“This Between Shadow” Showcases Winter Session Theater Students’ Work

An anxious writer attempts to compose a letter. A woman in black lies on a bathroom floor. A man discovers mysterious notes to himself.

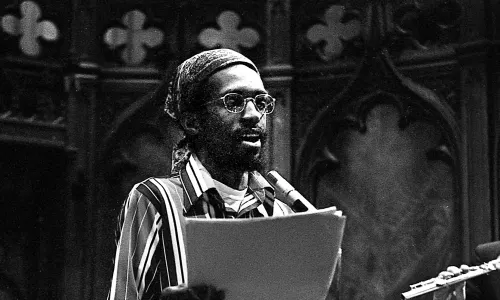

These seemingly disjointed vignettes make up “This Between Shadow,” a theater production that took place in the University’s Center for the Arts last week. “This Between Shadow” is the culminating performance of a class that took place during this year’s Winter Session—“Immersive Theater: Experiential Design, Material Culture, and Audience-Centered Performance.” The class was taught by Visiting Artist Tom Pearson, who spoke with The Argus last semester about his background and plans for the class. Pearson is one of the founders and artistic directors of Third Rail Projects, a theater company known for productions that directly involve audience members, and his course allowed students to combine their own interests and backgrounds with his unique artistic process.

“This Between Shadow” doesn’t follow the linear storyline of more traditional plays. Instead, the production consists of a series of independent scenes, each consisting of one or two performers and often requiring the direct participation of audience members. While these scenes don’t form an obviously connected narrative, and in fact were created separately by their performers, there are some common themes that emerge over the course of the show.

“We were all given basically two five minute [segments] for our scenes, and we developed them independently,” Nathan Pugh ’21, one of the students in Pearson’s class, said. “However, we were all working within the same themes of being lost, double-ness, shadows, and creating maps.”

Another unconventional aspect of the show, which begins in a darkened room in Zilkha Gallery but takes place across the CFA, is its setting. Rather than requiring the audience to remain seated in front of a stage, “This Between Shadow” guides them from room to room and building to building. In contrast with other plays which begin with a story and attempt to fit that story to the existing space, “This Between Shadow” was created after the students had already chosen and examined the CFA as a setting.

“Because we all were using the space to influence our scenes even before we had written them, we were really inspired by the CFA,” Pugh explained. “Since there were limitations to how much we could change the space, we really had to use what was there and try to bridge the physical journey the audience was taking with the emotional journey we wanted them to have. Those tunnels are honestly kind of creepy, so maintaining that sense of mystery while still propelling the audience forward through the space was a lot of fun. [Another] focus was to kind of subvert the way in which Crowell is usually used. So instead of having any kind of performance onstage with the audience in the seats, we used all the small spaces around the main theater and used the big open space sparingly. That’s a space people are pretty familiar with, so to be able to shift their perspective and make them see something they’ve seen so many times as new for the first time was my goal when creating my scene.”

Choosing a setting before writing a script, rather than vice versa, leads to a uniquely close relationship between space and performance. In one scene, which takes place in the Zilkha elevator, an increasingly nervous man tries repeatedly to write a letter to an estranged friend, failing to get more than a few sentences into each new attempt before rejecting it and starting over. The small size of the space (which is strewn with the writer’s discarded earlier drafts) and the fact that the room is literally moving (the elevator travels downwards, eventually depositing audience members at the location of the next scene) adds a sense of claustrophobia and disorientation that emphasizes the writer’s frantic demeanor. This careful consideration of space is evident throughout the show.

“A lot of our creative inspiration came from the CFA space,” Dylan Shumway ’20, another student in the class, said. “We spent the first few days of the class finding a campus space that had potential to be turned into an immersive space. Once we agreed on the CFA, each person gravitated towards some aspect of the gallery, tunnels, or concert hall that caught their interest and built that aspect out into a larger experience. The performers in the tunnels were drawn by the many marks and labels along the tunnel walls, a facet that carried into their scene that had audience members adding new lines to the walls. The performer by the restrooms in Crowell was taken by the many entrances to the small lobby space, having people pass through the space multiple times to see the scene change. I was drawn to the atypical, birds-eye view of Crowell from the choir loft, turning it into a scene about mapping the world from above. By focusing on the space and exploring all the possibilities it holds for conveying experience, we were able to craft scenes that simultaneously felt of the space and built a new world upon it.”

As suggested by the title of Pearson’s immersive theater course, the audience plays a vital role in the final production. While the performers guide audience members from scene to scene, each individual viewer will have a completely unique experience, as they may not see every single scene, and will see them in a different order.

“Tom talked a lot about the audience being the protagonist of the show, and we kind of extended that into the audience being their own narrator, piecing together all of the fragments and images we presented them into their own personal story,” Pugh said.

Audience members also interact directly with performers, who often directly ask them questions or wordlessly guide them to perform certain actions. The fact that the show relies on audience participation poses both challenges and benefits for the production, Pugh and Shumway explained.

“Audiences are never going to behave 100 percent how you expect them to; they will not follow instructions, or [will] be nervous to participate in events if they’re not properly invited to, and even sometimes they’ll try to rebel against the scene that you’re trying to make,” Pugh said. “But as an immersive theater performer, it’s your job to guide them and make them feel comfortable engaging in the work. We talked a lot about consent and slowly building trust with your audience member over the course of the show. We also talked about how body language, gesture, and tone of voice all can contribute to making sure that everyone feels comfortable in the space. The advantages of audience participation [are] that you get to really connect with your audience members, and be continually surprised by them. For example, I was able to have one-on-one scenes within the show, which allows for this very personal and sometimes intimate connection with the person you’re performing for. It has a cinematic quality that I don’t usually find in theater, that I really enjoy.”

Shumway expressed similar sentiments, explaining the effort required to plan for audience members who may behave in unexpected ways.

“The high level of audience engagement encourages a different creative process than traditional theater,” he said. “Giving the audience agency opens a lot of possibilities that traditional theater lacks, placing greater emphasis on interaction than observation. However, the audience’s ability to participate in scenes has the potential to go in unexpected directions. When we were creating our scenes, we often brainstormed ways that people may interact with the environment that was outside of our intended experience and then created ways to loop the audience back into the main focus. It’s a constant balance between making the audience feel empowered to engage with the world and keeping them within the experience to avoid breaking the experience.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply