Spencer Dean, Staff Writer

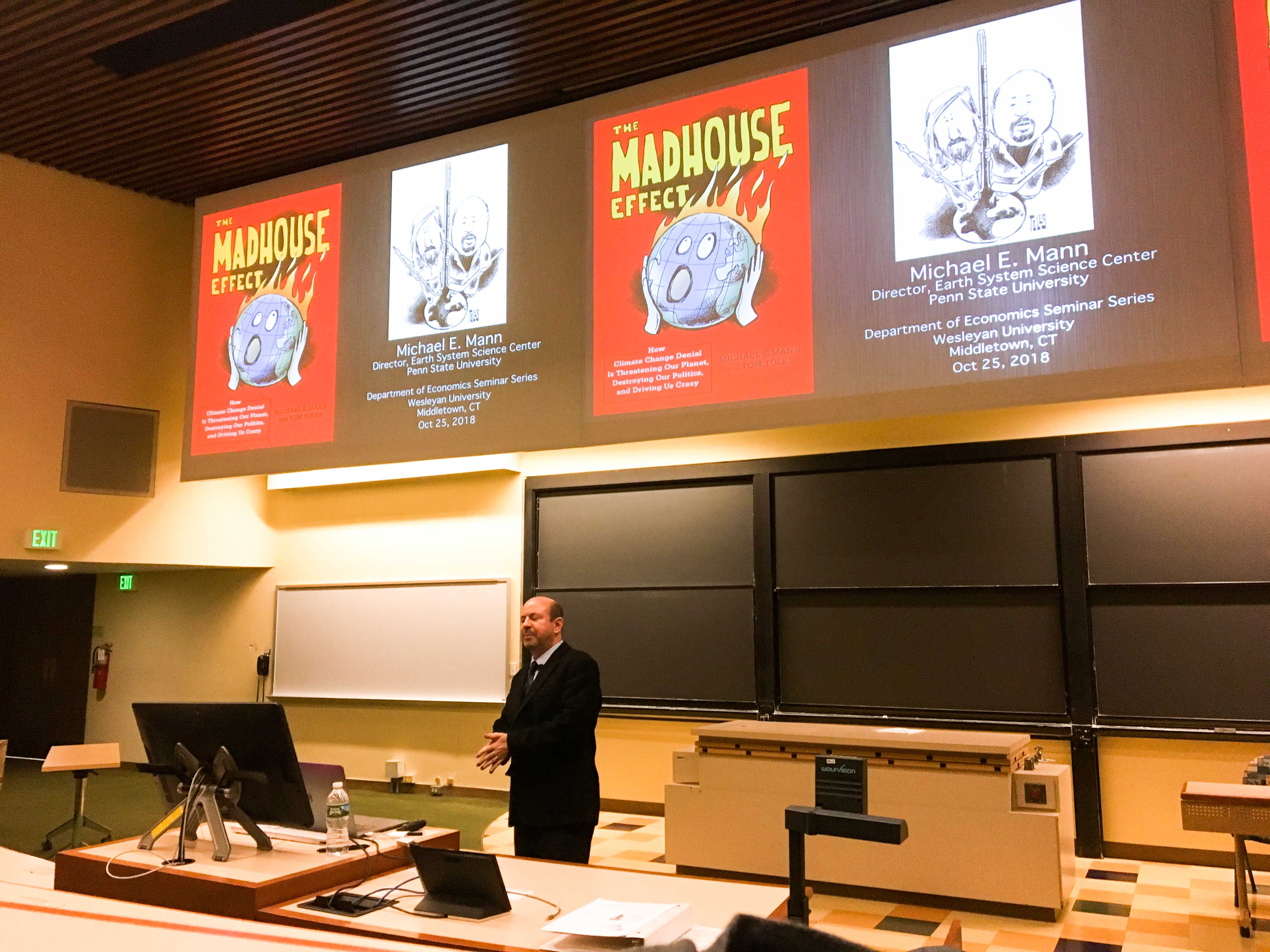

Dr. Michael E. Mann, Director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University, visited campus on Oct. 25 to deliver a lecture addressing climate change denial. The Department of Economics hosted this talk as a part of their fall seminar series.

Mann’s lecture followed the outline of his 2016 book about climate change denial titled “The Madhouse Effect,” which he co-authored with Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist Tom Toles. Mann noted that when he and Toles were working on the book, some climate scientists questioned the relevance of climate change denialism.

“We had colleagues who said at the time, ‘Why are you writing a book about climate change denial? We’re past that. We’re done with that. We’re moving on and are going to solve this problem and in the years ahead are going to be focused on solutions,’” Mann said.

However, the book’s topic became pertinent soon after its publication, with the 2016 election of President Donald Trump. This event induced a return to what Mann referred to as the “Madhouse effect” of climate change denialism, perhaps best represented by Trump’s infamous 2012 tweet asserting that the concept of global warming was fabricated by the Chinese as a tactic for making U.S. manufacturing less competitive.

“Some say that our book was prophetic because it indeed presaged a return into the madhouse of climate change denialism where we now do have a president who denies the basic science of climate change,” Mann said.

Mann continued to discuss how denialists have been granted a place in public discourse over matters like climate change.

“There’s this notion that those who reject the science of climate change are somehow skeptics, that they are somehow opposing the orthodoxy of the scientific community and that there’s something noble about that,” Mann said. “But simply rejecting mainstream science based on the flimsiest of arguments that don’t stand up to the slightest bit of scrutiny, that’s not legitimate scientific skepticism, it’s contrarianism or denialism.”

One by one, Mann refuted denialist arguments that aim to shroud climate science in uncertainty. These arguments included claims that climate change does not pose an imminent threat, that it may be self-correcting, and even that it is actually a good thing, which was a comment from former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency Scott Pruitt.

“We know humans have most flourished during times of what? Warming trends,” Pruitt said in February. “I think there are assumptions made that because the climate is warming, that that necessarily is a bad thing.”

The remainder of Mann’s talk emphasized just how patterns of climate change have and will continue to be detrimental to the planet. One consequence is a longer and more extreme hurricane season, exhibited by recent events like Hurricane Michael in October.

According to the Guardian, Michael was the first category four hurricane to make landfall on Florida’s panhandle, and came unusually late in the hurricane season (June 1 through Nov. 30) for such a large storm.

Mann characterized climate change as a threat multiplier. For instance, a direct consequence of climate change like a drought in Syria—likely the worst in the last 900 years—can lead to a ripple effect on other concerns like terrorism. Mann pointed to the fallacies in statements from politicians like Trump who insist we should not be distracted by issues like climate change and should instead focus on issues like international terrorism.

“That drought has created the conditions—the instability—to force rural farmers into the cities like Aleppo where they compete for food, water, and space with the people who live there,” Mann said. “More competition for fewer resources leads to conflict; conflict and instability creates an atmosphere where terrorist organizations can form.”

Mann also described his personal battles with climate change deniers. In 1998, Mann and two colleagues published a paper that reconstructed trends in the planet’s past temperatures and included a graph displaying this model. The graph, which The Atlantic called “the most controversial chart in science,” has been likened to a hockey stick because of the temperatures’ relative flatness for hundreds of years and then recent spike.

“It has become sort of an icon in the climate change debate because it tells a simple story,” Mann said. “You don’t have to understand the physics of the climate system or any of the nuances of the science to understand what this graph is telling us: There is something unprecedented happening today with our climate, and it probably has to do with us.”

The chart and Mann himself would go on to become targets of concerted efforts at discreditation. In the 2009 “Climategate” pseudo-scandal, emails between Mann and colleagues were hacked and combed through to extract pieces that could be used in claims that the scientists were attempting to hide declines in global temperatures. Then-Governor of Alaska Sarah Palin wrote an opinion piece in the Washington Post touting this argument.

“The email she was referring to was an email I had actually received,” Mann said. “It was in early 1999, on the heels of the warmest year we had ever seen…so scientists couldn’t have been talking about a decline in temperatures. Temperatures were increasing dramatically. Instead they were talking about some bad tree ring data that shouldn’t be used because they’re unreliable.”

Despite his numerous conflicts with climate change deniers, Mann retained an optimistic tone for the end of his lecture.

“I hope you will all vote in this upcoming election,” Mann said. “There is still an opportunity to act in time to avert catastrophic climate change, but we don’t have time to waste.”

Spencer Dean can be reached at srdean@wesleyan.edu.