A Clairvoyant in Connecticut: How Leland Stowe Forecasted a Second World War

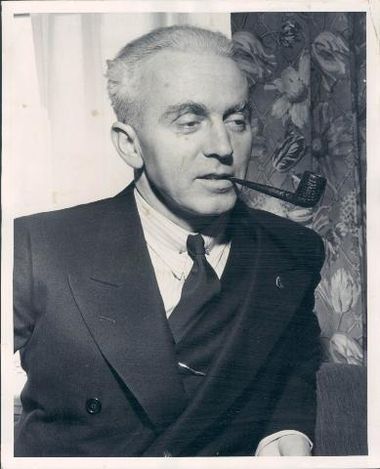

Leland Stowe, class of 1921, was already a Pulitzer Prize winner when he returned from Germany in late 1933. If any American was credible and qualified to write on early Nazi Germany, it was Stowe, who at just 33 years old already had built a strong pedigree of reporting on interwar Europe. So when Stowe laid bare his fears over what he saw in Germany in his 1934 work “Nazi Means War,” the public should have taken him more seriously.

Stowe had built an impressive following as Paris Correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, largely on the strength of his coverage of the Paris Reparations Conference—his Pulitzer-winning work. The accords were particularly friendly toward Germany, piquing Stowe’s interest. When Weimar Germany began its industrial boom and appeared to be primed for expansion, Stowe’s concern propelled him into the belly of the beast. He spent the summer and fall of 1933 traveling through Germany, hoping to assess the extent to which Hitler and the Party were preparing for war.

His experiences agitated and disturbed him. Upon returning to the United States, he immediately began work collecting his thoughts and recounting his time. This eventually turned into “Nazi Means War,” which contains not just casual observations of life in Germany, but also in-depth access to Chancellor Adolf Hitler, highlighting the difference between his public and private faces.

“Germany wants nothing but peace,” Hitler claims in the first direct quote that Stowe recounts. “More than anybody else National Socialist Germany clings to peace because the National Socialist idea is based on a radical concept of state leaders united by blood. It turns towards domestic issues and therefore knows no imperialistic policy of conquest toward the outside.”

Of this assertion Stowe was, to say the least, skeptical. The remainder of his tale and his argument, beautifully intertwined, take aim at Hitler’s claim. To prove his point, he alternates between cold, deductive logic and vivid, often frightening, imagery with a high degree of intentionality and calculation.

“Important as facts are, it is essential to feel the surging crescendo of the National Socialist spirit in Germany before you can be prepared to examine the physical forces which lie behind that spirit,” Stowe writes. “It is necessary that the colors of the picture should not be overlooked.”

He presents to the reader a confluence of events—centralized government power, military rearmament, extreme nationalism, indoctrination, punishment for dissenters, the glorification of ethnic growth, and much more—that he concludes is not just likely to result in war, but rather is a quite purposeful preparation for war. By the end of the book, war is no longer a prospect: it is an inevitability.

He turns his attention to the responsibility borne by his own country in his final chapter, “If War, What About America?” The tone of the chapter is a bit of a jumbled, capricious mix of ideological isolationism and a fear-induced call for some sort of intervention. Stowe certainly understood the potentially calamitous size of the impending war and felt strongly that the Nazis should not be allowed to continue unimpeded.

“It is outside the province of an American foreign correspondent to attempt to formulate definite policies or to offer positive solutions,” he hedges toward the end of his tale. “But one cannot walk in the midst of a Herculean code of military conduct, one cannot see war-in-the-making on an unprecedented and almost terrifying scope, without pondering what this creature from Mars may one day mean to his own people. If man is to live he must ask himself what can be done—what can America do?”

Readers in 2018 may be impressed by Stowe’s prescience. Readers in 1934, tragically, were not. As the first writer to document the full extent of Germany’s ever-accelerating militarization, the mere physical observations of Stowe’s trip were tough to swallow for American readers. Stowe’s deductions from those observations, not to mention his call to action, likely put his audience over the edge from skepticism to steadfast denial. “Nazi Means War,” essentially, was ignored. He first attempted to publish the work in the Herald as a series of articles, but was rejected, as the paper was rightfully concerned with the prospect of the piece earning a poor reception. When Stowe’s work was eventually published as a book, his critics dismissed the story and labeled Stowe as alarmist. “Nazi Means War” quickly fell out of the public consciousness.

By 1940, Stowe was something of a household name. His World War II reporting had earned him worldwide eminence, and he nearly won another Pulitzer (earning a controversial second place) for investigating the German invasion of Norway and unveiling a wide espionage web of Norwegian traitors. But his interwar Germany reporting—in hindsight, probably his most impressive work—was swept under the rug. His story serves as a reminder that sometimes, the stories that nobody wants to hear are the ones that most need to be told.

Sam Prescott can be reached at sprescott01@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply