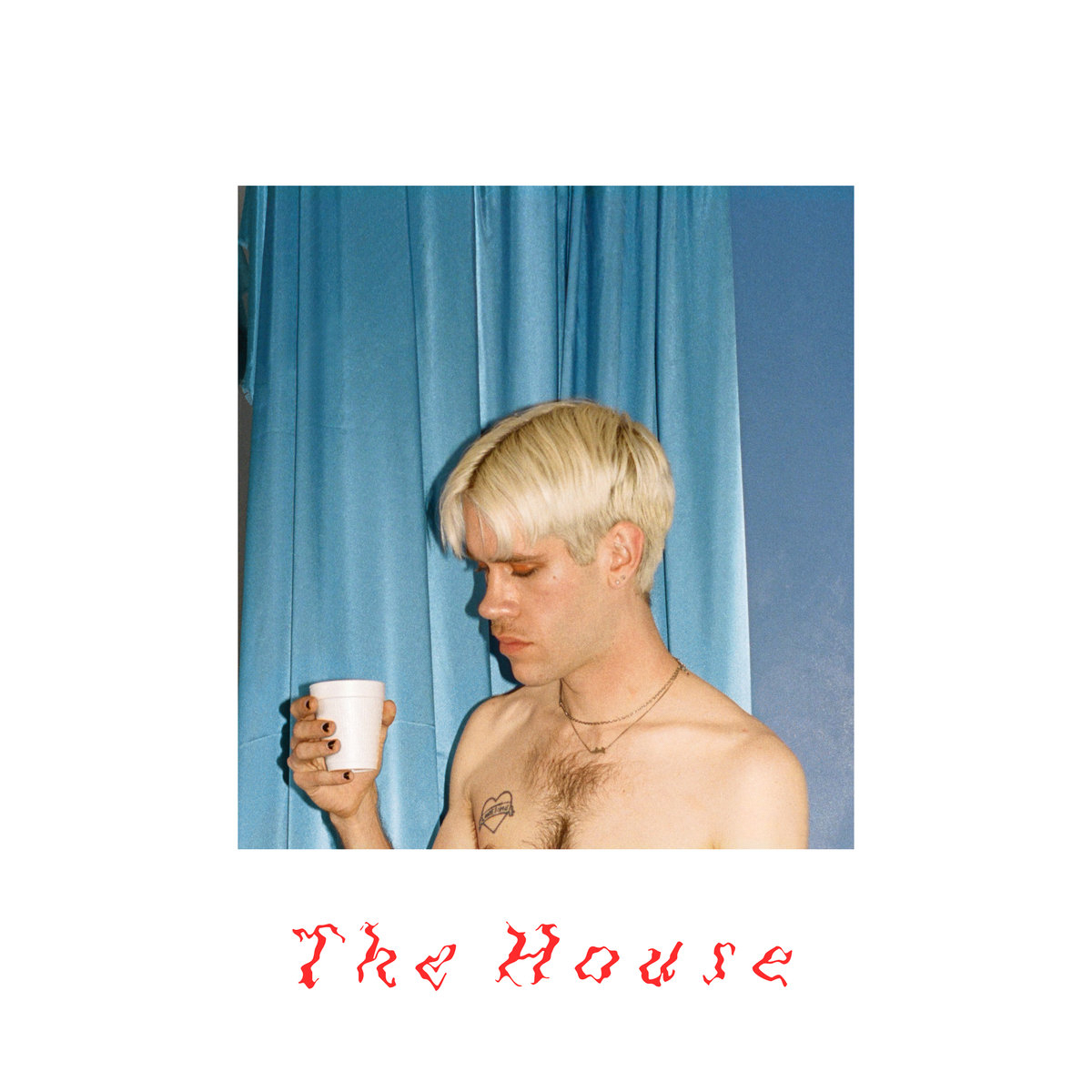

c/o bandcamp.com

Porches released its third album, The House, on Friday, Jan. 19 via Domino Recording Company. At 14 tracks, The House is Porches’ most varied album to date, combining chillwave, synth-rock, R&B, bedroom pop, and other influences. It is an uncertain but compelling foray into the realm of synth-dance, reflecting the continued musical evolution of Porches’ frontman Aaron Maine.

This blend of styles is unsurprising, especially given that Maine collaborated with Alexander Giannascoli of (Sandy) Alex G, Dev Hynes of Blood Orange, Maya Laner of True Blue, and others. Furthermore, The House was produced by Chris Coady, who has worked with everyone from Beach House (including Thank Your Lucky Stars and Depression Cherry), the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Grizzly Bear, and Santigold, to smaller but influential alternative rock and dance projects (see Lemonade, Architecture in Helsinki, and Delorean, just to name a few). He also worked on Porches’ previous album, Pool. Coady’s sensibility comes through in both albums’ clean mixing, spacious arrangements, and careful sequencing. He tends to treat vocals like a supplementary instrument, gently pushing them behind or on top of keyboards, synths, and strings. Under Coady’s influence, vocals can wash into and out of songs, crashing and receding like waves.

The House showcases Maine’s commitment to experimentation, but this experimentation feels tempered or controlled. Like Archy Marshall of King Krule or Trevor Powers of Youth Lagoon, Maine relies heavily on voice manipulation to express emotion. His tool of choice in The House is auto-tuned, but his use of this tool is largely unoriginal and flat—a kind of hipster recasting of mid-2000s T-Pain. The auto-tune is most successful when it is applied to nearly-spoken lyrics, such as those of the minute-long interlude “Understanding,” which was written by Maine’s father Peter. Here the auto-tune sounds sincere and disarming, a method of accessing an emotional register that is otherwise unattainable.

Where Archy Marshall goes for breadth, Maine goes for depth or, at least, focus. He is content working with a more limited palette, slowing down, and breathing. He makes a case for a blank space in his music, which we can also see in his album covers, all of which feature centered images or graphics with generous white borders around them. As in his music, these borders do a lot of work: they structure, format, and frame. They are architectural elements that invite the listener into a particular environment or space. Hence the haunting, consuming, and expansive atmosphere of “Country”, one of the album’s singles and best songs. “Country” also has an understated music video featuring a sad white boy (Maine) in a truck bed, for those into understated music videos featuring sad white boys in truck beds.

c/o bandcamp.com

The album’s other single, “Find Me”, bounces inside the safe parameters of familiar, vaguely house-inspired movements. Its momentum is shallow and catchy; it lacks the depth of feeling that many of the album’s songs contain. For example, “Ono” is a deceptively simple ode to escapism that benefits from its reliance on repetition (the chorus is literally just the refrain “oh no” repeated four times). When Maine sings, “Got so wet / inside my dreams / if I could stay / I’d do most anything,” his directness is cleansing. It washes over the synth in the foreground.

“W Longing” pulls from chillwave, R&B, and bedroom pop lineages. The synth evokes early Washed Out or Nosaj Thing. While the vocals call to mind Blood Orange, the arrangement remains sparse. The same could be said of the album’s last song, “Anything U Want”, which, like “Understanding”, embraces auto-tune as a tactic to access a specific songwriting terrain: in this case, it’s the line, “I love you.” Is it tacky to describe an auto-tuned “I love you” at the end of an indie rock album released in 2018 as delicate or vulnerable or charming? Somehow, this “I love you” is all three.

“Goodbye” combines many of Maine’s best musical impulses. The song opens economically with low keyboard notes, then vocals and synth come in. It escalates into a Dan Deacon-esque dance track, looping over itself with slight variations. Like “Find Me”, it has a strong arc, building toward a confident, almost trancelike longing before suddenly deconstructing itself. It comes to an abrupt stop that highlights the intensity achieved just seconds earlier. All of this transpires in less than three minutes. Again, simple songwriting has the effect of washing over the sounds on which it is held up.

“Into a light / That I once knew / I swam deep / And thought of you,” Maine sings.

Images and sensations of submersion resurface throughout the album—the next song is aptly titled “Swimming.”

Porches has evolved considerably since the release of its first album, Slow Dance in the Cosmos in 2013. Early on members of Porches were regular collaborators with Greta Kline and her project Frankie Cosmos, with whom they also toured extensively (including a packed show at The-Building-Formerly-Known-As-Eclectic). By the time Porches released its second album, Pool, in 2016, it had made a name for itself in New York’s dream pop scene. With The House, it has pushed further into that dream pop sound while staying open to other influences and styles. Aaron Maine has always been at the helm of Porches, and it is his own expansiveness that keeps Porches dynamic.

Not entirely dance or club music, not entirely alternative or bedroom rock, and not entirely electronic or house, Porches has carved out a genre of its own. Its music is sensual, playful, sad, imbued with hope, and occasionally contradictory. At their best, Porches’ albums are vast forests or lakes in which you might get lost, submerged, or enclosed, all so that you may eventually open yourself up. The House has this quality, and it is enlivening despite its duller moments.

Matt Wallock can be reached at mwallock@wesleyan.edu.