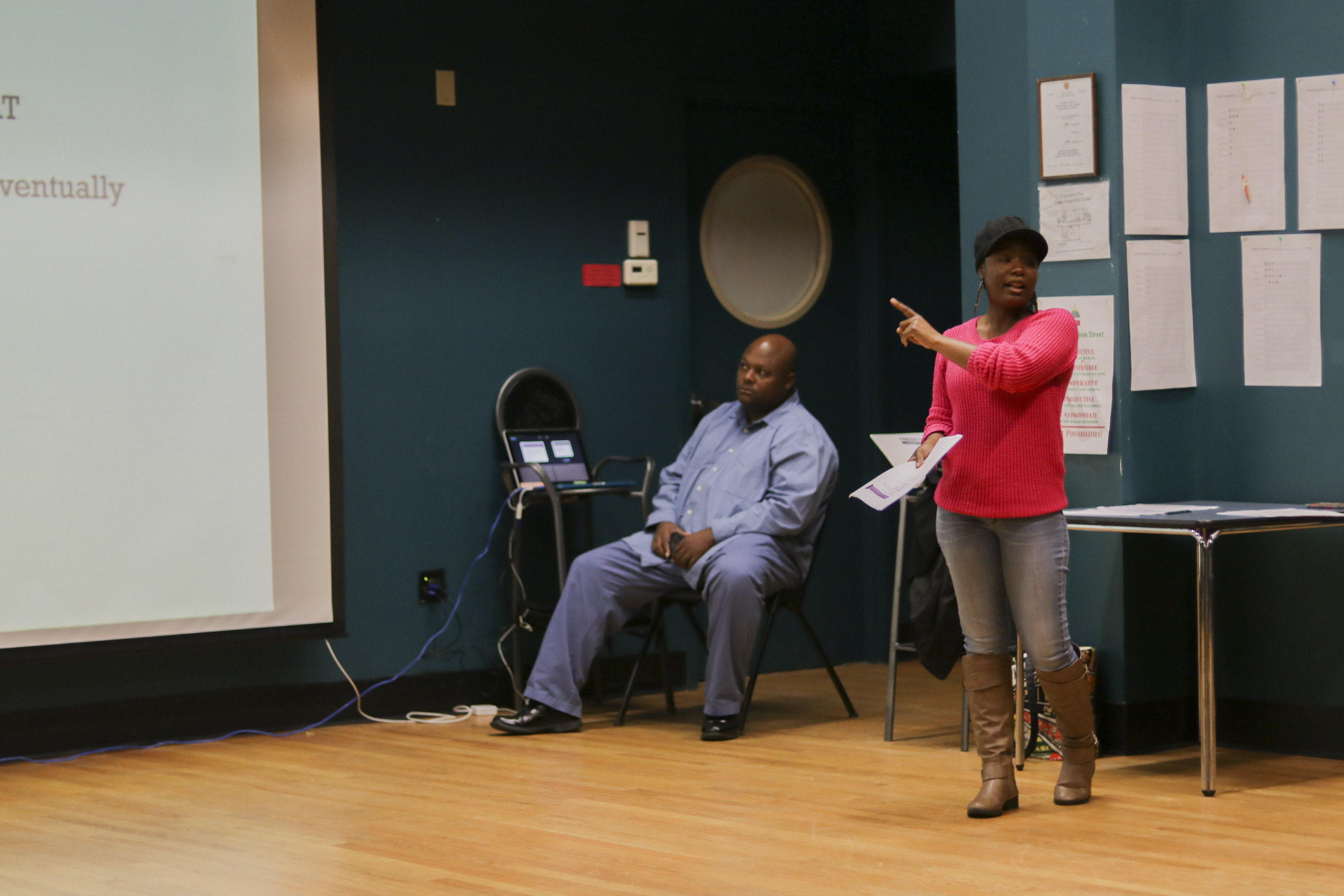

“We are here tonight to focus on the Green Street Teaching and Learning Center,” said North End Action Team (NEAT) Community Organizer Precious Price. “This is a working task force. We do not sit around and try to play guessing games with each other. We’re really trying to get something done.”

Price was speaking at the start of the second NEAT Community Conversation about Green Street on Nov. 1, the first NEAT meeting open to the public since the task force’s creation. Comprised of urban rights activists, members of the University community, and current Green Street staff, the task force started in response to the impending closure of the Green Street Teaching and Learning Center, a crucial pillar of Middletown’s North End neighborhood. It currently serves up to 3,000 residents a year.

The City of Middletown, the University, and NEAT were the three initial partners in the creation of Green Street. Since its beginning in 2005, the center has served as a multipurpose educational organization, offering a wide array of programs, such as after-school classes, private lessons, artist residencies, homeschool programs, a Girls in Science camp, a math institute for teachers, and a science safety workshop for teachers, among others. In recent years, its focus has shifted from solely arts to incorporate a science-based learning model.

Green Street has worked with students representative of all eight public elementary schools in Middletown. On average, 70 kids take classes there each semester. A third of these students live in the North End, and 60 to 70 percent are people of color.

In terms of enrollment and financial aid, Green Street has worked to make classes affordable for lower-income families. The advertised price for a class is automatically reduced by 80 percent for families whose kids receive a free lunch through their school, and the center has provided full scholarships for families in need. Approximately 75 percent of students receive some form of financial aid for tuition.

When University President Michael Roth ’78 announced the center would be shuttering its doors next summer—citing the financial strain on the University—Middletown community members, and center staff, and many from the University were stunned. After speaking to several Wesleyan faculty members and center staff members, however, a slow but steady decrease in funding became evident over the past decade.

“The three-way funding, all of that dwindled at one time,” Price said. “They had to cut programs, they had to cut kids, and eventually we got here.”

“The type of collaborations we ought to be having”

Director of the Allbritton Center Robert Rosenthal played a role in the center’s founding back in 2005.

“Importantly, it was the community’s idea, not Wesleyan’s idea,” he recalled. “I think it’s a model of the type of collaborations we ought to be having.”

Rosenthal also noted that the University’s intentions were not solely to improve the North End for the benefit of its residents.

“A lot of that was out of self-interest of Wesleyan,” he said. “It wasn’t in Wesleyan’s interest for the North End to get worse and worse and prospective students to be scared by it…. We’d hoped that it would be so impressive as an arts center that it would draw in middle-class families.”

Director of Planning, Conservation, and Development for the City of Middletown Joseph Samolis also spoke of the center’s early days in an interview with The Argus. As former chief of staff of Mayor Dan Drew’s office, he worked closely with Green Street over the years. After the city acquired the building located at 51 Green Street, the city government began its work to refurbish the interior of the building.

“The general idea was to create an environment for the people on the North End to have a resource center of some sort within their neighborhood,” Samolis said. “The city helped secure grant funding for the rehabilitation of the building so that it could be opened up as a Green Street Arts Center. From that point forward, when Wesleyan was involved, the city still maintained the capital needs of the building, like a roof replacement. The city absorbed that cost.”

“It’s [the city’s] building,” Director of Green Street Sara MacSorley explained to The Argus. “We [rent] it for a dollar a year.”

The center’s annual budget amounts to $500,000, with a significant portion coming from grants, donations, and tuition. In its early years, the three contributing partners—Wesleyan, the city of Middletown, and NEAT—had hoped the center would eventually gain 501(c)3 status. That would mean it could sustain itself without direct contributions from the University, which have amounted to approximately $4 million dollars over the course of the center’s 12-year existence.

“We had cut Wesleyan’s contribution more than 50 percent from its high point, but a lot of that was based on being very successful at getting state grants,” Rosenthal said.

When the Great Recession hit in 2008, Rosenthal, who served as academic provost from 2010 to 2013, stressed its financial implications as a turning point in the University’s involvement.

“People on the board of trustees, and the president, and others, were worried about how much money we were spending on Green Street,” Rosenthal recounted. “Green Street, when it was first formed, was in the days when we thought we could spend as much money as we wanted on anything, so after the [2008 stock market] crash, people were a lot more worried about money going out. So, at some point, Michael Roth and I agreed that we would move Green Street under Cathy Lechowicz at the Center for Community Partnerships and that we had certain targets that President Roth wanted us to meet in terms of cutting costs and upping use, and those were targets that we met.”

As a student coordinator for Green Street, Katie Murray ’19 had several conversations with University administrators who were involved in the University’s decision.

“[Current Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs] Joyce Jacobsen kept repeating, in the meetings we’ve had with her, that in that competition for grants, Wesleyan ended up taking grants from other after-school programs that could’ve gotten them in Middletown,” Murray said. “And she found that to be a weird scenario where we, this privileged institution, were taking things from other non-profits who are just trying to survive in the town.”

“Calculated” and “Abrupt”

Samolis stressed the city’s support for Green Street. The University made the decision to defund the center on its own.

“I think a lot of people think that the city is somewhat responsible for the closure of Green Street, and that is not the case,” Samolis said. “The city isn’t involved in the day-to-day administration of the center. It is there for supporting the actual structure. It is a city building, and we take on the responsibility of all the capital investments in the building.”

At the NEAT Community Conversation, Price emphasized the same point.

“The city has kept up its end of the partnership, which was something I know the community felt really strongly about, that the city didn’t, but they actually have,” she said.

On June 23, 2017, University President Michael Roth announced the closure of the center.

“While Green Street contributes to the community in many important ways, we believe we need a new model for supporting the community engagement of our students,” Roth wrote.

Green Street Student Coordinator George Perez ’20 was quoted in an Argus article earlier this fall, expressing disdain over the administration’s timing.

“What was particularly frustrating was that the decision was made in the summer and that’s obviously a time when the after-school program is not in effect,” Perez said. “I think that decision was calculated to make it really awkward for students who would oppose this decision to do so.”

Perez and Murray expanded on these sentiments in a Letter to the Editor to The Argus.

“This abrupt decision, made over the summer without consulting the numerous Wesleyan work study students who tutor there and the numerous Middletown families who put their faith in the program and, in turn, the University, calls into question exactly what kind of ‘deep connections’ with the community Wesleyan seeks,” the pair wrote. “Green Street provided Middletown families, regardless of their financial standing, with a safe communal space devoted to the cultivation of child creativity and the progression of child learning.”

In the following months, individuals from various involved parties have worked both together and independently to try to confront the impending loss of the institution.

“I don’t think it will ever be the same and that’s why it’s so upsetting,” Murray said. “I think that something is going to happen. We’re a creative student body and we’re going to come up with stuff…. I know a lot of my Green Street staff is upset and charged and ready to make something out of this, and not just sit back, so I find that heartening.”

Philosophical Organization for Women of Color (SOPHIA) Founder and President Gabe Hurlock ’20 first became involved with Green Street this past spring. Hurlock is transforming SOPHIA, once a more discussion-based organization, into a political action group.

“I’m on the school-campus side, where I’m trying to rally the students, because that’s also an issue,” Hurlock said. “The Wesleyan campus is still psychologically separated from the Middletown community, and that’s been proving to be a bit of a disservice, because while we’re being educated on the issues, we’re not connecting and functioning in the community to address those issues, and so that’s where we fall short, as a campus…. You realize that there’s this big capitalist machine or this big sociopolitical issue at hand, that is affecting all of us, but the question is: ‘Where do you start? And where do you actually have power?’”

Apart from the students’ reactions, full-time staff expressed mixed attitudes over job security, the future of Green Street as an institution, and the site of future programs.

“As far as the Wesleyan staff who work here, [the University has] been fantastic with pairing us up with [Human Resources] to make sure that they really understand what everyone’s skill sets are, and interests too, so that as things become available, they can match people where they would be a good fit,” MacSorley said. “That’s happening already. We’ve had our administrative assistant at the front, Ryan Launder, who’s already taken a position up on campus…. They are trying to place the people who have been here in something that makes sense.”

Although the University has been working to transfer full-time staff, employment is only guaranteed up until the summer of 2018.

Concerns about Green Street’s closure expand beyond the empty building. The loss of offerings will have an undetermined but definite effect on day-to-day activity for families whose children attended the programs.

“With it leaving, I think it’s gonna be a disconnect within the neighborhood,” said longtime Green Street teacher Marc Pettersen. “Not a huge thing, but over time I think we’ll see that happen.”

“We’re forgetting about the younger ones”

Many involved with Green Street operations have voiced uneasiness over the loss of programming and the building’s future prospects. Mayor Dan Drew’s office is currently accepting proposals from local businesses and groups.

“The facility is being turned into a soup kitchen,” Hurlock asserted. “I mean, they’ve come in…and so if that’s not a sign that it’s pretty much gonna happen, then I don’t know what is. It hasn’t been written contractually yet and set in stone, but the city is going to do something with the space—rehabilitation center or soup kitchen. Now, the issue with that is that Middletown community members who live on that end of Main Street do not want a soup kitchen in the middle of their neighborhood.”

Rumors have circulated about St. Vincent de Paul already having made an informal deal with the city. De Paul, which is currently located at 617 Main Street, offers four main services: a soup kitchen, a food pantry, support housing, and a community assistance program that provides various forms of help. Samolis pushed back against this claim.

“St. Vincent de Paul is looking for a new space,” Samolis said. “They are evaluating properties in the North End because they would like to stay local to the clientele that they serve most. They went and looked at Green Street in terms of the space. Again, as I mentioned, Green Street was designed for a specific purpose. St. Vincent De Paul needs to determine where or not that building layout would fit their needs and they’re going to have to make a proposal to the city as to its future use.”

A local landlord at the Nov. 1 NEAT Community Organizing meeting spoke out against moving the soup kitchen to Green Street.

“Everyone needs a place to go, but not here,” he said.

While no deal has officially been reached, Samolis expressed a sense of urgency in finding a new tenant to fill the building.

“I think having a vacant dormant building anywhere is not necessarily good for a neighborhood,” Samolis warned. “Ideally, we would like to see potential uses come about within the next few months so the mayor and council can evaluate proposals so that we might be able to get a lease agreement in place before the end of June when Wesleyan is looking to vacate the property.”

At Wednesday night’s Community Conversation, Green Street Afterschool Supervisor Cookie Quiñones expressed fears that the center would lose its support of local youths.

“We’re letting the younger youth—we’re dropping them off,” Quiñones said. “We’re forgetting about the younger ones [who can help] build the community better…. We’re all, all over the place. We’re trying to do everything, but at the end of the day, we got more kids coming up.”

“Going to have to look different”

“The reason why we created this task force is because we had a very disappointing meeting with the mayor, who couldn’t promise us anything,” Price told the attendees at NEAT’s Community Conversation.

“We found out that Wesleyan has a civic engagement plan going on,” Price continued at the meeting. “And we found out that they may decide to put the money that they set aside to still support the community into something else. Before that money dwindles and they give that pot of money away, we want to come up with something.”

While not necessarily addressing community concerns over the empty space, the administration hopes to continue some of its programming. President Michael Roth ’78 spoke to The Argus about Wesleyan’s Civic Action Plan, which has been in development since before the decision to shut down Green Street.

“We will be developing a civic action plan that will use some portion of those funds for programs involving students in Middletown,” Roth said. “We haven’t fixed on what those will be exactly yet.”

MacSorley outlined initial steps.

“Wesleyan is still involved in figuring out what they can do next that engages the community,” MacSorley said. “It’s just going to have to look different. The Director of the Center for Community Partnerships, that is a position that is currently open…so I think once they fill that position, whoever that new director is gonna be, is gonna be really important in figuring out what Wesleyan wants to do in continuing work with the North End in a way that’s not just effective for the college student experience, but also really meaningful for the people here on the North End.”

Although not all decisions have been made yet, Associate Provost Mark Hovey went into detail about which portions of Green Street programming the administration has committed to sustaining so far.

“We plan to continue the K-8 summer math institute, where Wesleyan and other faculty work with K-8 teachers to improve math teaching; Central Connecticut will take the lead on that,” Hovey wrote in an email to The Argus. “We hope to continue the Girls in Science camp on Wesleyan’s campus, but that is grant funded so it will depend on whether we can get the grant again. There is a recording studio at Green Street where [private instructor] John Bergeron teaches classes, and we are looking into ways to move that onto campus.”

Despite these aspirations, many of those involved are concerned about the center’s legacy.

“My worry is that everyone will forget when it’s gone,” Murray said.

“Empowerment is not given to you”

Vera Benkoil ’18 has worked at the Center for three years and has led several classes.

“I just have so many moments where children actually recognize something and seeing them put that to practice,” she reminisced. “When you can dance with a kid or collaborate on an art project with them, that’s just something.”

Benkoil has been conducting a series of interviews with volunteers and employees on what the center has meant to them. She hopes that it will take the form of a presentation at the end-of-semester Solstice performance, where staff and students alike will gather to celebrate the semester’s accomplishments and watch the children perform what they’ve worked on in Green Street classes.

Education Coordinator Sandy Guze looked back on her time at the center, noting that students developed not only academically, but also socially, with an environment that was distinct from public schools.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t have programs like Green Street, so oftentimes I found myself wanting to be creative, wanting to do these things and actually use my energy in resourceful ways, but not really having teachers that believed in me or not really having the school system’s support,” Hurlock recalled. “When we don’t have programs and we don’t have mentors and we don’t have teachers who actually believe in you as a kid, we’re seeing how easy it is to flounder, because confidence is not given to you. Empowerment is not given to you. Generosity is not given to you. We have to fight for those things.”

The NEAT Task Force has set a self-imposed deadline for submitting a proposal to the city.

“If we cannot come up with a proposal that is sustainable and funded and all of these other things, we’re gonna lose the space,” Price said toward the end of the Nov. 1 meeting.

The University will no longer own the Green Street property when its lease ends on June 30, coinciding with the last day of the fiscal year.

For more information on the NEAT Task Force go to https://neatmiddletown.org/. If you are interested in getting involved with SOPHIA, contact Gabe Hurlock ’20 at ghurlock@wesleyan.edu.

Emmet Teran can be reached at eteran@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @ETerannosaurus, and Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply