Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard,” which played last Saturday at the film series, still resonates today as a brilliant experiment in Hollywood self-parodying that, for its time, radically blurred the lines between art and life. By casting actors to play rough imitations of their real selves, Wilder evokes powerfully authentic performances that draw out the psychological potency between a trio of characters who cruelly manipulate one another for their own ends and yet at the same time desperately need each other.

The film uses a non-chronological narrative device by beginning at the end of the story with the main character and voice-over narrator, Joe Gillis, being pulled out of the swimming pool of a famous movie star by police like a “beached whale.” By beginning with the death of our not-so-heroic main character, the film immediately instills the sense of fatalism typical of noir films and eerily allows our narrator, floating somewhere between our world and the next, to guide us through his internal and external conscious experiences as he remembers them. After the narrator enigmatically describes that the “poor dope always wanted a pool…. When in the end he got himself a pool, only the price turned out to be a little high.” The film then flashes back to the beginning of the story to describe the character’s materialistic conquests that would ultimately lead to his demise. The film’s opening sets up the narrator’s morose, sardonic tone, emblematic of the noir genre, and also exhibits the snappy but poetic one liners that define the film’s incredible screenplay.

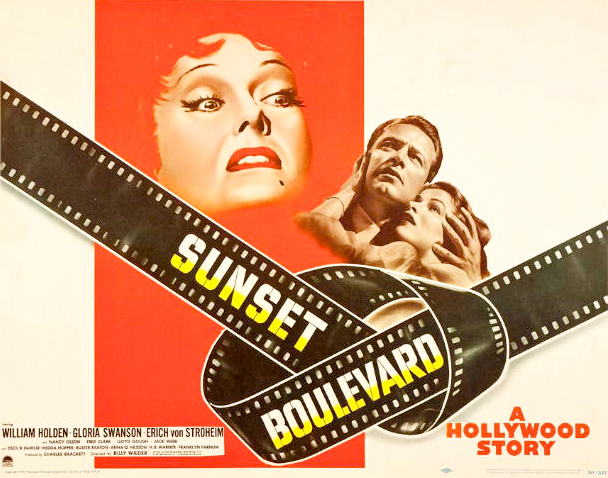

Gillis, a struggling young screenwriter on the brink of eviction, is being chased by two debt collectors when he conveniently pulls down a side street leading to a decrepit old mansion with an empty garage where he can stash his car. Gillis explores the mansion, where he is mistaken by the butler and the homeowner, Norma Desmond, as the coffin collector for her deceased pet monkey, a plot device that foreshadows the mystique of her character and the way she will make Gillis her new pet. Desmond turns out to be a middle-aged silent film actress who hasn’t been employed in years after falling out of graces with Hollywood, not unlike Gloria Swanson who plays Desmond and at the time of the film’s production had been at a similar place in her career. Desmond, lonely and narcissistically deluded about her stardom and fanship, stuck in a past era where she was a silent film star, employs Gillis to edit the script she’s written for her comeback film and convinces him to sleep in the guest room where she can keep close surveillance on him. Her butler, Max Von Mayerling, mostly serves to feed Desmond’s narcissism by writing her fake fan letters that she willfully believes and by making sure she doesn’t kill herself during fits of melancholy, which is why all the doors in the house creepily have no locks. It is eventually revealed that the butler turns out to be a former great film director who discovered Desmond and has now become a slave to his artistic creation, adding another psychological twist to the dynamic between the three characters. Furthering the double meanings that Wilder instills in the film, the butler is played by Erich Von Stroheim, who was a once great silent film director that directed Swanson in several films but didn’t adapt well to sound films.

As Gillis works on the script, Desmond grows ever more controlling of his life by getting rid of his car, buying him all new clothing, and monitoring any attempts to escape the house. Desmond becomes convinced that a former film director is interested in her script despite Gillis’ discovery that the studio only wants her old-fashioned car for a scene in a new film.

While Desmond’s desperation and narcissistic manipulation of Gillis contrasts with his seemingly detached indifference to the whole matter, Wilder shows that he manipulates her just as much out of his his own financial desperation and subsistence. For this very reason, what makes this unstable psychological balance between the characters so dynamic is the sense that both characters hardly care at all for one another and yet emotionally or monetarily deeply rely on one another. The egoism, desperation, and loneliness behind these characters, for Wilder, clearly operate as windows into the psyche of Hollywood. Naturally though, the tenuous balance of coexisting personas and egos falls apart once Gillis starts working on a different script with a young female script reader at Paramount, who falls in love with him. Once Desmond finds out and tries to interfere in their relationship, Gillis threatens to leave leading Desmond to shoot him. He falls into the pool, bringing the narrative full circle, and Desmond, in a delusional state, revels in the attention she’s given by the police officers and news cameras.

The aimless and sardonic main character, femme fatale, and gothic themes clearly evince the noir qualities that run deep in “Sunset Boulevard.” And yet by making a parodic movie about the underpinnings of 1950s Hollywood in the heyday of noir, Wilder pulls back the curtains of the artifice of the industry to reveal another noir.

Through the relationship between a forgotten silent film actress and a young screenwriter who embodies the detached male noir character, “Sunset Boulevard” captures the 50s generational conflict of an old world, still traumatized by the atrocities of World War II, being left behind by the new world of consumerism and optimism. The dark pessimism of the film lies in the tension between the two main characters who embody these two worlds, seemingly at odds and yet uncannily similar in their mutual neediness and self-obsession.

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply