Wesleyan Students for Ending Mass Incarceration (SEMI) held an hours-long sit-in and rally at the Office of Admission to protest the University’s mandatory “box” on the Common Application. The “box” requires applicants to indicate whether or not they have been convicted of a crime. The demonstration culminated in a conversation with President Michael Roth ’78, who agreed to meet with student organizers within the next 10 days.

The sit-in and rally, held on Friday, April 13, coincided with WesFest, the University’s annual open house for admitted students.

“What we’re demanding is a commitment to ban the box, and a promise that the members of Students for Ending Mass Incarceration are going to be involved in the process for creating that institutional change,” said Noah Kline ’21, one of the protest’s coordinators. “We have gone through every institutional pathway. Every time the University has told us, ‘We’re gonna look into this. We’re gonna talk to you in a bit.’ This is a tactic that the administration uses to slow down student activism.”

The Ban the Box movement, which began gaining traction in 2006, advocates for the Common Application to no longer require applicants to disclose the information relating to their criminal histories. SEMI has garnered support for the movement through meeting with student, faculty and administrative groups on campus. Last fall, the group also circulated a petition to ban the box, which amassed over 300 signatories. Still, little administrative headway has been made.

“A core belief of SEMI is that no one is disposable, and [the box also] targets people who have been convicted of violent crimes,” said protest coordinator Angel Martin ’19. “They should still have a right to apply for higher education and access to higher education because that is going to help with their reentry process and reduce recidivism rates.”

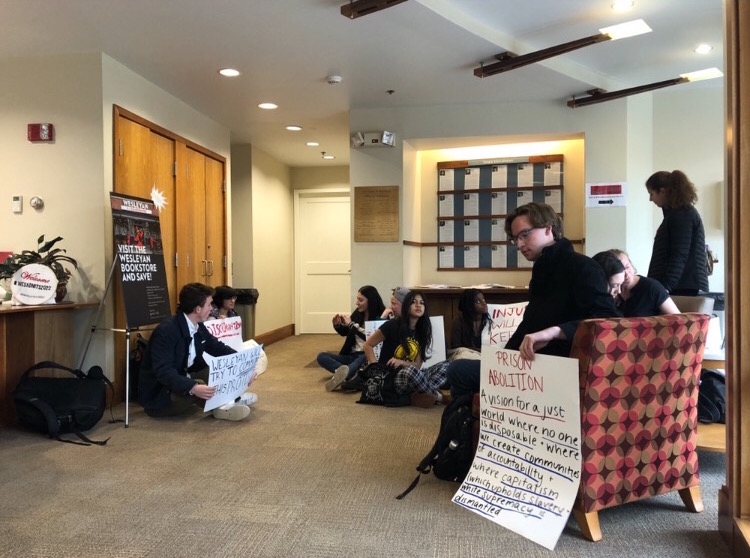

Starting at around 9 a.m., over 20 activists and members of SEMI held a sit-in in the Office of Admission, which lasted for almost 3 hours.

“This is timely,” Dean of Admission and Financial Aid Nancy Hargrave Meislahn said to the protesters about an hour into the sit-in. “We need to make a decision as a University on this pretty much within the month of May. What I will commit to is I will look at the research you send. I will have a conversation with President Roth.”

Protesters expressed frustration over the evasive nature of her response and continued with the demonstration.

Over 50 activists gathered for a rally outside of the Office of Admission at 1 p.m. Participants then crossed Wyllys Avenue and began walking toward the Usdan University Center. In front of Fayerweather, the crowd intercepted Roth, who was walking toward Andrus Field. Protest coordinators read aloud their list of demands and asked him to commit to banning the box.

“We will keep demanding, and we will keep rallying, and we will keep yelling until this University agrees to remove the box from all its applications,” Kline said to Roth. “That means we want a commitment to banning the box, to ending any intrusive questions about people’s disciplinary history.”

“We are looking for ways—not to get rid of all, what you call, ‘intrusive questions’—but to make sure that our questions don’t discriminate against formerly incarcerated people,” Roth responded.

After a brief back-and-forth, Roth began walking away, and the protesters followed, chanting, “Ban the box.” Roth went through Usdan, crossed Wyllys Avenue, and sat outside of Crowell Concert Hall. The crowd stood around him, spilling into Jackson Field, and a dialogue ensued.

“I don’t think I would ever be willing to say to prospective students that we are not interested in whether you have a history of violent crime or behavior—I’m not willing to do that,” Roth said. “I do take seriously [that] by asking this question in a certain way, we are participating in a system that is inherently discriminatory.”

Roth explained that he has asked the Office of Admission to work with Slate, a web platform that aggregates colleges’ admissions data, to propose a new method of acquiring applicants’ histories of violent behavior or lack thereof. Roth said that they expect a response from Slate within the next three weeks, which many students pointed out was close to the end of the school year.

“That’s the pattern: the institution partially agrees and tries to placate us and then takes a lot of time so we lose momentum,” Martin later said.

Organizers asked to be included in a conversation within the next seven days about Ban the Box. Upon further discussion, Roth agreed to meet with them in the next 10 days.

The Argus spoke with the protest coordinators following the rally.

“Maintaining some structure of the questions still disproportionately targets people who either have committed what you have called ‘violent crimes’ or those who have been called violent because…they were witnesses or near [to] violent crimes,” protest coordinator Lola Makombo ’20 said. “I don’t think that there’s any way in which we can distinguish the two.”

Another protest coordinator, Fran Woodbridge ’20, also addressed the Center for Prison Education (CPE), which just received a $1 million grant to expand its efforts in educating incarcerated inmates.

“Wesleyan has very much branded itself as a university committed to fighting mass incarceration,” Woodbridge said. “The thing about CPE is that Michael Roth, he’s committed to educating people while they’re in prison, but once they come out, then they are disposable…. That is something that he also needs to answer about.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article suggested in a quote that only violent crime convictions have to be reported when checking the “box,” when, in fact, the “box” asks about any criminal record.

Claudia Stagoff-Belfort contributed to this reporting.

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @HannahEReale.

Emmet Teran can be reached at eteran@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @ETerannosaurus.

Leave a Reply