c/o: Steve Almond

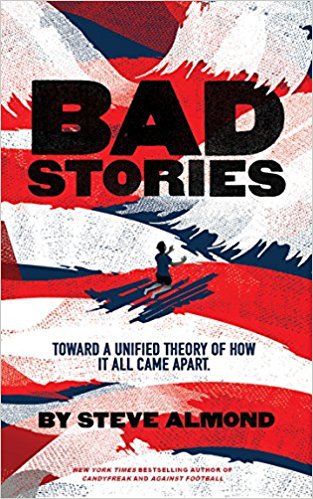

In his new book, “Bad Stories: What the Hell Just Happened to Our Country,” released by Red Hen Press on April 1, Steve Almond ’88 explores 17 of the most widely-circulated “bad stories” in the United States, tracing how these narratives have contributed to our current political climate. Almond, also a Kim-Frank Visiting Writer at the University, turns to popular culture, journalism and media institutions, political institutions, entertainment, the internet, and other storytelling venues and actors to examine how our stories and storytellers simultaneously target us as consumers and fail us as citizens. Through all of this, Almond invokes literature to help make sense of our country’s best and worst narrative tendencies.

Almond recently spoke to The Argus about the psychology of satire, the perils and pleasures of the Internet, and why he’s ultimately optimistic about our country’s future despite the seeming proliferation of divisive and delusional stories.

The Argus: You just published a book called “Bad Stories.” What is a bad story? What makes a story bad? And what are some themes that come up across these bad stories that you’re looking at in particular?

Steve Almond: Lots of people are walking [around] trying to figure out, “What the hell just happened?” So the reason that I am interested in trying to answer that question through bad stories is because there’s all this bad news about policies that [are] essentially making the rich richer, abdicating the rights of vulnerable communities, and [screwing] over a lot of people’s lives. It’s very easy to become fixed on that, disoriented by it, exhausted by it, cynical about it. I spent some time doing that, but because I’m not really a journalist—I may be a recovering journalist—and because I’m not a political scientist—I’m mostly a short story writer and a writer of nonfiction books—I have the tools to understand what’s going on in America best as a storyteller. And I think that makes sense, because that’s how human beings construct a version of reality, of their inner lives and their lives around them. They tell stories, and when those stories are good stories, when they are well-intentioned, when they are self-aware, when they are aimed at making us kinder and more merciful, more aware of the suffering of other people and our responsibility in some sense to end that suffering, I think they have good outcomes.

People who are inspired by the New Testament: go out and do good works in the world. They read that beautiful story, and they are made more human because of it. Or if you read a beautiful novel, I feel the same thing happens. Your moral imagination is enlarged, you become more compassionate, more human. If you listen to a speech or read the letters [from] Birmingham jail or James Baldwin’s writings, you are forced by their intellect and their compassion to be a more sensitive, caring person.

A: So, good stories motivate humanistic attitudes and behaviors, and bad stories somehow undermine those outcomes?

SA: What you see when you put your head into the news cycle is a maddening, exhausting blur of bad stories, and I want to step back and remind people, as I try to do in the book, [that] stories are powerful. In whatever form they are [in], they are a central way that human beings construct meaning. And there are a whole set of stories that are good and beautiful and that have allowed this species to do really wonderful things. And then, unfortunately, there is another kind of story, a bad story, which I would define as a story that is wishful—a wishful story that has a good idea to it but is ultimately fraudulent. Sometimes it is a story that is consciously designed to plug into people’s primal, negative emotions; to sow discord; to cast out of ourselves a certain kind of ugliness and throw it on somebody else. And sometimes they’re propagandistic, that is, there is a profit motive attached to telling a story that will gather attention for yourself or that will keep the sponsors’ attention by plugging into people’s grievance, their frustration, their rage, their self-hatred. Those stories always have a bad outcome. And all of that led us to elect somebody of astonishingly low character and dubious qualifications. That outcome was driven by a whole set of bad stories that Americans have been telling themselves and each other or consenting to for longer than there’s even been an America.

Sometimes bad stories are told out of psychological necessity. Those of us who love watching Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert or any of these other political parody shows, we’re not sitting there watching those because we want to effect evil in the world or justify our own darkness or anything. We’re trying to escape from a painful reality that our traditional civic institutions like media and our political theater are dysfunctional and broken, and they don’t even try to solve people’s problems anymore. That’s really both enraging and heartbreaking, so one of the things we do for relief is look to comedians who will convert that anguish into disposable laughter. Is there a negative intention there? No, but there’s an avoidant one. That energy, that distress is actually necessary. Every time the United States has made more progress, it’s because people have been outraged and anguished and upset, and they have become politically engaged.

A: Speaking about entertainment more broadly, can you explicate some of the intersections of entertainment and politics as of late?

SA: Oh my god! It is constantly happening. It’s the air around us. Every time you turn on cable television or go on to a website or even go onto Facebook, and you have a complicated problem that needs to be solved like criminal justice reform or immigration or inequality in wealth or climate change—these big serious problems that threaten not just our democracy but the entire species—when they are turned into a comedy bit or they’re turned into a kind of binary brawl where pundits are yelling at one another, that [scene] is very far from the realm of actual civic engagement and problem-solving. [That’s] the realm of entertainment. The central argument that Neil Postman was making [in his book “Amusing Ourselves to Death”] was that America is doomed if it cannot have a serious discourse about the problems that it faces. It seems to me that Trump was a stress test for that.

A: There’s a whole section in your book about the Internet. Could you speak a little bit about that?

SA: Well, as with the media, we’ve met the enemy and it’s us. I [might] complain about those pundits arguing on TV or these corporations that just want to present us with entertainment, but the reason they do that is because we watch. It ultimately redounds to us. It’s not the media’s fault, it’s our consumption of entertainment rather than substantive reporting and journalism. By the same token, the Internet is just a tool, what we do with [it] is up to us. The kids in Parkland use the Internet to try to tell better stories. That’s a fantastic use of that tool, to try to combat the fraudulent, propagandistic stories told by the gun lobby, the gun manufacturers, people who stand to profit from the more people buy guns, and I thought it was beautiful and inspiring to see that.

[At the same time], we’ve decided to use [the Internet] to contend with our feelings of isolation and helplessness and the desire that we feel for attention and regard from the world. I think people have figured out that this tool is incredibly politically powerful. What Cambridge Analytica realized [was that] if people live on their devices, [the Internet] is a very efficient way to tap into their primal, negative emotions.

For instance, I had a young friend during the election who was a Bernie supporter. He was talking a lot about economic justice and income inequality. But then he was [exposed to stories] that got underneath that message of social justice to the parts of [him] that were grieved and felt left out of the economy. [He] was fed the kinds of stories that converted those feelings into hatred of Hillary Clinton, and he stopped posting about environmental causes and social justice. I saw right before my eyes someone who went from telling good stories and trying to aim at a good outcome to telling really corrosive, bad stories.

A: Thanks for sharing those fun views with us!

SA: Very uplifting, isn’t it? But there are also lots of examples like [the Parkland students’ activism]. I did an event last night in Portland with this 25-year-old guy who is a state representative, and he just submitted a bill to ban conversion therapy. You know why he’s a state representative? He went to school in Maine, and he looked up one day and there was a leak. The classrooms were literally falling apart. He had a younger sister who was coming into this school, and he became active trying to pass a referendum that would fund a rebuild of that high school. That [experience] got him involved in politics. That’s an amazing story. We don’t hear enough of that kind of story. It’s always so cynical. This guy is a real warrior for good government and solving small problems and appreciably improving people’s lives. We almost never hear that kind of story, but it’s out there. There are a lot of people who want to do good and want wealth to be distributed more fairly and live up to that ideal of America as a place of equal opportunity. I think we’re in the majority. We need to get off our asses and do something like that.

This interview has beenedited for length and clarity.

Camille De Beus can be reached at cdebeus@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @cdebeus.

Matt Wallock can be reached at mwallock@wesleyan.edu.