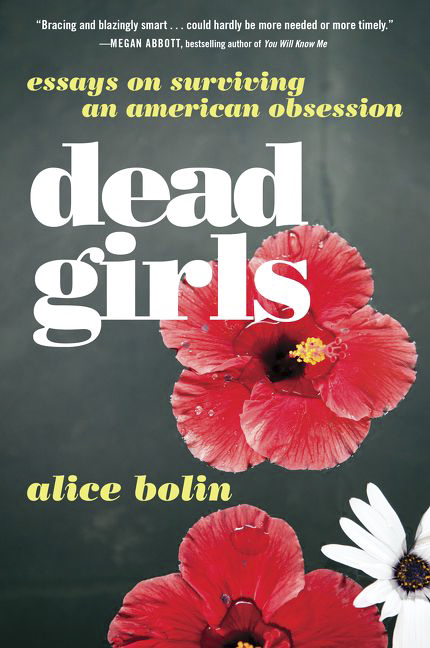

“I have tried to make something about women from stories that were always and only about men,” writes Alice Bolin in the introduction to her book, “Dead Girls: Surviving an American Obsession.”

The women at the heart of “Dead Girls”—a smart, mordant collection of essays released this past June—all belong to a very specific category. They pop up again and again, in movies, books, TV shows, and sometimes even on the news. They are often young, usually beautiful, and always dead. The Dead Girl is less a person than a victim, and her mysterious and violent end generally marks the beginning of the “real” story. Laura Palmer is a Dead Girl, and so is Lilly Kane. Hae Min Lee, the high school student whose murder is covered by the first season of Sarah Koenig’s smash hit investigative journalism podcast Serial, is a real-life Dead Girl. Bolin finds this fixation both troubling and fascinating, and her essays grapple with the allure and danger of female victimhood as a pop culture trope.

The defining quality of a Dead Girl is, paradoxically, her lack of any true defining qualities. After death, women are defined not by their own lives and personalities but by the impact their death has on the people—and particularly the men—around them.

As Bolin explains, “the Dead Girl is not a ‘character’ in the show, but rather, the memory of her is.”

A Dead Girl inevitably leaves in her wake a tangle of jealous lovers, protective relatives, and tormented, morally ambiguous investigators. These characters are all hallmarks of a Dead Girl show, and the girl herself only matters so long as she can continue to give these men meaning and narrative purpose.

“There can be no redemption for the Dead Girl,” writes Bolin. “But it is available to the person who is solving her murder…the victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.”

Bolin’s writing references an impressive variety of art and media, from the hardboiled detective fiction of the 1930s to the New Wave films of the 1960s to the reality TV of the mid-2000s. But “Dead Girls” is not purely a work of cultural criticism, it is also a personal account of Bolin’s own experiences. Several essays in the collection detail her move to Los Angeles and subsequent struggle to find herself in a new and unforgiving environment.

At first, these more personal essays seem disjointed from the main narrative of the book. Unlike the women she writes about, Bolin is alive and kicking (physically, if perhaps not emotionally). Yet as she describes her ongoing existential malaise—which leads her to visit famous L.A. cemeteries like Hollywood Forever and Forest Lawn and watch hours of true crime shows like Dateline and Forensic Files, which detail the gruesome murders of real-life Dead Girls—the connection starts to emerge. “Dead Girls” is not just a description of a cultural phenomenon. It is also a thoughtful reflection on the difficulties of existing as a whole, complex person in a society that seems to prefer its women quiet, passive, and ideally not even alive.

This loss of identity is not the only repercussion of this endless obsession with violence against women. When women are constantly presented as victims rather than people, this violence starts to seem like a pedestrian and even expected feature of modern society.

“Externalizing the impulse to prey on young women cleverly depicts it as both inevitable and beyond the control of men,” Bolin writes.

As Bolin is quick to note, this perception is particularly dangerous in a country where 73 percent of sexual assaults are committed by acquaintances of the victim and three women are killed by their partners every day. The impulse to prey on women is in no way beyond the control of men, yet it continues to be treated as an unfortunate but inescapable feature of modern life, a source of narrative intrigue rather than a trend that might be stopped.

“It’s clear we love the Dead Girl,” writes Bolin. “Enough to rehash and reproduce her story, to kill her again and again, but not enough to see a pattern. She is always singular, an anomaly, the juicy new mystery.”

Tara Joy can be reached at tjoy@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply