. Kaplan was actually Professor Boggs’ Ph.D. advisor at UC Davis, and the talk ended with both professors making a pretty strong plug for why more students should consider majoring in Women’s and Gender Studies if their schools have the department. Grewal fondly remembered one of her advisees from Yale who is a policy analyst who has worked extensively on the Green New Deal.

“This was an immensely proud moment for me,” Grewal said. “She’s a WGSS AFAM major! That thinking came out of WGSS and AFAM, and that thinking said, ‘we gotta think big and we gotta change the world, but we have to create economies that care about all kinds of people but are also green!’ She brings a careful intersectional understanding to the issue.”

“When people ask, ‘What can you possibly do with a women’s studies major?’, this is it,” Kaplan finished.

Saadia Naeem can be reached at snaeem@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed