Confession. The ten-minute meeting you have with a priest to rid of that nagging, guilty feeling after a wild night out on Fountain. The decision you make when debating whether or not to tell your mom what you dressed up as for Halloweekend. The act of confessing our personal matters is deeply integrated into modern society. We feel the urgent need to release any feeling of guilt or remorse, hoping that simply admitting our mistakes will set us free. But what does the act of confession really mean? What effect does this practice have on our personal lives?

Professor of Religion at Barnard College Elizabeth Castelli shed light on the subject of confessions in her talk, “True Confessions! The Art and Politics of Truth Telling.” On Thursday, Oct. 25, students and professors arrived early to find a seat in PAC101, excited to hear Professor Castelli’s intricate research and experiences in the artistic culture of truth telling, and how modern day truth telling connects deeply to the Catholic tradition of confession.

Professor Castelli began her talk by introducing an array of artists currently interested in the art of truth telling and its impact on society today.

Sophie Calle, the first of Professor Castelli’s spotlight artists, used her experience in installation art to create an interactive confessional at Green Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. The installation allows visitors of the cemetery to reveal their deepest secrets to Calle’s art piece either through written, anonymous confessions or, if lucky, personal meetings with Calle herself, that mimic the traditional catholic priest confessional experience.

“At a distance Sophie Calle herself was seated under a leafy tree on a wooden chair across from another women who was confiding her secrets face to face,” Castelli said. “The scene approximated one part psychotherapy and one part sacrament of reconciliation. Calle’s presence and availability for one on one confession had been widely advertised beforehand and the time slots for this personal intimate exchange and the opportunity thereby to participate more personally and fully in the artist’s project had long since filled up. Sophie could hear only so many confessions.”

Sophie Calle’s installation is entitled, “Here Lie the Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetery” and will continue to interact with its visitors for the next 25 years. This installation has inspired profound conversation on the topic of biblical confession and its role in modern day secrecy, unburdening of guilt, and cheap grace.

When discussing the reason Calle chose to create her art in a cemetery, Professor Castelli explained that the image of gravestones and death evoke an understanding of eternal secrecy. The secrets confessed in the cemetery are literally “taken to the grave.”

“We are asked to forget that there is no actual grave, no gruesome disinterment required, just a small hatch at the base of the oblis… and yet the effect is the creation of the artifice of secrets taken to the grave, that and the purifying promise of fire,” Castelli said.

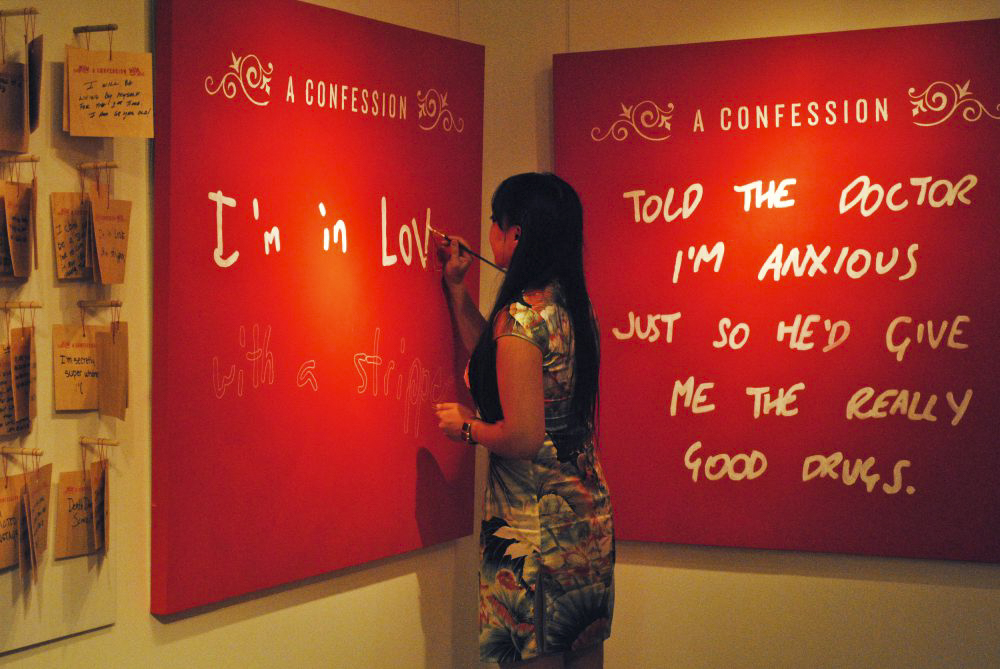

Castelli then introduced Candy Chang, an artist who created an installation entitled, “Confessions” in the hopes of understanding human forms of emotion and life experiences. The installation included a confession booth where, like in Calle’s piece, viewers can write their deepest confessions. Candy Chang’s website explains that the installation was created with the desire to foster kinship within community. People write their confessions knowing that strangers will see them, allowing for a sense of communal understanding and solidarity.

Professor Castelli went onto detail the interaction between the public and Chang’s installation.

“Chang invited people to inscribe their confessions and display them in galleries in Las Vegas, in Athens, in Minsk, and in London over the course of several years, beginning in 2012.”

Professor Castelli’s third example of confession through art was an instillation by Urban Matter Ink and Third Pattern Films. Their installation is an interactive public confessional called “Pop Up Confessional” and allows its visitors to take refuge inside of a makeshift confessional and speak with a AI priest.

“The confessional encourages people to talk about the hidden and unseen aspects of their lives,” she said. “The priest in this case is an emotionally intelligent entity called the conversational companion, or coco for short. The confessional allows the AI program to build upon conversational capabilities, thereby becoming a better conversationalist.”

As Castelli began to connect more intimately with her audience, she introduced questions and concepts that differed slightly from her earlier analysis of confessional artistic expression, with the hope that they might resonate with us as a community.

She introduced the world of reality television and its unique acceptance of transparency and self-disclosure. Though some may claim that reality TV is filled with families that give up their privacy in exchange for cheap fame, others, like Castelli, further analyze this transparency and see the confession and truth telling that underlies their public intimacy. Reality TV, she explained, is a confessional outlet for its subjects to express themselves unabashedly, with the hope that their viewers relate to their confession rather than detest them for it.

To close, Castelli made obvious the connection between the act of confession and the Kavanaugh trial. Castelli’s words had resonated with her Wesleyan audience, and the idea of applying the idea of confession to such a contentious political debate suddenly made complete sense. Castelli explained that if Kavanaugh had confessed to sexual assault, he would potentially have had the opportunity to move forward. Instead, he failed to acknowledge any wrongdoing and professed a counter confession in his defense.

Through presenting an array of captivating art expressions, popculture analysis, and current political understanding, Castelli brought the idea of traditional Catholic confession to the hearts and minds of the Wesleyan community. Her words inspire a need to see secrecy, truth telling, and confession in all aspects of society.

Calia Christie can be reached at cchristie@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply