Investigating Cause of Death: Serial Killer True Crime Reflects an Author’s Deadly Obsession

Content warning: This article includes themes of sexual abuse and gender-based violence.

On April 21, 2016, true crime writer Michelle McNamara, age 46, was found dead by husband of 11 years Patton Oswalt. Although it would take another year for a coroner to reveal her killer to be an undiagnosed heart condition combined with the effects of several drugs, Oswalt, a famous comedian, immediately suspected that it was an accidental drug overdose: she had taken a Xanax the night before to try and get some rest, as her obsessive investigation into a nightmarish cold case often kept her up at night.

Reading the posthumously published “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark” now, it is impossible to forget two pieces of context that author McNamara could not have known about her own work: first, that her investigation, which serves as the foundation of the book, had indirectly killed her; second, that its subject, a sadistic rapist and killer, would be caught mere months after its publication. Reading “Dark” has then become an all-the-more fascinating and heartache-inducing endeavor: you are devouring a work that is simultaneously an outdated artifact and a cause of death.

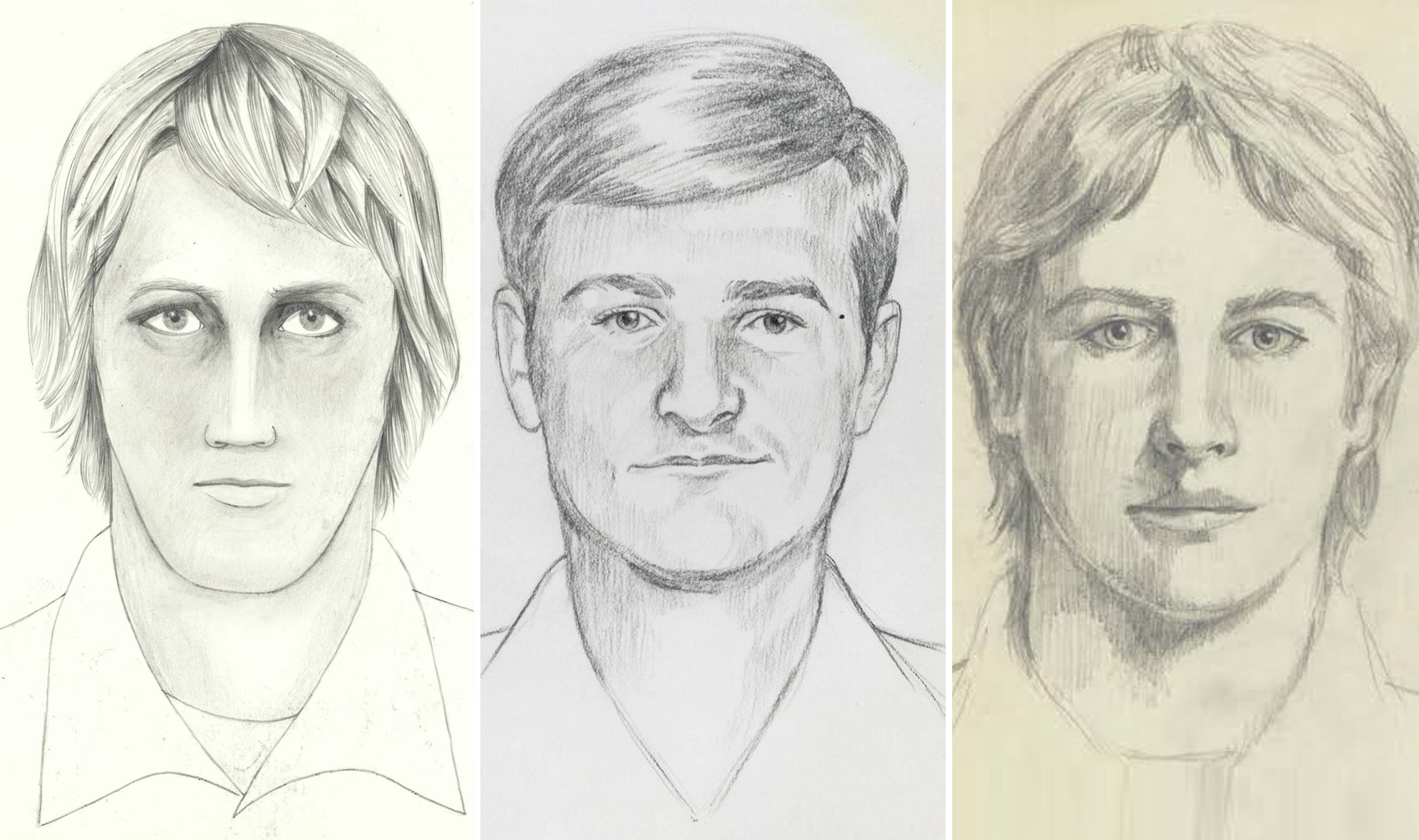

“Dark” is a nonfiction narrative that combines interviews, crime scene evidence, contradicting theories, and so much more that all center on one man who terrorized California in the 1970s and ’80s. The book’s subject is known by many names: the East Area Rapist. The Original Night Stalker. It’s a sad irony that, though McNamara would never know that the man she was tracking was named Joseph James DeAngelo, she was the one who christened him with the moniker that holds most popular today. The Golden State Killer.

The case ensnared her for several years for immediately apparent reasons: even without these added layers of intrigue, the Golden State Killer is an irresistibly disturbing mystery. He is now suspected of 50 rapes and 13 murders. He is known for staking out his victims’ houses beforehand, binding the hands of his targets, and speaking through clenched teeth. And those are among his less disturbing behaviors: he also entered and left the house naked from the waist down, forced women to masturbate him with their tied hands, and killed with weapons that he found inside the house. And then there were the cruel mind games that he played.

“The blindfolded victim tied up in the dark develops the feral senses of a savannah animal,” McNamara writes, describing a typical account compiled from several victims. “The sliding glass door quietly shutting registers as a loud, mechanical click…. The dread sense of being watched, of being pinned down by a possessing gaze she can’t see, is gone. Thirty minutes. Forty-five. She allows her body to slacken almost imperceptibly. Her shoulders fall. It’s then, at the precipice of an exhale, that the nightmare snaps into action again—the knife grazes the skin, and the labored breathing resumes, grows closer, until she feels him settling in next to her, an animal waiting patiently for its half-dying quarry to still.”

“Dark” itself is astounding, at first. McNamara’s meticulous writing talent is lauded in the fawning introduction by “Gone Girl” writer Gillian Flynn and is demonstrated throughout Part One (of Three), which was mostly completed by the time of her death. The first chapter alone slowly and carefully untangles a single crime scene: the murders of David and Manuela Witthuhn and the latter’s rape, as told in the free indirect style from brother-in-law Drew Witthuhn’s perspective.

McNamara paints a devastatingly clear picture of not only the crime scene but also the complex relationships among the Witthuhns. With her evident compassion, candor, and levelheadedness, McNamara gains the reader’s trust effortlessly by depicting them in a sympathetic but exposing light, describing their personal flaws without judgment and introducing soft compliments when appropriate. One of her many talents as a writer is, as Flynn describes in her introduction, her humanity.

She also offers help to the reader in the ebbs and flows of her prose: McNamara can introduce information in a burst, like ripping off the proverbial Band-Aid, or over the course of paragraphs, allowing for a slow digestion of particularly intense details. All of this is to say that she is an undeniably masterful writer, with a clear and careful vision for the book.

It is because of her talents, however, that the reader is set up to be let down. The chapter “Ventura, 1980” ends jaggedly with a note from editors Billy Jensen and Paul Haynes, who put together and published the book after McNamara’s death. They explain that she had planned to explore that particular case in much more detail but had yet to draft exactly what she wanted to say.

It is at this moment that the reader’s focus begins to shift from the identity of the Golden State Killer to the aching distortion of what would have been an undoubtedly meticulous and compelling work. The following chapters are reconstructed from various drafts of McNamara’s works. Where readers felt as though they were narrowing in on him, they now feel pulled in a million partially-explored-and-then-abandoned directions. The shift could be seen as an induced experience that helps readers empathize with the many fraught and frustrated investigators and detectives, but that would be reading too much into a book that was left tragically and tangibly unfinished.

The rest of the book becomes both overly technical and too human: Jensen and Haynes struggle to integrate the former detectives’ raw personal struggles with the various conflicting theories about the Golden State Killer’s profession, motives, and altering physical description. Much of the prose mirrors that of McNamara’s pieces in the Los Angeles Magazine, as the chapters are based on drafts of such articles in which she offered brief updates on the Golden State Killer’s case in “The Five Most Popular Myths About the Golden State Killer Case” and “UPDATE: Investigators Have a New Lead on the Golden State Killer.” “Dark’s” methodical, ever-deepening exploration of the Golden State Killer is gone, replaced with scattered snapshots that resemble hundreds of pieces of evidence hung on a maddened detective’s cork board, yet to be connected by any telltale red string.

A moment of haunting redemption comes in McNamara’s epilogue, which she fortunately finished before her death. Despite the faults of the middling sections, and despite the reader’s knowledge that the killer has been captured, it cannot lose its tantalizing and bone-chilling effect. McNamara speaks directly to the killer, taunting him, precisely cutting him down to the pathetic man that he is. Her hunger to see him unmasked is at its most naked at the final hypothetical scenario that she plays out: his capture.

“One day soon, you’ll hear a car pull up to your curb, an engine cut out,” McNamara writes. “You’ll hear footsteps coming up your front walk…. The doorbell rings. No side gates are left open. You’re long past leaping over a fence. Take one of your hyper, gulping breaths. Clench your teeth. Inch timidly toward the insistent bell. This is how it ends for you. ‘You’ll be silent forever, and I’ll be gone in the dark,’ you threatened a victim once. Open the door. Show us your face. Walk into the light.”

On April 24, 2018, two years and three days after McNamara’s death, DeAngelo was charged with the Golden State Killer’s crimes. He will be tried for all of the murders—the statutes of limitation on all of the rapes have been exceeded—though the trial is not expected to take place for a few years. “Dark,” which had been released two months earlier, was not directly related to his capture: a DNA hit off of a relative eventually led detectives to the killer’s door, though investigators recognized the #1 New York Times Bestseller for keeping public interest unusually high in the case’s outcome.

After DeAngelo’s capture, Jensen told The New York Times that he and Haynes plan to add a chapter to “Dark” that delves into the former police officer’s past. So the book itself lives on, growing and stretching as details are uncovered one by one.

McNamara herself lives on in another way, primarily through her widower. Oswalt has continued to perform stand-up comedy since McNamara’s death, often directly discussing themes of grief, recovery, and his changing relationship with their young daughter. He pens an afterword in “Dark” that reads as a love letter in the style of his stand-up, complete with funny anecdotes about her brilliance and simple, kind descriptions of his late wife as the crime fighter that he clearly saw—and sees—her as. His words, alongside hers, only extend readers’ yearning to understand McNamara and her obsessions.

She is undeniably a subject in her own piece. “Dark” transcends its true crime genre to become something even more fascinating with its smattering of autobiographical anecdotes that its author had chosen before her death. An early chapter is entirely devoted to a cold case from McNamara’s childhood that sparked her true crime fascination, and other details about how consuming and personally devastating her obsessive investigation had been emerge over the narrative. Flynn expresses uninhibited admiration for McNamara and laments not becoming closer with her; she recalls taking a drive through McNamara’s childhood neighborhood, confused as to why she was there, and reflects, “I was in my own search, hunting this remarkable hunter of darkness.”

As readers, we are much like Flynn, seeking to understand a person who is already gone, but who ensnares us much like the Golden State Killer ensnared McNamara. “Dark” is fundamentally imbued with the grief of the loss of its author, and we are fascinated, and we are left to glean as much as we can about her from the clues she’s left behind.

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu.

Michelle’s actual cause of death was due to fentanyl. A drug now mixed in other drugs by people who have now killed 10’s of thousands. Serial killers in lab coats are responsible.