c/o Thao Phan, Staff Photographer

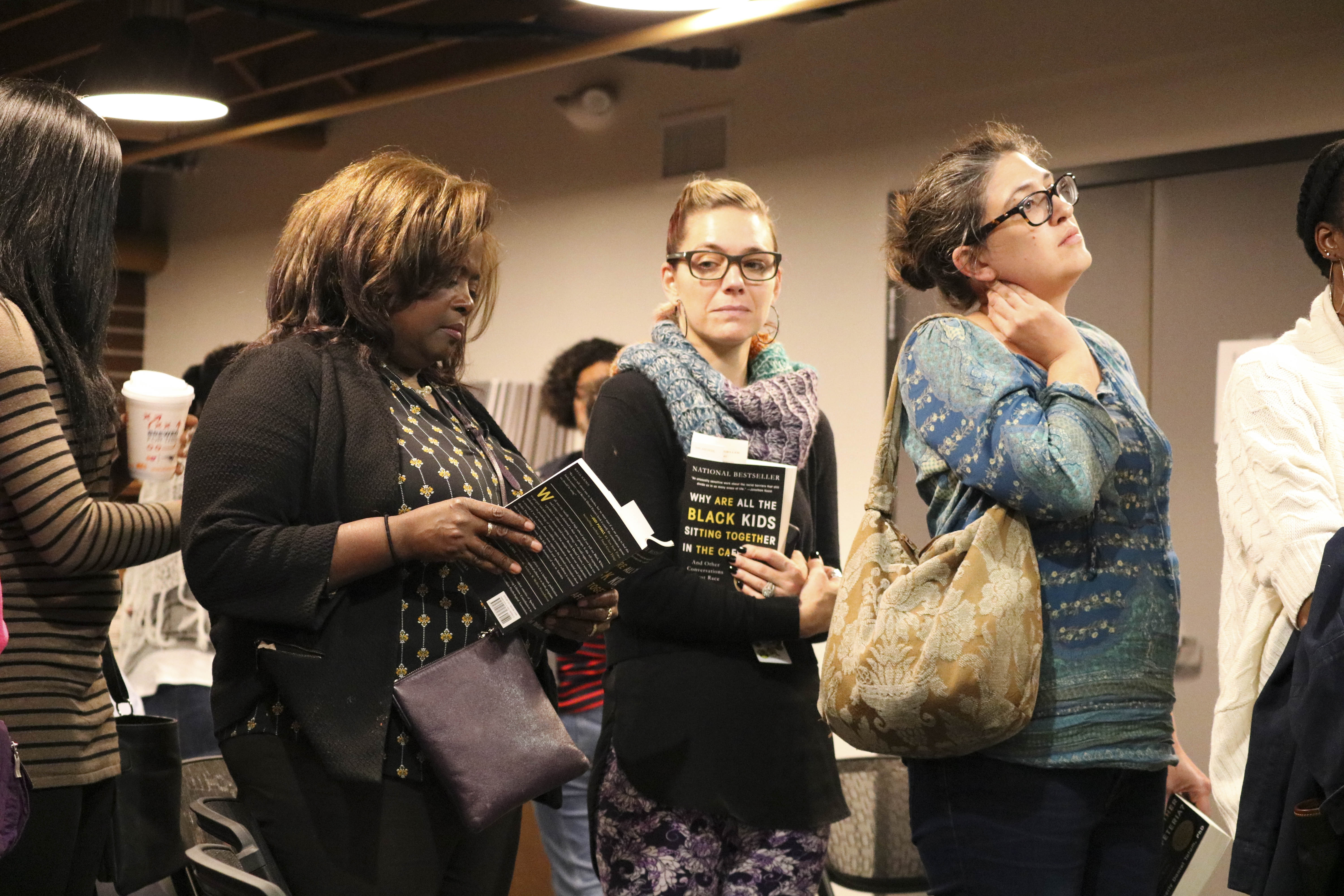

On Friday, November 3rd at 7:00 p.m., the R.J. Julia bookstore hosted a WESeminar with renowned scholar on the psychology of racism Beverly Daniel Tatum ’75, HON ’15, Spelman College president emerita, and author of the seminal work, “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race.” Roxanne Coady, the bookstore’s owner, hosted the live interview.

Tatum, a former member of the Wesleyan Board of Trustees, has held professorships at U.C. Santa Barbara, Westfield State (in Massachusetts), and Mount Holyoke College. Her most cited works are the aforementioned book as well as her 1992 article “Talking about Race, Learning about Racism: The Application of Racial Identity Development Theory in the Classroom.” In 2014, she received the Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contribution to Psychology from the American Psychological Association. It is the Association’s highest honor.

Tatum’s classic work explores racial, ethnic, and cultural identity development in the context of America’s history of systemic inequalities. Since stepping down from the position of Spelman College president, her first project has been to update “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race.”

Tatum began the WESeminar by explaining her rationale for updating the book. She prompted the audience to recall the major national developments which have taken place since the book’s original 1997 release. A 20-year old born in 1997, she said, would have been 4 during the Sept. 11 attacks, 11 in 2008 at the Great Recession’s onset, and 12 in 2009, the year of President Barack Obama’s inauguration.

Tatum said that that same 20-year-old would have also grown up in a new era of civil unrest, an unrest which was most obviously unearthed in 2012 with the shooting of Trayvon Martin, and further exacerbated with the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown. Other fatal shootings of unarmed black citizens, the rise of Black Lives Matter, a 2016 election characterized by relentless racial animus, and this past summer’s “Unite the Right” rally, Tatum explained, have all produced a profoundly alerted cultural landscape, remarkably different from the one that existed when she initially wrote the book.

c/o Thao Phan, Staff Photographer

Throughout her conversation with owner Coady, Tatum would illustrate examples of systemic racial exclusion which underrepresented Americans have faced, especially Black Americans. She explained that the Chicago Board of Realtors once threatened its agents with license revocation if they gave tours of houses to Black clients; that the suburban homes white Americans purchased with GI Bill funding were tainted with covenants forbidding future sale to Black and Jewish Americans; and that cities across the U.S. have systematically denied communities of color access to capital and thus property through the process known as redlining.

“Those neighborhoods were redlined—literally a red line drawn around them—and therefore ineligible for funding,” she explained. “The FHA [Federal Housing Administration] had a system of categorizing neighborhoods as green, blue, yellow or red. Green was new construction, all white; blue was older but still white; yellow was neighborhoods in transition; red was neighborhoods occupied, primarily by people of color, most specifically African American. So if you were forced into a redlined neighborhood because of the other [discriminatory] policies and practices, you couldn’t get loans to buy property or fixed properties in those neighborhoods. All of that contributes to the real estate housing patterns we see today.”

The conversation turned efforts to school integration which followed Brown v. Board. Tatum explained that in the 1990s she consulted superintendents of towns participating in Greater Boston’s METCO program, the Commonwealth’s voluntary school integration program. METCO’s goal was to eliminate the achievement gap between minority students from Boston and their white suburban counterparts. Tatum would establish affinity groups in her work, in which groups of integrated students participated in informal discussions. These adult-facilitated groups were found to increase minority student performance and encourage cooperative behavior from the suburban white students (as opposed to bullying or boycotting).

Audience questioning prompted Tatum to differentiate active racism from passive racism, and to emphasize the role systemic—not just interpersonal—racism plays in perpetuating societal inequalities. It is only through concerted attempts to disrupt broader racial disparities that an individual may affect meaningful change, she explained.

“Doing nothing simply reinforces the status quo,” she said. “You might not be intending to do that, but it is so self-perpetuating that unless you are actively moving in the other direction…you’re going to get carried along [by the impacts of systemic racism]. So I always think the most relevant question is never, ‘Is so-and-so a racist or not;’ I think the most relevant question is, ‘Is that person actively working against racism?’”

c/o Thao Phan, Staff Photographer

Tatum transitioned from teaching and research positions in higher education to administrative capacities. In 2002, she became the ninth president of Spelman College, the nation’s oldest historically-black women’s college.

Tatum spoke of scenes of inspiration from her time at Spelman and strategies that parents and educators can use to overcome passive racism. She discussed examples of other racial disparities throughout the talk, like that American schools are more segregated than they were in the 1960s, or that in 1950 the U.S. population was 90 percent white.

Tatum mentioned that even though 90 percent of surveyed 20 year-olds admit to having witnessed interpersonal bias (like interpersonal racism, only a fifth of them express that they feel comfortable talking about such incidents). She attributes this reluctance to a process of early socialization that discourages mention of race.

“I’d describe them as not color-blind, but color-silent,” she said. “When we talk about racial, cultural, or ethnic identity, we’re talking about that identity that comes from living in a race-conscious society. And it’s shaped by the feedback we get from early in our lives, throughout our lives, in terms of how people are responding to our racial group membership.”

To illustrate her point, Tatum prompted audience members to recall the first instance of racial bias they ever witnessed. Largely, these incidents occurred at a young age and were not accompanied by a conversation with adults to make sense of them.

“One thing you will probably know about those 4, 5, 6, and 7 year-olds is that they’re pretty candid, that they don’t filter much,” she said. “And yet we just saw that a large group of people had early experiences, race-related, which made them feel uncomfortable, [but that] most of those people did not talk about it at the time it occurred, even though we know that 4, 5, and 6 year-olds are pretty chatty.”

She expanded upon the idea that people are socialized not to talk about race.

c/o Thao Phan, Staff Photographer

“The process of learning not to talk about it has deep roots in our personal histories,” Tatum said. “It goes back a long way. So many people get knots in their stomach when they are prompted to talk about race…a lot of teachers, and parents too, when they’re with children who are asking questions, or bringing issues up, or wanting to talk about [race] and they don’t know how to respond, they don’t have practice, they may often respond in a way that really cues, ‘This is not a conversation I want to have.’ So not having the conversation, you can’t solve a problem without talking about it.”

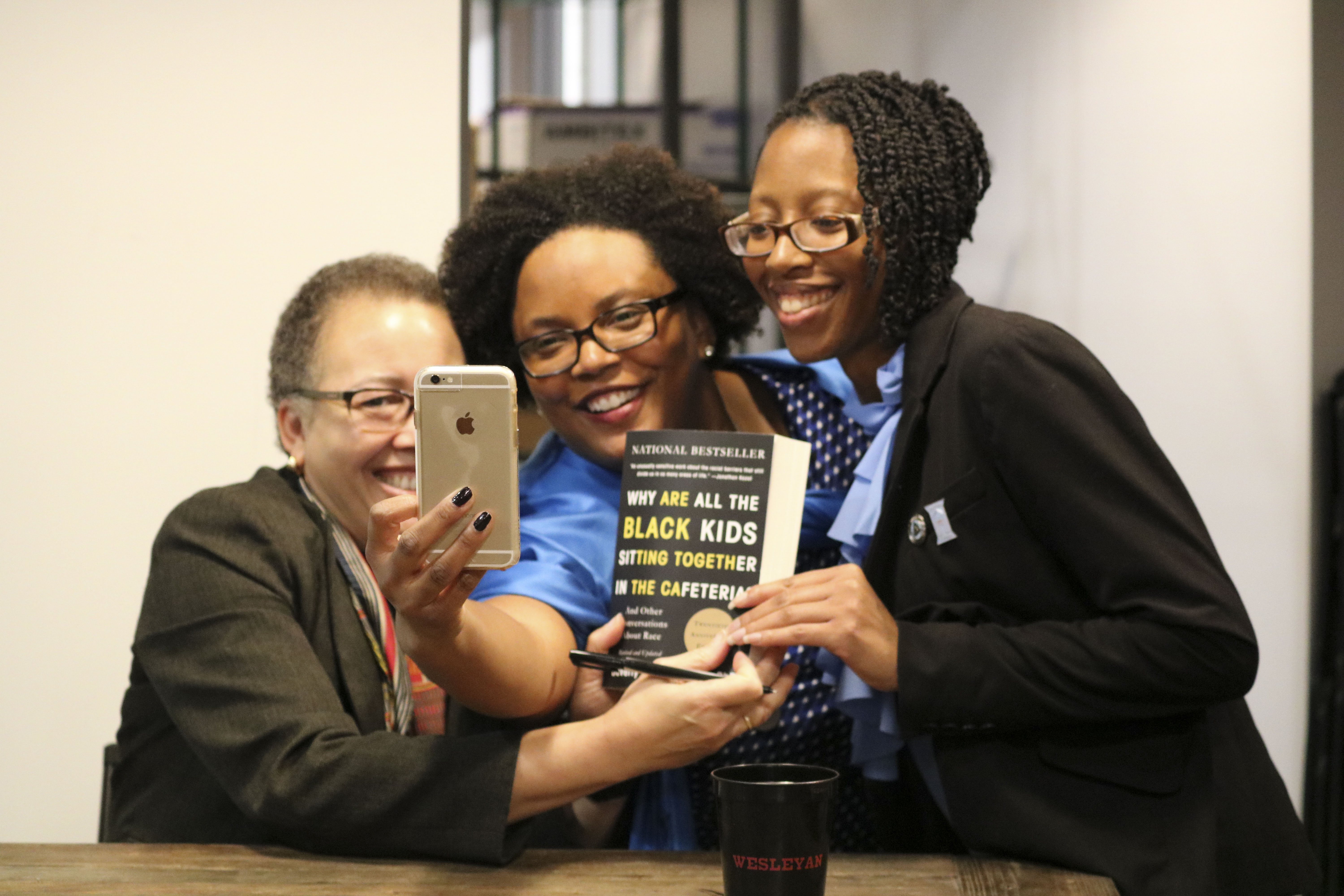

Coady concluded the event by urging audience members to begin and sustain honest conversations about race and difference. She praised book clubs and audience members purchasing copies of her book. A signing followed the event.

Brandon Sides can be reached at bsides@wesleyan.edu.