Last year, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick was virtually banished from the NFL after his peaceful national anthem protest. Steve Wyche, an NFL reporter, asked Kaepernick for the reason behind his protest. He explained that he would not pledge his allegiance to a country that has oppressed people of color and tolerates police violence against African Americans. While Kaepernick was responding to police brutality and mass incarceration, his protest also raised questions about the intentions of the 19th-century composer of the United States’ national anthem, Francis Scott Key.

In the conclusion of his book “Scraping By,” Dr. Seth Rockman explains how Key envisioned the new republic as a haven for white men, women, and children with the absence of people of color. Dr. Rockman was involved with the American Colonization Society (ACS), which argued for the emigration of free people of color to the ACS-established U.S. colony of Liberia. The society believed that free African Americans would have a better life in their ancestral homeland due to the inhospitable, racist character of America. Other members of the ACS included Senator Henry Clay (who founded the Society in 1817), former Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, and future president Andrew Jackson. One lesser-known individual in the society was a prominent figure at Wesleyan: Wilbur Fisk.

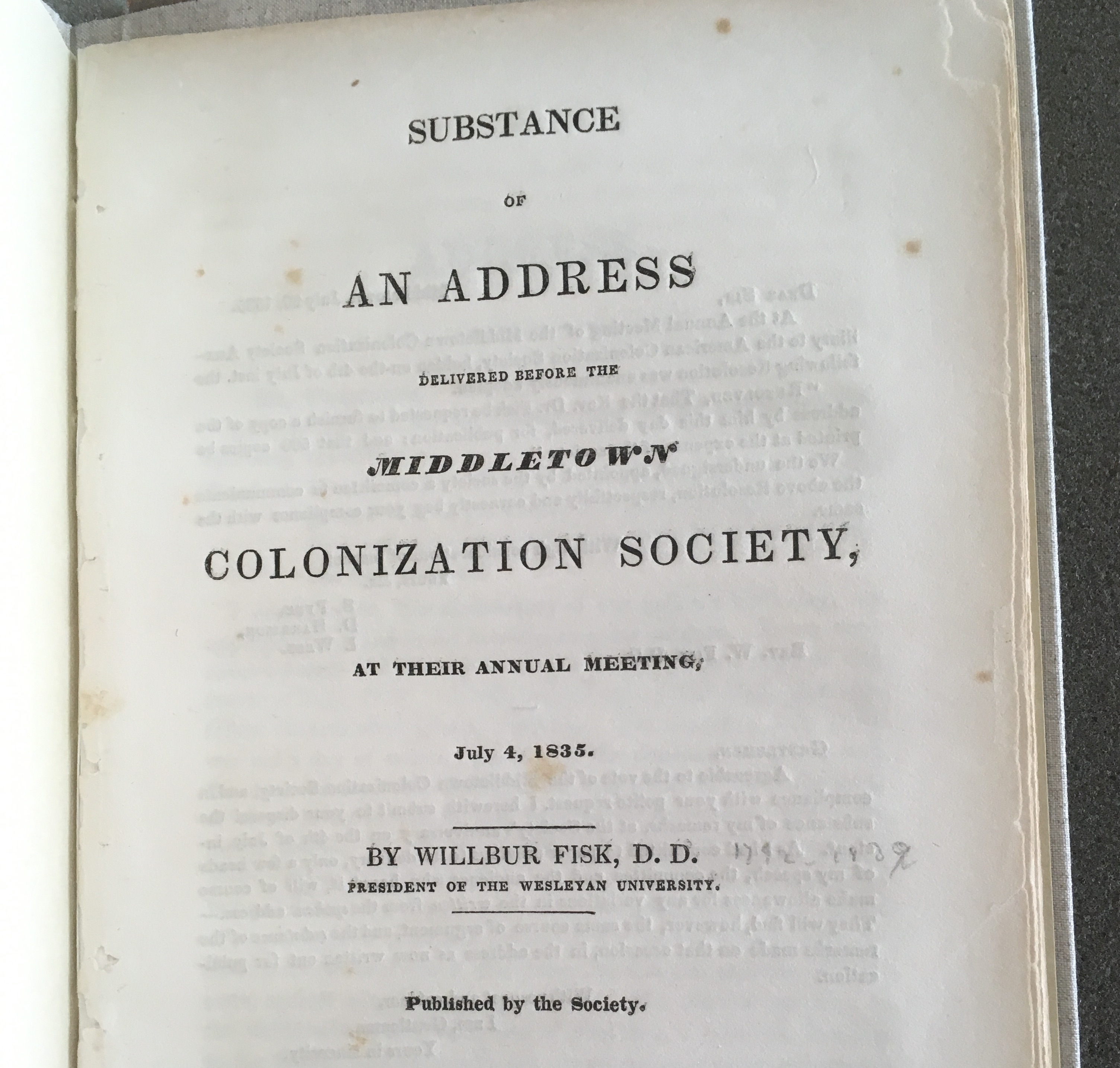

Fisk, the first president of the University—a position he held from 1831 to 1839—was a prominent educator and Methodist theologian as well as a member of the ACS. On July 4, 1835, he delivered a speech to the Middletown chapter of the society defending the organization’s purpose and motives. A transcription of the speech, entitled “Substance of An Address Delivered Before The Middletown Colonization Society,” can be found in the Special Collections & Archives in Olin Library.

Blake Maybeck ’05 previously examined the larger scope of the president’s views in his thesis, “The Colonization Controversy of the 1830’s through the Eyes of Wilbur Fisk,” which is also housed in Olin’s Special Collections & Archives.

The speech began with Fisk’s interpretation of Independence Day.

“The 4th of July is our political sabbath consecrated to the intellectual services of Freedom’s altar,” he said. “A day of deep thought, of close investigation, of firm intellectual discussion and lofty moral action.”

Moral action for Fisk and the other white men attending the meeting consisted of strengthening the society’s policies, which they believed benefited Black people. He explained how taxation could fortify the foundations of the ACS, which built schools and churches in Liberia to educate the African man. There is no mention in the document of the society’s intentions to help Black women.

To demonstrate the importance of the ACS, Fisk boasted how it had liberated a substantial number of the enslaved peoples in America compared with the Anti-Slavery Society, which he claimed had not liberated a single individual. Nevertheless, he did admit that a number of ACS members were slave owners. It is certainly plausible, then, that many of the enslaved people sent to Liberia by the ACS had been owned by its members.

Fisk organized his criticism of the Anti-Slavery Society around issues of consent and their desire for the immediate eradication of slavery. He argued that the enslaved did not consent to freedom because the Anti-Slavery Society did not ask them if they wanted to be liberated.

While the ACS approached abolition cautiously, the Anti-Slavery Society desired immediate change. Fisk expressed this distinction.

“We [of The American Colonization Society] hope by gradual amelioration, to elevate the oppressed [man of color] to his rightful standing in the great human brotherhood, without hazard and without civil convulsion,” he said. “While they [The Anti-Slavery Society], on the other hand, consider such gradual alleviation of the condition of slavery, as tending directly to perpetuate the evil.”

The debate about the gradual approach versus immediate abolition continued until 1863 when President Lincoln, an early supporter of the ACS, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that freed the enslaved in the Confederate States. Fisk predicted southern secession over the issue of slavery, which would only be resolved by war.

While the ACS and the Anti-Slavery Society were divided over the process of emancipation, according to Fisk, a Methodist minister, the unifying principle between the two societies lay in religion.

“We are united almost by a common pastoral charge, by which the flock is the property of each and every pastor, and each and every pastor is the property of the whole flock,” he said.

Fisk’s speech can also be read as a commentary on racial prejudice in the United States that still defines society today.

“The greatest and almost the only disabilities of the free [people of color], in this country are resolvable into what has been called the prejudice of color,” he argued.“In combatting this prejudice, the first inquiry should be is it ‘vincible’ or ‘invincible?’ Does it exist in nature, or is it the effect merely of education and causal association?…Our instincts, physical and moral, act independently of reasoning; and they dictate that anything like a social or domestic equality between the two races [can] never be enjoyed.”

He also speculated that equality between white and Black people could be achieved and provided one suggestion for how the abolitionists might create this equality.

“The strong and instinctive lies of sex and consanguinity, were evidently designed by the God of nature, to be the elements of society. Remove these therefore, and political and social equality is visionary,” he argued. “[They can promote] the conjugal union, and the domestic amalgamation of the two [races], or they must give up the inconsistent and chimerical idea of a social and political equality.”

At the conclusion of his speech, he praised the work of the ACS.

“We [the American Colonization Society] need more interest, more zeal, more liberality in this work,” he said. “It is increasing the faculties and comforts of the colony, it is rectifying former mistakes, enlarging and improving its plans, paying off its debt, at the same time it is defending itself against slander and opposition at home and abroad. The contributions of this day, and our labors and munificence in this cause, hereafter, will show, I trust, that we are faithful and efficient friends of that noble enterprise, which is laying a foundation for the future independence of the degraded, oppressed, and exiled sons of ‘abused and bleeding Africa.’”

Some two centuries later, the University has yet to make reparations for Fisk’s involvement in the ACS. Several students on campus have discussed renaming Fisk Hall as a possible way to address this issue. The questions must be raised: should his writing be studied and discussed in the classroom? Should there be a history class on the founders of the University at some point in the future? One thing seems clear—Fisk’s history with race, colonization, and slavery deserves to be a part of the University’s consciousness.

Tristan Genetta can be reached at tgenetta@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply