Chelsea Manning’s visit to campus at the end of last semester had much of the Wesleyan community asking exactly what the Green Fund, which co-sponsored the talk, does at the University.

The answer, naturally, is a bit complex. Julia Michaels ’12 and Julia Jonas-Day ’12 spearheaded initial efforts to create the fund in the 2009-2010 school year, which was approved by the WSA (with support from Josh Levine ’12), the student body, and the Board of Trustees. In an initial plea to the student body, published in The Argus, Michaels, Jonas-Day, and Levine advocated for the creation of the Green Fund.

“Initiatives sponsored by the Green Fund will decrease our carbon footprint and waste, increase our use of renewable energy and increase visibility of environmentally responsible practices on campus,” the three wrote.

Although the fund has certainly not renounced its mission to promote directly sustainable actions, Green Fund projects in recent years have trended toward events that promote awareness and discussion of campus environmentalism over more material initiatives. Manning, whose personal experience with issues regarding surveillance, the military-industrial complex, LGBTQ rights, is not uniquely qualified to address environmental issues. Some, including University President Michael Roth ’78, are curious as to the direction that Green Fund has taken in recent years.

Roth discussed his doubts on how effective Green Fund efforts have been while adding that it somewhat falls out of his jurisdiction, given the student-directed nature of the fund. Roth noted that he is curious about the fund’s dedication to its mission.

“It’s really a student-run budget item,” Roth said in an interview with The Argus. “But I am interested in how, in fact, that money has been used and if it’s actually being used purposefully… From the administrative perspective, I am concerned to make sure that the money that’s collected for the purpose is actually used for that purpose.”

For critics, the decision to fund Manning was questionable given the original mission statement that Michaels, Jonas-Day, and Levine originally elucidated.

Ingrid Eck ’19, who led the Green Fund as the Facilitator in the Fall 2017 semester, maintains that flexibility in what the student board funds is an asset. Environmental justice is a rapidly evolving field, and for the University to have its most beneficial impact, it must remain adaptable and inclusive.

“[We’re] making sure that people understand that they shouldn’t be discouraged from applying if they don’t have a super traditional understanding of the environment,” said Eck. “It doesn’t have to be walking into the forest, or planting some trees—which are wonderful things that we definitely support—but if someone wants to bring a speaker to campus that talks about environmental justice or even intersections of environment and health, or environment and animal rights, or environment and therapy, we’re completely on board with that.”

Jen Kleindienst, the University’s first and current Sustainability Director who also serves as an advisor to the Green Fund, reiterated that the Green Fund makes its decisions on projects to support based on the applications received. In recent months, more applications have been for educational events and fewer for projects that support direct sustainability efforts. Approximately 71 percent of the Green Fund’s semesterly budget was spent on education and awareness-based initiatives last semester, with 27 percent on direct sustainability-focused efforts, and another 2 percent on projects that fall somewhere in between, with a few projects whose final costs have not yet been submitted. She also emphasized that the Green Fund, to which about 90 percent of University students contribute at $15 per semester in the form of an opt-out fee, reviews community proposals rather than formulating its own projects.

“It’s more about who applies and what they are asking for,” Kleindienst said. “I don’t think the Green Fund necessarily prefers a more tangible project, like buying a thing that people will use…rather than having a one-time event. I think it’s more about trying to make sure that whoever’s applying can discuss: What is the legacy of that project? So if you’re going to have a speaker come for a one-time event, can you do a discussion afterward that encourages ‘what will you do?’”

Kleindienst’s final question pinpoints the concerns of skeptics, but Jonas-Day notes that the versatile nature of the Green Fund was founded to reflect the desires of the student body.

“Our driving impetus was sustainability infrastructure,” said Jonas-Day. “But we also wanted to develop something that would give students the agency to make those kinds of decisions about what’s needed on campus.”

Levine remembers his role in the creation of the fund a bit differently, though it should be noted that he served in the capacity of a WSA supporter rather than as an original Green Fund member. He added that his perspective on productive forms on sustainability activism have changed over time, and he now believes that education is more fruitful in the long run than direct environmental actions.

“I was really frustrated with the idea that awareness brings any difference,” Levine said. “I was going through a phase where I was trying to use less water and trying to make my footprint smaller, and I had a moment of reckoning where I felt like, ‘Okay, this stuff really doesn’t matter.’ If we’re gonna make any changes on the scale that I was thinking about, it has to be systemic, it has to be political, or it has to be something in technological innovation. So the idea that awareness on its own is useful, or even that awareness actually turns into any kind of activism or action, it felt like a stretch for me, it didn’t line up at the time.”

If Jonas-Day’s premise is accepted, the crux of the issue becomes whether an event like Manning’s talk can serve as that type of device for “agency.” Some attendees were confused by the topics covered in Manning’s talk, knowing that her expertise primarily lies in whistle-blowing, the prison industrial complex, and LGBTQ rights. But Eck argued that Manning’s fame is exactly why she was well-suited to draw attention to environmental issues.

“Chelsea’s such a notable speaker generally, and we knew that the amount of people she would be speaking to would be so enormous,” said Eck. “We knew it would have a really great impact if even 25 percent of her talk was on environmental issues, we still felt like this was something that we wanted to support because so many people would be there listening to her.”

It’s difficult to ascertain whether Manning’s words were taken to heart by an audience that was surprised by her environmental focus. But at the very least, if the Green Fund was attempting to spark a campus dialogue about the environment, they can consider the event a success.

“We were not expecting to get all the pushback that it felt like we got,” said current Green Fund Facilitator Ori Tannenbaum ’20. “But I guess that’s inherent in having someone controversial come to campus.”

The clearest takeaway from current Green Fund student-leaders is that they are happy with shifting away from more traditional, material initiatives if it means that they can change the way people think about the environment more broadly. While they obviously still encourage student proposals for larger, sustainability-based projects, the Green Fund believes deeply in a more intersectional approach.

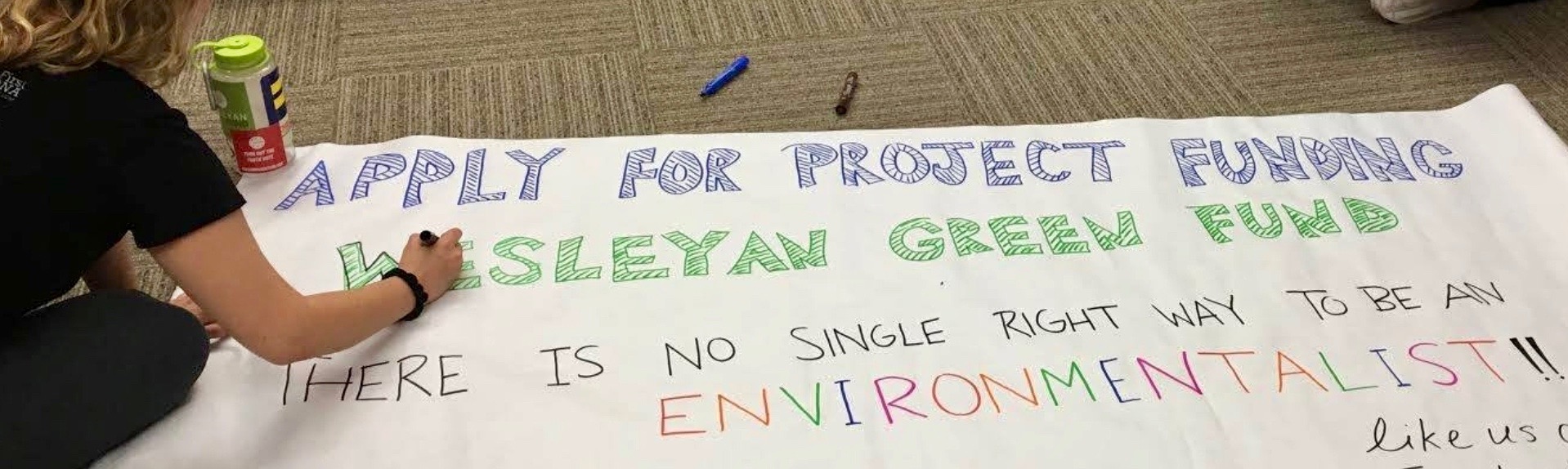

Eck reiterated the group’s new motto: “There is no single right way to be an environmentalist.”

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu.

Sam Prescott can be reached at sprescott01@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply