c/o filmlinc.org

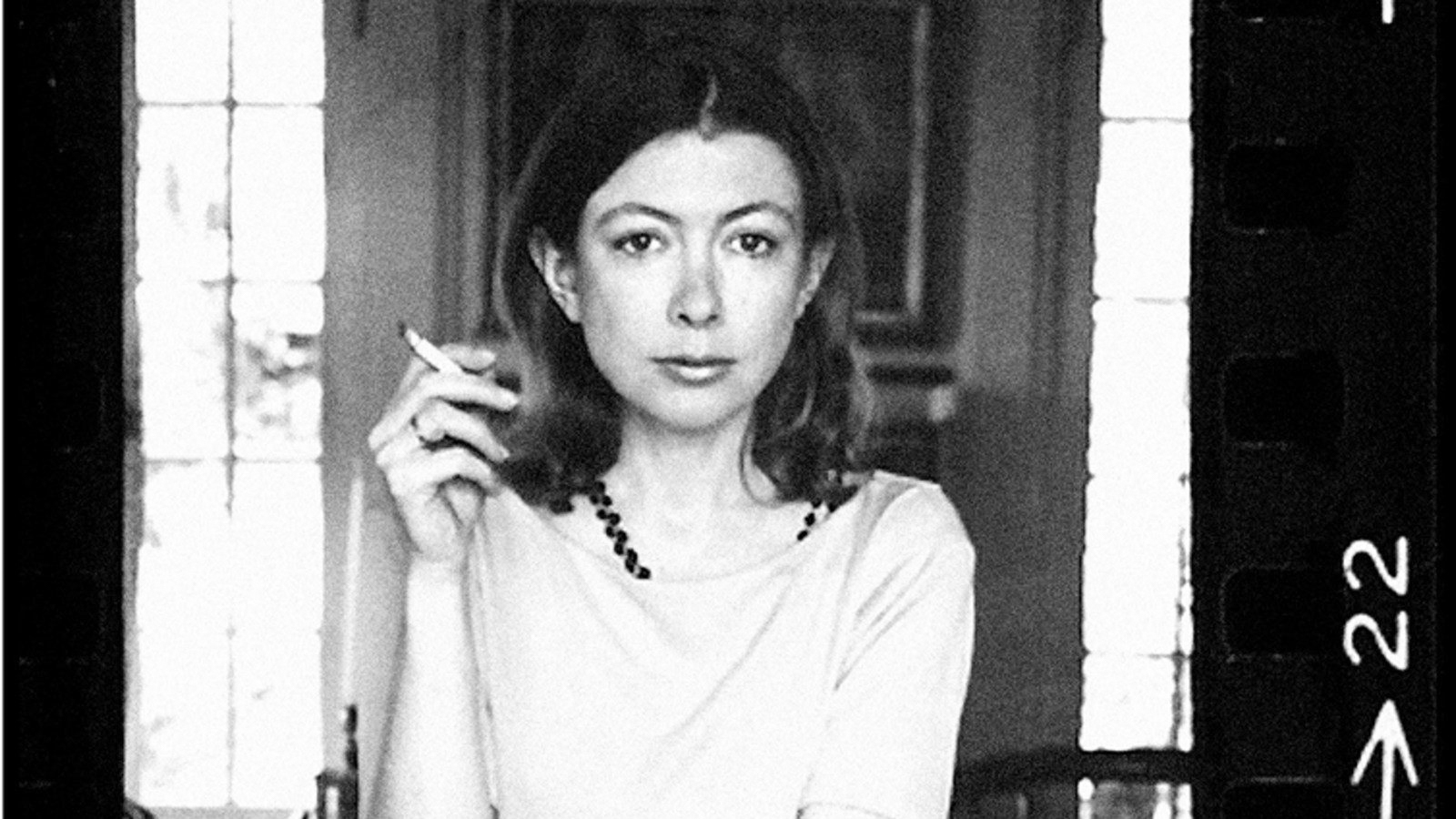

Griffin Dunne’s recent biopic of his aunt, “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold (2017)” was released on Netflix on Oct. 27. An affectionate portrait of Didion that both benefits and suffers from Dunne’s tenderness toward his subject, the film comprises dozens of interviews with Didion’s friends, family members, and current and former colleagues, all of whom seem eager to contribute their praise and memories of Didion to this project. The film also includes family photos, home videos, newspaper and magazine articles, media clips, readings of Didion’s work, and interviews with Didion in her apartment, which lend it a casual, unexpected intimacy given Didion’s (paradoxical) penchant for privacy.

Dunne structures the film around Didion’s career, charting her life through her published works. He provides some biographical information when necessary, but his narrative voice is gentle and unobtrusive. Instead, he turns to Didion and her familial and literary cohorts to tell her story.

We start with “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” then we make our way through nearly all of Didion’s essay collections, novels, and screenplays. We move through “Run River,” “The White Album,” “Play It As It Lays,” “The Panic at Needle Park,” “Political Fictions,” and “Where I Was From.” We follow Didion, via her writing, from Sacramento to Berkeley to New York to Los Angeles to El Salvador, and back to New York. Much of the film lingers on “The Year of Magical Thinking” and “Blue Nights,” which chronicle the deaths of Didion’s husband (writer John Gregory Dunne) and daughter, respectively.

Dunne’s chronological tracing of Didion’s life is interspersed with the writer’s personal reflections and her loved ones’ memories of her. Interview subjects range from Vogue editor Anna Wintour to the actor Harrison Ford (whom Didion and her husband apparently employed as a construction worker long before he was an actor) to the writers Calvin Trillin and Susanna Moore to Didion’s brother Jim. In most interview segments, we see subjects reaching far into the past to recall little episodes or incidents of the Didion-esque: deeply ingrained images and vignettes that speak to her characteristic combination of detachment, glamour, and independence. These interviews exude nostalgia, love, admiration, and fandom. They rarely reveal anything about Didion that her readers wouldn’t already know.

The standout interviews are those with writer and critic Hilton Als, former New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers (who died shortly before the film was finished), playwright David Hare, and Didion’s literary agent Lynn Nesbit. Als, Silvers, Hare, and Nesbit each bring critical sensibilities to Didion’s work, succinctly contextualizing and interpreting her cultural and literary significance alongside their own personal memories of her as a friend and colleague.

Hare brilliantly notes that the “horror of disorder…is very much a feature of Joan’s writing, and her personality,” a comment that resists the dominant sweetness of this film by shining some light on the darker parts of Didion’s psyche. Als adds, “The weirdness of America somehow got into [Didion’s] bones and came out on the other side of a typewriter.” Silvers explains how Didion consistently used her outsider status as a literary strategy. Nesbit, in discussing Didion’s writing practice, offers this simple but important point: “With Joan, I think she always writes to figure out what she thinks and what she feels.” Later, Didion confirms this: “It unfolds as you write it.”

Vanessa Redgrave, in a quietly revealing moment, describes Didion as “dark glasses glamorous,” which highlights the central paradox of Joan Didion: her dual tendencies to report and withhold. Her essays and memoirs are imbued with personal information and details, yet her cool prose style gives off an undeniable sense of emotional detachment. Even when she divulges a great deal of personal information, she assumes a posture of restraint. This tension between accessibility and remoteness in her writing is alluring to some and frustrating to others. Didion’s notorious sunglasses perform this tension, serving as a visual and physical signifier of the separation and distance evoked in her prose. Didion, as the theory goes, prefers seeing over being seen.

Dunne doesn’t try to get behind Didion’s glasses. He is content accepting her self-presentation as herself, her style as her. At one point, he sheepishly raises a concern about her weight. (Didion, we learn, had once weighed 75 pounds as an adult.) Despite her small frame, this weight is alarming, and it is fleetingly suggested that she has struggled with weight before. Dunne doesn’t probe. He drops this narrative thread quickly and cleanly, turning to a confusingly upbeat anecdote about Hare forcing Didion to eat meals on a regular interval while working on a play together. This seems to be Dunne’s approach to negativity: Only the negativity that Joan has already sanctioned in her published work is on the table. Such an approach fits neatly into the film’s underlying logic that Didion is her self-styled persona.

Dunne, in attempting to profile a literary figure, ultimately profiles a literary career—or at least conflates the two. Although it is a genuine pleasure to hear Didion’s texts read aloud, these texts dominate a film that could have ventured further into the extra-textual, or the areas of Didion’s life that she herself has traditionally deemed off limits. Dunne’s decision to include footage of Barack Obama giving Didion a National Medal of Arts and Humanities in 2013 underscores his desire to celebrate, recognize, and honor his aunt. This desire animates the film, which explains why it has the affective texture of a living memorial. It is a collaborative tribute to a literary icon whose oeuvre can too easily be interpreted as installments or chapters of an autobiography. In other words, the story that Griffin tells about Didion is not all that different than the one that Didion has told about herself.

At the end of “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” there is a slide worth revisiting. It’s titled, “READINGS FROM THE WORK OF JOAN DIDION,” and it lists, in order, every text from which Didion read in the film. The list’s typography evokes that of a typewriter, and it is marked with underlines, stars, circles, and arrows that, at first glance, appear handwritten. It’s a tacky addition but one that is useful for thinking about the film as a whole. While the slide succeeds in highlighting some of Didion’s finest works, it points to the film’s over-reliance on them.

Dunne proves to be a less compelling storyteller than Didion, but surely we can’t fault him for this—it’s an unfair comparison. And despite the film’s title and shortcomings, its center does hold.

Matt Wallock can be reached at mwallock@wesleyan.edu.