Among the U.S. Fortune 500 companies, a ranked list of businesses with the largest total revenues each year, 32 Chief Executive Officers were women. The statistic is published each June by Fortune Magazine, and since its publication of their 2017 list, the number of female CEOs has shrunk by 6 to a current total of 26. For those of you who can count out futures as a CPA or CFO, this means that only 6.4 percent of Fortune 500 companies, now down to a measly 5.4 percent, have women as CEOs. In a span of fewer than eight months, that’s an 18.75 percent decrease in the number of female CEOs heading the world’s 500 largest companies. To put that drop in context, when the Dow Industrial Average fell 4.8 percent on Monday, the largest point decline in the blue-chip index history within a day, NPR reported that, faced with a 4.8 percent decline, “the damage could be substantial to the collective investor psyche.” Fortune claimed that this drop made “the ticker tape look even uglier than it did on the darkest days following Lehman Brothers’ 2008 collapse,” and the Washington Post called it “heart-stopping.”

When the Dow drops 4.8 percent in a day, Wall Street workers are abuzz with fear and cynicism. Yet, barely a shudder ripples through trading rooms as the proportion of female Fortune 500 CEOs drops 15.6 percent from an all-time high in about seven months. Then again, a day without a woman in the boardroom is nothing shocking. A day without a woman in the boardroom is, well, just the kind of day we are used to.

The fact that women are still few and far between in the corporate and technological worlds is far from a novel complaint, and its post-Harvey Weinstein hype continues to (re)thrust gendered workplace dynamics into the public spotlight. I mention these numbers, not to position this piece in the broader realm of literature dealing with women’s historical barriers to entering corporate hierarchies, but rather to situate the “Dorito” issue in the current context of our national dialogue about female progress and its modern obstacles.

While once a podcast that easily made the top 10 each week, Freakonomics has been traded in for newer and hipper shows due to an increasingly crowded podcast market and narrowing listener demographic. Resting at an average of 26 for the majority of the last 2 years, listeners have flocked from Freakonomics to podcasts like Kickass News and Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations—the equivalent of ditching a nerdy economics professor to join a master in Javanese Gamelan.

Freakonomics, a show conducting jargon-limited explorations of behavioral economics, has been conducting an interesting series about CEOs. The show has secured a variety of interviews with high-performing and well-known executives ranging from Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook to David Rubenstein of the behemoth private equity firm the Carlyle Group. The past two episodes in the series have progressed with little controversy, and Freakonomics has maintained its constant high-20s ranking on the iTunes top Podcast chart. On Tuesday, Feb. 1, Freakonomics aired the series’s third episode, “I Wasn’t Stupid Enough to Say This Could Be Done Overnight.” The episode features Indra Nooyi, the current CEO of PepsiCo, the world’s second-largest food and beverage company, who is frequently cited as one of the world’s most influential people and most powerful women. In addition to captaining a $62.8 billion enterprise through the 2008 financial crisis and beyond, Nooyi, an Indian immigrant, has also been married for 37 years and raised two daughters.

Her interview with Freakonomics was demonstrative of the many ways in which Nooyi represents the ideal professional mentor: She is humble yet aware of her successes, clearly open-minded but thoughtfully principled, blunt and logical in her approach to management but emotionally open in discussing personal and global challenges. Yet, in the hour-long discussion she has with Stephen Dubner of Freakonomics, the public does not pick up on the story she tells about her innovation at Tropicana (a PepsiCo brand) to extract the fiber from the orange’s pulp in order to reduce waste and improve the drink’s nutritional value in a place no one had ever thought to look. Twitter was not bursting at its seams to laud her sacrifices in the name of increasing female C-suite presence: “In any industry, in any profession, in any part of society, trend-setters went through this sort of scrutiny, and criticism, and commentary. I think this group of women C.E.O.s, all of us are going through that right now.”

Instead, the internet picks up on an off-handed comment about the intensive research and development process that she oversees at PepsiCo. Rather than supporting a woman who embodies the very change we are hoping to see at the top, her comment gets taken out of context, and she is shunned by women in the name of the very cause she is championing daily. This is not to say that, taken out of context, the idea and propagation of increasingly gendered products can reinforce cultural norms or stereotypes that women have a right to resent. However, in the context of the interview, Nooyi was using the example of how women and men tend to behave differently when eating chips out of a bag—a fact that their research department has likely discovered through hundreds of hours of ethnographic study. The suggestion is not to advertise a newly differentiated product, but to emphasize the way in which gender norms infiltrate everyday practices that she, as the leader of a food company, has decided not to ignore.

Those who took the time to listen to the episode, or read the transcript, would have noticed an important caveat of the so-dubbed “Lady Doritos” she described: Nooyi says, “[Young men] lick their fingers with great glee, and when they reach the bottom of the bag they pour the little broken pieces into their mouth, because they don’t want to lose that taste of the flavor…. Women would love to do the same, but they don’t.” The essence of what she is describing is not inherently sexist and not an attempt to say, as one Twitter user put it, “Good news, ladies. We got a female Colonel Sanders and Doritos that don’t crunch, so feminism is cancelled. We’ve achieved equality.”

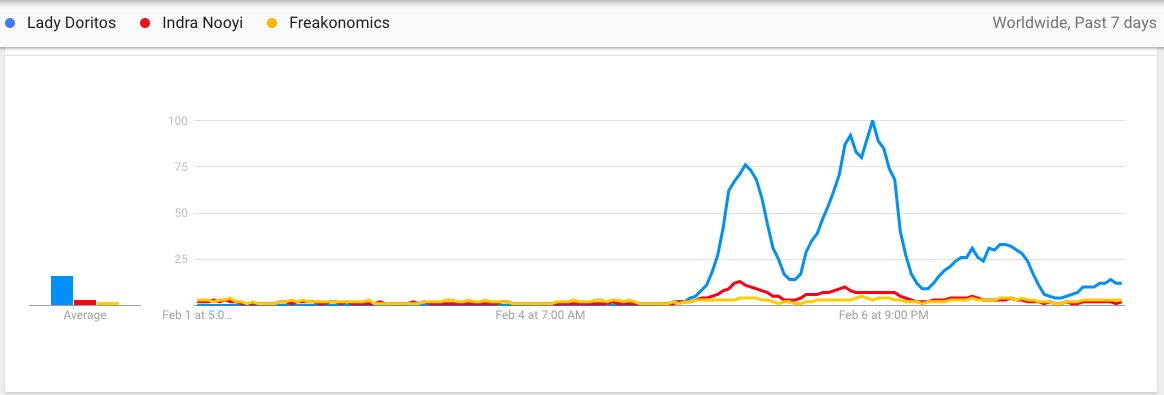

The sad reality of this “Lady Doritos Debacle,” which “did not go over well on the internet” because “even female CEOs pitch bad ideas like Lady Doritos” is that while “Lady Doritos” became a trending hashtag and Buzzfeed clickbait, the actually relevant and truly interesting interview material with one of the most successful and well-spoken businesswomen of our time got completely overlooked. Google Trends, which analyzes the volume of a given search term either on its own or relative to other specified searches, shows a huge spike in searches for “Lady Doritos” and “Women Chips” over the past week while revealing barely perceptible, possibly statistically insignificant increases in searches for Freakonomics and Indra Nooyi (see graph above). It seems that not many people seemed all too interested in listening to the podcast itself or hearing the inspiring things Nooyi herself offers. In fact, the episode ranks 121 in popular iTunes podcasts, right below a fascinating-sounding episode of The Dave Ramsey Show titled “I’m in Debt and Want to Cash-Flow Medical School (Hour 3).”

The story here should not have been about Fritos for women or Doritos for men or pita chips for anyone on any part of the spectrum. What matters is the way in which we, as listeners and supporters of a global business environment in which women compromise a more equal share of leadership roles, engage with the pioneers who are leading the way. In the same interview, Nooyi discusses one of the many challenges she faces as a female CEO: “When you become a C.E.O. and you’re a woman you are looked at differently. Whatever you say people do—they say things like, ‘Well a guy C.E.O. wouldn’t have said that. Or a guy would have said it differently.’” Internet users are quick to dissect female leaders on the basis of isolated quotes, holding them to the same impossible standards that make it difficult for women to occupy executive offices in the first place. These standards make failure for women leaders inevitable, and that’s ultimately bad business for everyone. Instead, take the chip(s) off your shoulder, and help lead the charge in listening with more empathy and expanding our attention to include the bigger picture.

Emma Solomon is a member of the Class of 2018. Emma can be reached at ebsolomon@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply