c/o nytimes.com

On June 6, 1990, Nick Haddad, member of the class of 1992, the chief perpetrator in the firebombing of President William Chace’s office, would be shot and killed by two drug dealers employed by Haddad as part of a drug ring that he organized. The murder came four days after the University’s Board of Trustees had officially decided to divest entirely from all companies doing business in South Africa, an initiative to which Haddad had devoted his short-lived political activism career at Wesleyan. Of the students and professors that knew Haddad well and attended his funeral later that month, all would be shocked to see his mother there, who Haddad had claimed was killed in Sudan, not to mention the discovery that Haddad had grown up a Catholic in Willimantic, Conn. with Middle-Eastern roots, instead of a Black Muslim from Lebanon. Haddad, as it turned out, had lied about his identity to even his closest friends, offering false and contradictory accounts of his past. Kofi Taha, also a member of the class of 1992, often associated with Haddad as the second half of the radical activist duo on campus, would not be in attendance.

The mystique surrounding Haddad and his ambiguous relationship with Taha permeates the story of the University in the 1989-1990 school year and presents a multi-faceted depiction of the motivating factors behind student radicalism during the era. Intertwined with the events that transpired during the period, this second installment of Wes Docs will profile Kofi Taha and the identity crises that motivated his political disaffection.

While Taha and Haddad disagreed about tactics for agitation against the administration on several occasions, they were widely recognized as the two chief campus activists and the faces of the Apartheid Divestment movement. They were the co-editors-in-chief for The Ankh, along with another publication that they started together, The Afrikan Nation, publishing criticism of administration from the Black separatist perspective. Any protest or political action taken up by students during that year was presumed to be organized by the two.

Taha’s political activism, however, channeled a deep-seated resentment toward authority based on past experiences, manifesting in a political vision that diverged from Haddad’s. Haddad, it appears, had his own set of frustrations that verged more on an existential struggle to find his place in the world.

Taha, who is mixed race, grew up in the Bronx in a politically active family who focused on reforms in their local community where many people in the neighborhood struggled to pay the bills. He chose to attend Wesleyan after his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and wanted to stay close to home so he could help her out on weekends. A series of racially motivated acts of violence in the New York area were fresh in Taha’s mind when he returned to the University as a sophomore.

“Kofi was a mixed race guy like me and at a place like Wesleyan, especially for mixed race people, you’re always faced with a stark choice,” explained Peter Paris ‘92, one of Taha’s classmates and friends, in Caroline Fox’s 2012 senior thesis “An Adversarial Place: The 1989-1990 Academic Year at Wesleyan University.” “You either have to be with the black community or the black community would kind of reject you. And I think that a lot of us took that and kind of went a little overboard on it. Malcolm X dichotomy versus the King dichotomy of political activists on campus. Malcolm X-type guys would do something whereas others would just sit around and talk about it or try to work within the system and be naïve in that way.”

At a time when Malcolm X was undergoing a national revival in Black thought, the political philosophy that came out of Nation of Islam and Black separatism defined Taha’s political outlook during his years at the University and inspired him to export his own brand of Black nationalism onto campus. Malcolm X House, where Taha lived, became the epicenter of radical activity on campus; it had symbolic resonance for Black Wesleyan students to carry on the torch of the Vanguard Class of 1969, the first fully integrated class in Wesleyan’s history that fought for the establishment of the house’s name.

The inauguration of President Chace became a defining moment for Taha’s activism on campus and exemplified his combination of theory and practice. To protest Chace’s continued support for the school’s ineffective divestment policy, five radical students were planning to either kidnap the president, handcuff him to the podium during his inaugural speech, or handcuff themselves to the podium. Once Taha got involved, he immediately rejected this plan.

“It was clear to me that this was a perfect example of how message was going to be overshadowed by method,” recalled Taha in an interview with Fox for her senior thesis. “I said, ‘Why don’t we write down what it is we want? What is it that we feel like the president is coming here to do?’”

Persuaded by Taha, the students ended up handing the president a letter in the middle of his speech that demanded, along with divestment, that the University upgrade the African American Studies Program to a department and increase the number of faculty members of color on campus.

While the students’ effort received mixed reactions and didn’t result in any tangible reform, it demonstrated Taha’s intentions to transcend radicalism for radicalism’s sake. He had an agenda—a point that would separate Taha from Haddad. While Taha was certainly mobilizing the divestment movement on campus, spearheading the protests against South African parliament member Helen Suzman’s lecture on campus, he focused on an array of racial issues on campus as well.

“Taha was frustrated that the gains of previous generations of activists – including the Vanguard Class of 1969 – did not seem to be valued at Wesleyan,” wrote Fox in her senior thesis. “African-American Studies, which first began to offer an academic major in 1983, remained an academic Program in 1989, as it had been since its creation. Unlike full-fledged academic departments, it faced limits on its influence in the hiring and promotion of faculty. Furthermore, in the two years prior to the 1989-1990 academic year, Wesleyan had experienced a mass-exodus of black faculty. Six of eleven of Wesleyan’s African-American tenured or tenure-track faculty left the University between 1988 and 1990. Four faculty members resigned and one died. One, the political scientist Jerry Watts, was denied tenure, twice.”

In his attempts to fit himself into the tradition of civil rights activism, Taha latched himself onto the case of Jerry Watts’ tenure. Professor Watts had been denied tenure in 1980 but after protests was given a two-year contract. In April of 1990, Watts announced that he would be leaving Wesleyan in protest due to the disrespect that he felt he received from the University. Watts explicitly stated that his decision was motivated by racial injustices. In response, Taha wrote a scathing article in The Argus that excoriated the University for ignoring the needs of Black professors and not investing enough into the African American Studies Program.

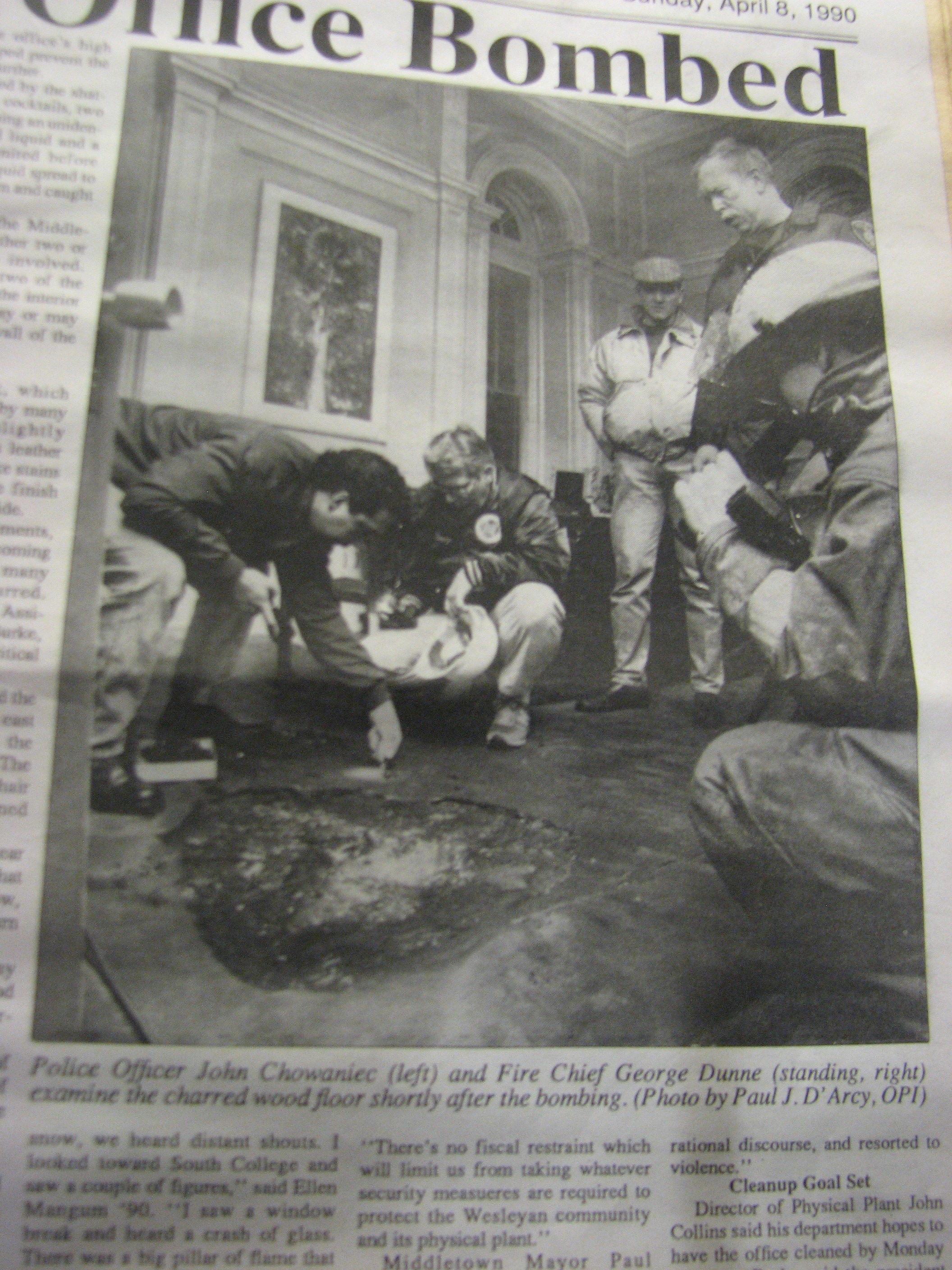

While Taha began discussing a tempered course of action with other activists, Haddad took a drastically different approach. It was no coincidence that Watts’ resignation came a week before the firebombing.

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lwgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.

-

Kofi Taha