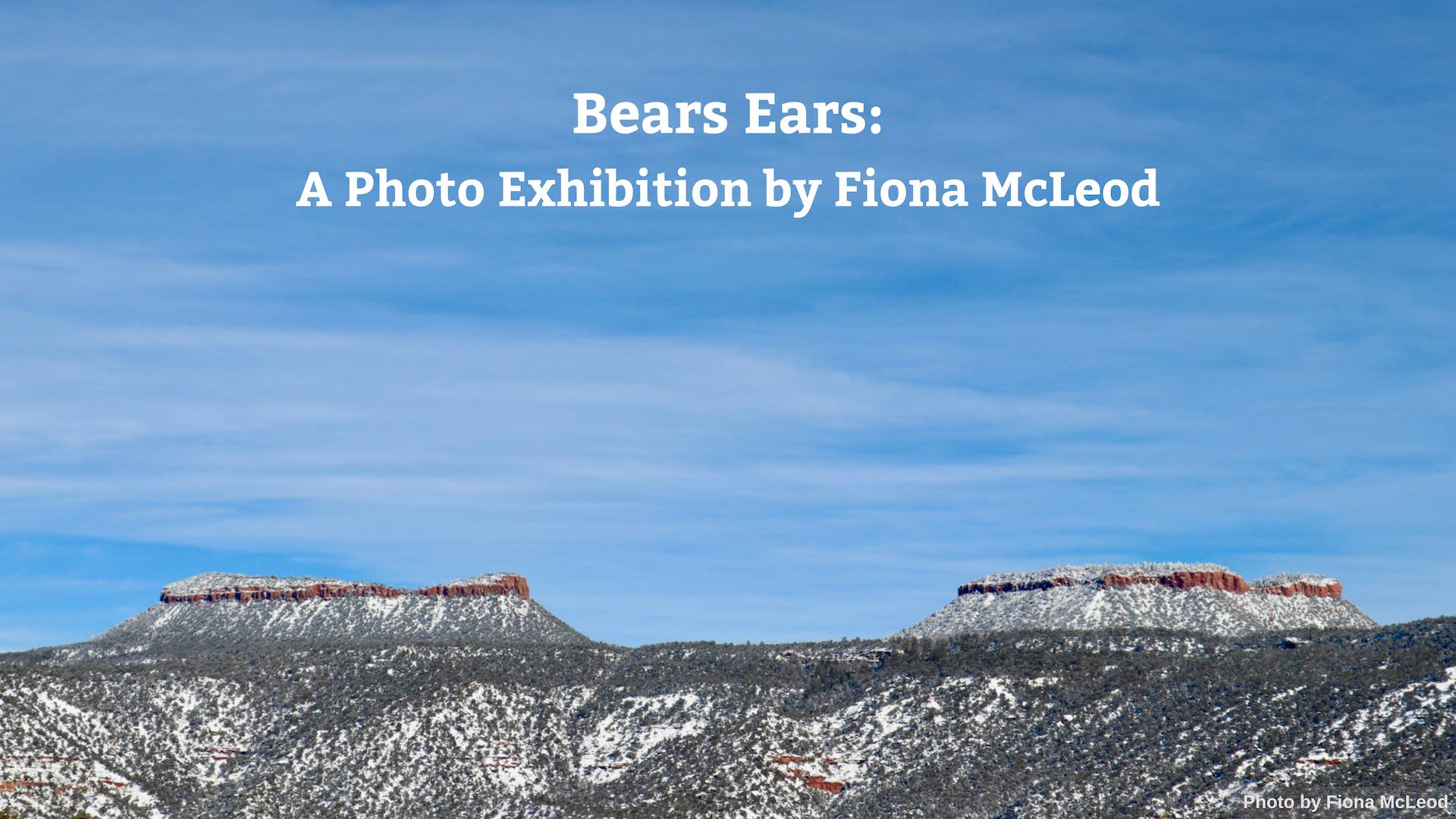

Combining deft landscape photography and a deceptively complex subject, a recent photo exhibit on the Bears Ears National Monument, which went up this Monday in the University’s Zilkha Gallery, is worth seeing before it comes down at the end of the week. The exhibit features photographs that Fiona McLeod ’19 took while conducting field research in the region for her Honors Thesis.

The Bears Ears region’s geographic beauty alone makes it a fitting subject for a photo series, but the land also has a long history of cultural significance to multiple Native American tribes in the area.

“[The] background of Bears Ears is that it is a profoundly sacred landscape in Southeastern Utah,” McLeod told The Argus, explaining this history. “So environmentally it’s a very complex place, but then also there’s hundreds of thousands of Native American burial sites, and village sites, and trails, and places of sacred and spiritual significance…. It figures into a lot of different tribal origin stories and migration histories, and to this day the indigenous people in the area continue to go there and practice their sacred ceremonies.”

Despite its importance to local indigenous peoples—and despite their attempts to gain legal protection for the land—preservation of Bears Ears has long been threatened by extractive industries such as mining and oil drilling, as well as by the region’s serious looting problem (thanks to an active black market for stolen Native American artifacts). After struggling to find support from the Utah state government, five local tribes formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition in 2015. The coalition submitted a proposal to President Obama seeking to make the area a national monument in order to better preserve it, and in the final weeks of his presidency, Obama finally created the Bears Ears National Monument.

“He designated 1.35 million acres when they had asked for 1.9, but it was still this huge historic win in which, for the first time in an American environmental conservation project, the voices of indigenous people were going to be honored and recognized and they were going to be an equal part in the actual implementation of the management plan, which has never happened before,” McLeod said. “So it was this huge moment of hope and forward progress, and then a year later, Trump reduced the size of [the monument] by 85 percent, which he did at the same time as reducing Grand Staircase-Escalante which is also in Utah, and it was the largest federal rollback of protected lands in US history. The people I talked to in the area are pretty steadfast that it was racially motivated and an effort to undermine tribal sovereignty…. [Now] that land that was protected and is now not protected is once again open to be leased out to these extractive industry corporations.”

McLeod’s photos of the Bears Ears region are visually stunning—showcasing the vast, sweeping geography that Utah is known for—but viewed in the context of this ongoing fight to protect the land, they take on even more poignancy. For McLeod, who is writing her thesis on the monument, this fight is what originally drew her to research Bears Ears.

“I’m majoring in American Studies with a concentration in Indigenous Studies, and around my sophomore year is when I got really interested in looking at the intersections between American environmentalism, indigenous rights and recognition, and sovereignty politics,” McLeod said. “That was kind of on my radar, that sort of environmental and indigenous history of the U.S., and then as I was picking my thesis topic I was aware that this indigenous-led movement to protect Bears Ears was going on, and right when thesis time hit was when it was designated and the size was reduced.”

The influences that drew McLeod to Bears Ears extend further back than her time at Wesleyan, however. As she explained to The Argus, her parents’ careers have also impacted her interest in both photography and indigenous issues.

“Landscape photography has been one of my artistic interests for my whole life,” McLeod said. “My parents are documentary filmmakers, and my dad is a professional photographer, so I grew up with that, and their films are about this intersection of environmentalism and indigenous politics. So I’m kind of just following in the footsteps of my parents who have done this work.”

While the risks that mining companies and lack of federal protection pose to the future of Bears Ears—and other environmentally fragile indigenous lands—are obvious, McLeod is quick to point out that these threats come from both sides of the political spectrum. Liberal environmentalist movements also have a long history of sidelining—or even directly oppressing—Native American tribes, an issue that she addresses in her thesis.

“I really got interested in how environmental conservation projects, in the U.S. specifically, developed as westward expansion was happening and the…notion of the American wilderness as a very distinctive and unique form of American identity was dependent on this figure of the noble savage. The kind of environmental conservation ethos in the U.S. is based upon this dual racialization of the landscape and then also taking those supposedly inherent characteristics of wilderness and imposing them upon the people who live there.”

One common example of this conflict of interests is conservation refugeeism, which happens when a (usually indigenous) population is displaced from their home to create a national park or some other form of protected land.

“In the U.S., Yellowstone was the first national park, and when they created it they drew a boundary, and because that was then public land for public use and enjoyment, it meant that all of the indigenous people who live there were moved to a reservation nearby,” McLeod pointed out. “And so it’s this really insidious idea of public land as being public and for the greater good, but directly contributing to indigenous expropriation…. There are so many easily identifiable ways that settler colonialism impacts indigenous people, and the kind of liberal projects of environmentalism are often not critiqued on that side of it, so it felt important to me to do that. But it also felt important to look at how tribes at Bears Ears are in some ways through this designation reversing that history and working within this confine of American environmental thought while also creating this completely unprecedented management plan in which indigenous voices are a core component.”

Now, just over a year after Trump’s reduction of the size of the national monument, the fate of Bears Ears still hangs in the balance. Three separate federal lawsuits have been filed challenging the rollbacks, but there are also a number of oil and gas companies with leases on the now unprotected land. In light of this uncertainty, McLeod’s photos feel particularly crucial, forcing viewers to directly confront what’s at stake in the fight for Bears Ears.

“There’s the artistic side of it, which is that I was in a beautiful place and I wanted, for my own memory, to have these pictures,” McLeod said of her motivations for taking the photos. “But then also I think visual media creates an impact that written media sometimes can’t convey. So it just felt important for me to have a way for people to be able to actually see themselves in the landscape while they’re learning about it.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply