c/o Danielle Cohen, Arts & Culture Editor

An artist who crafts a looming 30-foot sculpted spider and names it “Mother” should not be one whose works offer themselves readily to interpretation—and they don’t. Louise Bourgeois’ eclectic oeuvre of corporeal forms, oblong figures, and tactile structures does not translate into anything simple or explainable. To look at a work by Bourgeois is deeply emotional, alarmingly moving, and inexplicably soothing all at once. Her pieces convert familiar images into semi-abstract compositions and disarmingly eerie visions. Many of them are profoundly disturbing, drawing on Bourgeois’ difficult childhood and subjecting bodily forms to jarring reconfigurations. But there’s a strange beauty that runs through all her pieces, whether it’s through stunning hues of deep red, robin’s egg blue, and varnished gold, or rounded and arched lines suggestive of maternal comfort. Simply put, Louise Bourgeois’ work haunts and comforts.

In many ways, it’s precisely this simultaneity that Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait aims to portray—although, not in so many words. The show, which opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art at the end of September, watches Bourgeois employ an expansive range of mediums and explore an eclectic blend of themes that converge in emotionally saturated works. And through this lens, the lovely creepiness of her work becomes all the more potent.

Curated by Deborah Wye, the Chief Curator of MoMA’s Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, An Unfolding Portrait centers on Bourgeois’ two periods of active printmaking, one in the 1940s and the other in the 1990s and 2000s. The exhibit gives equal weight to each of the artist’s many mediums, aptly portraying her as a dynamic and astoundingly prolific creator who worked in everything from fabric and tapestry to bronze and painted wood.

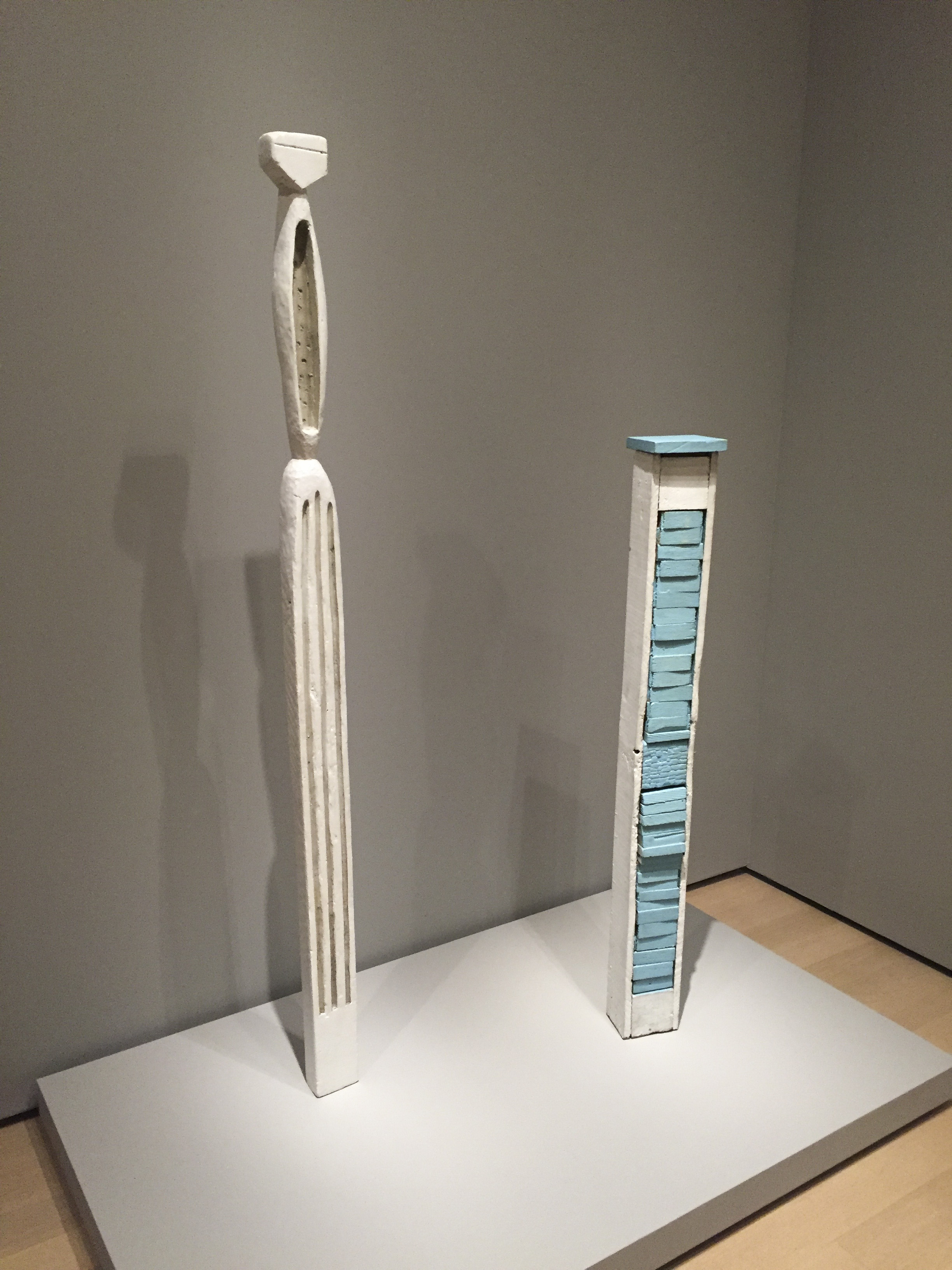

It’s also organized thematically, resulting in a somewhat disorienting temporal jumble of sculptures, prints, etchings, and illustrations that showcase the motifs Bourgeois kept returning to throughout her long career. The first, entitled “Architecture Embodied,” showcases architecturally inspired pieces where body and building become one, each structure—whether sculptural or two-dimensional—hovering somewhere between the human form and an architectural component. In a room called “Fabric of Memory,” examples of Bourgeois’ incorporation of fabric, which she began in the late 1940s, are on view. The space dedicated to “Abstracted Emotions” displays the works that are least grounded in realistic imagery. And so on.

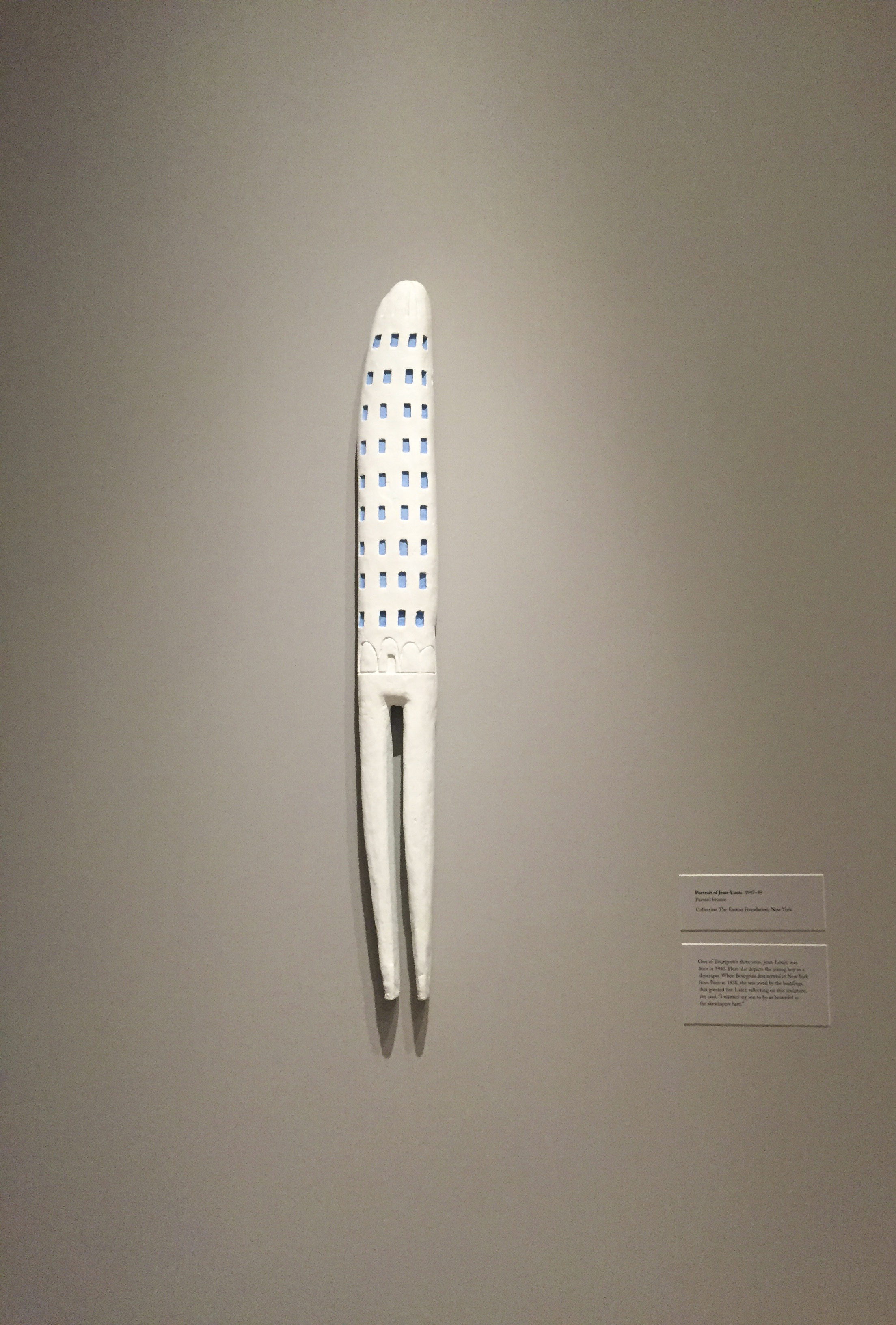

The main problem with this technique is that each category bleeds into the others. A piece like “Portrait of Jean-Louis” (1947-49), for example, a vertically oriented, three-dimensional form that hangs on the wall in the “Abstracted Emotions” room, could have easily been placed in the “Architecture Embodied” grouping, the two tapered lines that make up its bottom half strongly resembling legs and its grid of blue squares unmistakably reminiscent of the windows of a building.

In fact, throughout the exhibit, Bourgeois’ pieces blur the boundaries between person and building, melding bodies with architectural forms in ceaselessly novel ways. One installation piece, entitled “Cell VI,” employs a sort of micro-architecture to suggest a bodily absence, consisting of four human-scaled panels arranged in an open circle around a simplistic metal and blue-painted stool. Even the sleek black totems of “Forêt” (Night Garden, 1953) are clustered around each other in such a way that they could just as easily be a crowd of people—or even a tightly packed block of buildings—as they could a forest.

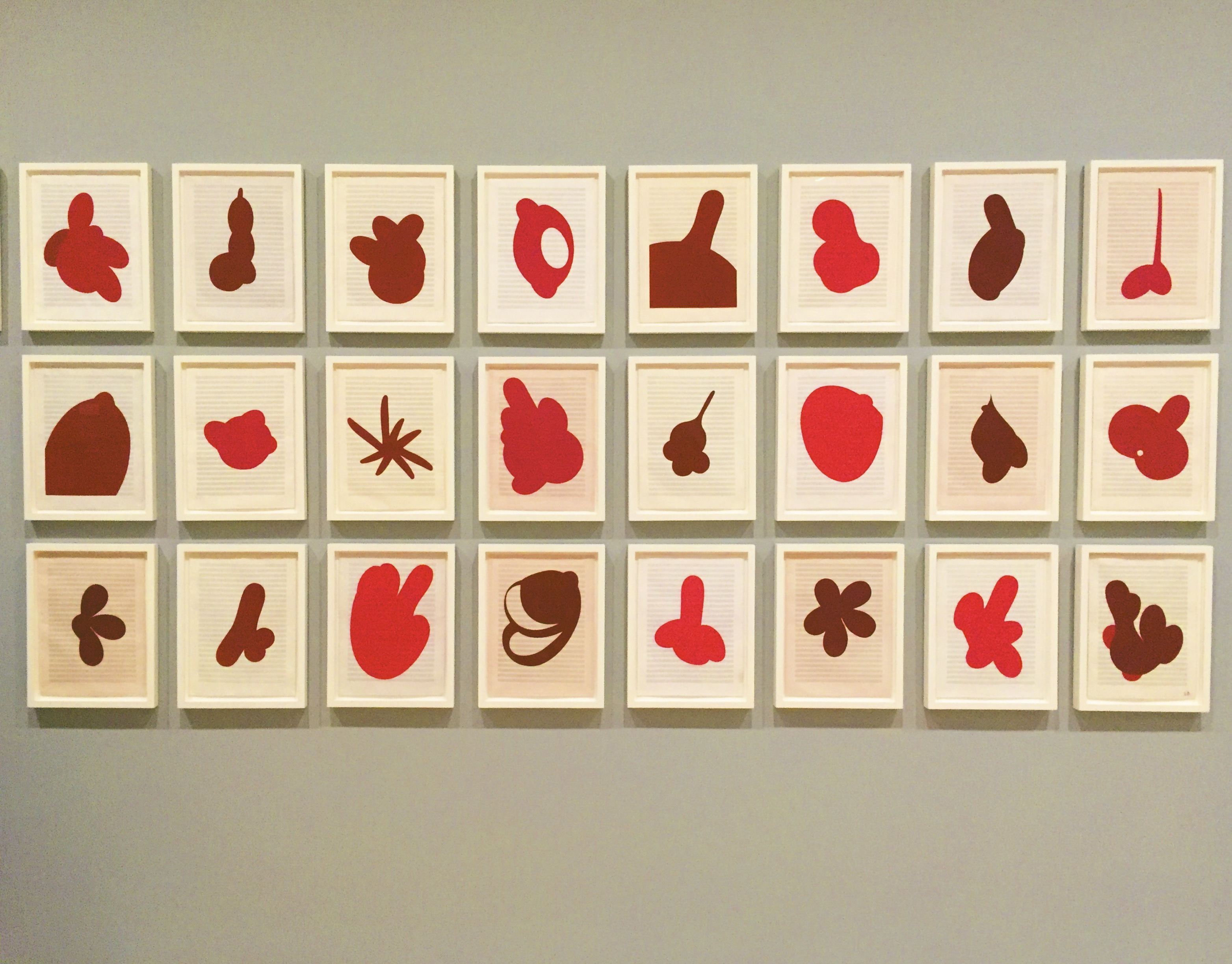

Despite the misleading organization, the sweeping retrospective is a stunning articulation of a body of work that truly defies categorization, jumping from material to material and weaving themes of femininity, motherhood, childhood, sexuality, domesticity, and nature into sharply emotional works that Bourgeois produced in reams. Perhaps its strongest piece is “Lullaby” (2006), a horizontal grid of 25 small framed screenprints in varying shades of white, off-white, and blush. Each is lined with a musical staff that serves as the backdrop to an amorphous shape, articulated in shades of bright cherry and deep maroon. No shape matches any other in the series: some strongly resemble body parts or pieces of the natural world, and others veer more towards blots of ink—or, if you take the color into account, blood. “Lullaby” is particularly illustrative of the playful darkness that permeates this collection, as well as Bourgeois’ work as a whole, infusing aesthetic appeal and light-hearted charm with sexual imagery and sinister implications.

The pièce de résistance of the exhibit is the towering “Spider” (1997), a 15-foot-tall spindly arachnid that looms over its viewers in eerie grandeur. Embedded in the spider’s abdomen is the ceiling of a large round cage that extends almost as far as the spider’s legs. Inside, a chair, a framed tapestry, and an assortment of odds and ends punctuate the sparse environment, and more tapestries, their edges roughly cut and fraying, adorn the outside of the cage.

The larger-than-life insect is located separately from the rest of the exhibit, which occupies the museum’s entire sixth floor, in the second-floor Marron Atrium, the first room visitors encounter upon reaching the top of the stairs at the museum’s entrance. High up on one wall of the cavernous room, another, smaller spider clings to the wall, and at eye level are hung a series of etchings, mainly from the late 2000s. These prints were executed using soft ground etching, a technique Bourgeois employed in her print works throughout her career that involves covering copperplate in soft, sticky material and applying pressure to the material wherever the artist wishes to make a mark. Bourgeois’ use of the lost wax techniques makes her lines, sometimes nervously jumpy and at other points fluidly rounded, appear as if done in pencil. The effect of the room overall is that it establishes a congruence between one of Bourgeois’ most iconic pieces and the prints around which the exhibit is oriented, a union of printmaking with the works that have come to define her public image as an artist—a union that the rest of the show aims to articulate.

Throughout her life, Louise Bourgeois frequently referred to art as a tool of survival, a way to guarantee her own sanity. Her works are deeply personal, tinted most visibly by her parents, particularly her father’s affair with her beloved English teacher, which her mother chose to ignore. Bourgeois is every much as present in her pieces as the materials through which she rendered them, her characteristic melding of darkness and beauty consistently present throughout every medium. It is in this way that her work becomes universal, saturated with psychic energy and quiet emotion, and occupying many extremes at once. Within each piece, pain and pleasure converge, and beauty and ugliness coexist. As her portrait unfolds, so does a panoply of dichotomous pairs, coexisting and cohering in one core-shaking image.

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait will be on view through Jan. 28, 2018, at the Museum of Modern Art.

Danielle Cohen can be reached at dicohen@wesleyan.edu.

- c/o Danielle Cohen, Arts & Culture Editor