c/o dhadesigns.com

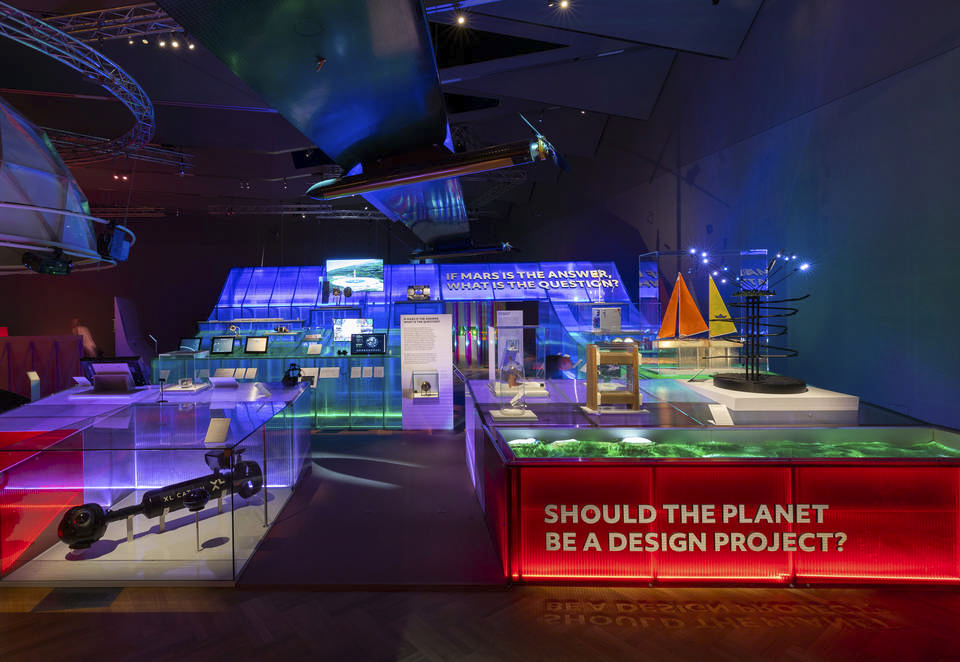

Descend an escalator in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum of Art into an exhibition called “The Future Starts Here,” and you will enter into a peculiar room of provocative questions and provocative objects. Strange, warped music plays in the background. Objects are displayed on glowing pink, blue and green plastic-y surfaces, flooding the room with varying effusive lights.

In effect, the room is glowing. For the most part, it is also devoid of art, or at least art in the traditional sense. Instead it houses modern gadgets and ideas that feel like the threshold to something greater, something newer: small catalysts for a future world unlike our own.

“The Future Starts Here” is on display in the V&A from Oct. 6 to Nov. 4. It is organized into four distinct sections: self, public, planet and afterlife. Each exhibition explores the ways in which technology influences, and may continue to influence, our perceptions and lives. All of the objects on display are real, working objects, though many are models and prototypes. “The Future Starts Here” is, in a way, a cabinet of curiosities. It is a display of strange, fascinating things, which, once given a closer look, appear to draw out humanity as well as quell it.

The exhibit simultaneously embraces and rejects the objects and the futures they embody. Many of the objects are displayed alongside questions probing at their use and invention, like “Who should own, police and regulate the internet?” and “If Mars is the answer, what is the question?” While many objects are exhibited without obvious connotation, overall, an agenda is clear: We must remain aware of the ethical implications of innovation. Some objects are clearly displayed in a positive light; an underwater probe that maps the ocean floor, a model of a city that includes green spaces and solar-paneled roofs. Others, not so much; an UberEats bike emblematic of algorithms taking the place of human bosses, a running video of a family connected to Amazon Alexa but disconnected from each other.

Museum-goers first enter into the self section, which displays objects aimed at perfecting or cataloging individuality. Displayed alongside objects that are strange and uncomfortable are ones that we know quite well: A Fitbit bracelet, an iPhone, virtual reality goggles. Are we already cyborgs? These objects are wearable technology that enhance our experience of reality, that we have imbued with our data, our memories, our perceptions. Here, displayed in an exhibition, they are rendered useless as tools. Suddenly, even as they are on our bodies, they are foreign. The self section also displays stranger objects, such as a portable DNA testing kit, forcing one to imagine a future in which DNA compatibility tests are administered, for example, before first dates. Two swimsuits that compress and massage muscles, designed for Olympians, float above the other objects. How can technology enhance our speed and endurance? Should it?

Exit Self, and visitors enter into a mock restaurant, which advertises itself as a restaurant for one, in this age of living alone. Visitors can sit at one of the small tables designed for a single occupant. The restaurant feels cold, and lonely, despite an assurance that the set-up enhances the feeling of community. Yet there’s something appealing about catering for, even celebrating, loneliness.

Moving forward is Public, which asks questions about technology and democracy: In what ways does technology improve or limit access to representation, to government? This section feels the weakest of the total exhibition. A pink “pussy hat,” for example, is on display as emblematic of organizing power post-Trump; the hat feels out of place in this cultivated cybertech world. Further along, models of cities and communal living arrangements are presented. Models include utopian visions of anarchist communities on floating islands, massive buildings dedicated to enhancing social bonds. These are fascinating. One must imagine the ways in which they enhance or diminish connection. Are we too reliant, now, on technology for human connection? How can innovative architecture change the ways in which we interact?

c/o dhadesigns.com

Further along, a chrome white dome suspended from the ceiling evokes future settlements on alien worlds, as well as the 1956 futurist art exhibition “This is Tomorrow!” which played at similar themes of science fiction, art and reality. Within the dome, a concave video about climate change plays on repeat. Participants can put on headphones and lie on their backs on soft padding, looking up at it, and feel enveloped by the film. The message of the video—that we must be aware of how our climate functions, and how it is changing—is more overt than other elements of the show.

The next portion of the exhibition is Planet, displaying objects that enhance our knowledge of space and natural planetary systems, as well as ways to enhance or surpass these systems. Planet explores habitability, terraforming, and the current space race to Mars. A small model of a Martian home is on display: it is semi-underground and dirt-covered, taking advantage of natural Martian material. The most interesting object in this section is also the most inconspicuous: a few leaves of paper with dense text. This is a copy of a bill, signed by President Obama in 2015, that allows US citizens and private companies to claim and own objects found in space. According to the didactic panel, President Obama signed this bill following a flyby of an asteroid near earth, estimated to contain 4.5 trillion dollars’ worth of platinum. This bill largely escaped scrutiny by the public eye, but it points to a precedent of allowing space to be claimed, rather than free use. Will a day arrive when Walmart owns Pluto?

The final section is Afterlife, and it is perhaps the most interesting. One of the more provocative objects in the section is a body-sized compartment, made by the company Cryogenics, that is designed to preserve bodies after they die to later be reanimated. This is predicated, of course, on one day inventing the technology to do so, but there are those who believe we will, and wish to have their bodies prepared for it. Currently, 2,000 people have signed up for this service. They wear alert bracelets which indicate that their body ought to be preserved on ice as quickly as possible after death. The effect of this display is a strange horror and fascination, and a wonder if perhaps one’s own post-death plans are lacking.

Another display focuses on an app, called Eterni.Me, which allows users to create an interactive digital avatar based on themselves. The app was inspired, partly, by an episode of the dystopian TV show Black Mirror, called “Be Right Back,” which warns against this very idea. The implications of the app are profound. Will there come a point when consciousness is code? It may seem like a far-fetched idea, yet advances in artificial intelligence point to a future in which this may be possible.

In the end, that’s the theme of this entire exhibition. Each of these objects has the capacity to, in some way or another, profoundly change the future. Yet the exhibition asks visitors to remember that they have the power to activate, or not activate, these objects, as well as the responsibility to decide. The exhibition is an imagining of the future, a display of objects that have one foot in today, and one foot in tomorrow. Yet the show is, in many ways, not about the future. Instead, at its core, “The Future is Here” embraces the now.

Emmy Hughes can be reached at ebhughes@wesleyan.edu.