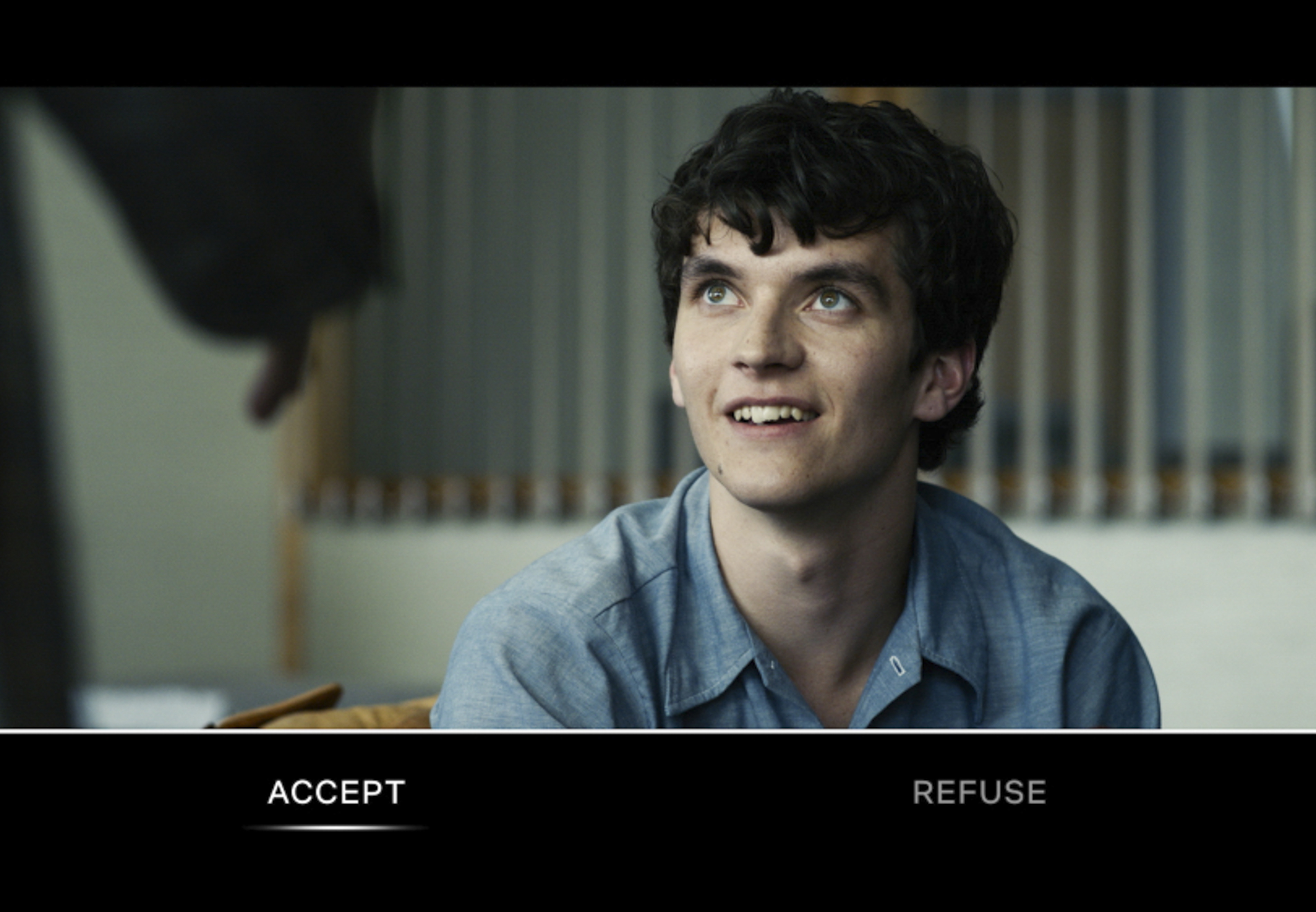

c/o variety.com

For the entertainment company Netflix, which, much like other contemporary online corporations, has built a media empire on the enticing appeal of consumer choice, it would only make sense that they would be at the forefront of the development of interactive films that allow viewers to “choose your own adventure.” However, released on Dec. 28 to uproarious anticipation, Black Mirror’s “Bandersnatch” falls short in almost every category for what makes a good film in its attempt to conceptually incorporate the interactive components.

Somehow, “Bandersnatch” manages to make arguably the most exciting technological invention in film since the advent of sound films feel like an already exhausted gimmick, and thus the experience of reviewing it more like describing the user experience of an Amazon product or the newest Apple gadget. At its best, the psychological thriller is able to reflect unoriginal but thought-provoking plot themes of the nature of reality, multiverse, simulation, and our experience of time within the viewer experience of the film. At its worst, “Bandersnatch” reduces the incredible and infinite narrative capabilities of interactive film viewing into a frivolous joy ride of mere consumer choice.

Given the multiple endings that the interactive components can lead to, it could pose somewhat of a challenge to review for an audience that literally might not have seen the same movie. However, after extensive Reddit research and close examination of the “Bandersnatch” flow chart, miraculously posted four hours after the film’s release presumably by the Reddit gym rats, I can attest that the interactive elements more or less offer multiple paths to the same kind of ending.

Set in 1984, the movie capitalizes on the increasingly popular ’80s aesthetic as well as capturing the anxious anticipation and excitement of the emerging internet, tech age. The story, as well as our role as interactive viewers, centers around Stefan, a troubled young game developer, trying to adapt a science fiction interactive novel called “Bandersnatch” into a video game. After signing a deal with a major video game company, Stefan meets Colin, a renowned video game developer who offers Stefan guidance as he works on the project. Stefan starts to become obsessed with the author of “Bandersnatch,” Jerome F. Davies, who had had drug-induced hallucinations that he was being controlled by spirits and eventually kills his wife in madness. For Stefan, who has his own psychological struggles, Davies’ story begins to deeply unsettle and eventually uncontrollably torment him. The first major narrative split happens when the option is given to the viewer to decide for Stefan to work on the video game at the company’s office, which is a dead end option where the video game fails after its release and starts the story over again. Eventually, the viewer must choose for Stefan to work on the video game alone on Colin’s suggestion that “a bit of madness is what you need.”

At home with his concerned father, Stefan works feverishly on the video game and revisits dark memories of his mother’s death in a train accident, for which he partially blames himself, but mostly his father. After weeks of isolation and unsuccessful work on the video game, Stefan’s father forces him to go see his therapist, Dr. Haynes, where he has a haunting daydream, the reality of which is left uncertain, in which Colin and Stefan take acid together. During the trip, Colin rambles to Stefan about the existence of parallel realities, the construction of time, government surveillance, and the great spirit that controls all our actions before jumping off of a building. The topics of this conversation creep into Stefan’s already fragile psychological state, and he starts to think that he is being controlled by an unknown force. Ultimately, he discovers that we, the audience, are making decisions for him, and he kills his dad and, in many versions, unsuccessfully finishes his video game.

Conceptually, the film touches on many potent metaphysical and ontological questions about reality, free will, and time that in many ways capture the contemporary dialogues among public figures in politics and science on the nature of truth and simulation theory. Despite the film’s conceptual strengths, it doesn’t really add anything intellectually to these discussions that hasn’t been said. Especially when compared to the reality bending “trippy” canon of “The Truman Show,” “The Matrix,” “Mr. Nobody,” and even last year’s Errol Morris docuseries “Wormwood,” “Bandersnatch” really just seems to rehash old ideas.

Of course, the novel element of “Bandersnatch” lies in its incorporation of the interactive elements that thematically intersect with the plot and change our relationship with the characters and their development. However, for almost every interactive component that actually affects the narrative or amounts to some alternative ending, there also are meaningless choices that don’t influence the plot except for what ’80s hit song Stefan will be listening to (Thompson twins or Now 2?), in such a fashion that it might as well just say sponsored by Spotify in the right-hand corner.

Unfortunately, even the interactive pieces that actually influence the narrative also end up being the film’s weaknesses. Non-linear plots can be successful and offer interesting perspectives on our experience of time and narrative, but given the complexity of the ideas that “Bandersnatch” tries to grapple with, along with the interactive elements that already destabilize a clear storyline, the plot ends up being convoluted enough to detract from the viewing experience. In many ways, the film seems to add interactive plot choices at the cost of actually developing a succinct storyline, which is only exacerbated by the unoriginality of the concepts that it uses the interactive elements to reflect. In addition, the film doesn’t give the audience enough time to actually relate to the main character and understand his backstory before we’re put in the position to make choices for him, which makes the early choices given to us in the movie feel pointless. The lack of character development could be “Bandersnatch’s” biggest failing by missing the area with the most potential for interactive films, to even more drastically engage audiences in characters by giving them choices in what they do. Instead, “Bandersnatch” actually makes Stefan aware that he is being controlled by a future media company by the end of the film and thus actively separates the character from the audience making decisions for him.

This failing of character development is the most disappointing aspect of Black Mirror’s newest experiment, a TV series that has been so successful at evoking potent social commentary largely through the feelings of terror and entrapment by its characters that we can identify in our own modern lives. While “Bandersnatch” shows glimpses of the potential for interactive films, it comes up short and will most likely be remembered as an innovative but hollow psychological thriller.

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.