The final lines of Cathy Colman’s “The Last Time I Saw Virginia Woolf” are as follows:

“I hate these men with guns.

But to be honest, haven’t I, all this time,

just been waiting

for the right river, the right weapon?”

Colman’s poem is one of the many forms of expression featured in Up in Arms, a new exhibit at the Zilkha Gallery that opened on Friday and features a wide variety of artists and work. Organized by guest curator Suzanne Slavick, Up in Arms examines the role of guns and gun control in American culture and mythology.

Walking through the gallery, one is immediately struck by the vast diversity in materials used in the show. A collection of wooden sticks hang next to giant film screens, and poetry shares space with crochet patterns.

“[The diversity in mediums] makes the show–at least from my end of it–more engaging, because you see the idea of different approaches, different viewpoints, it makes it seem more like a conversation rather than if it was all painting or all video works,” said CFA Program Manager, Rosemary Lennox. “There’s sort of this diverse idea that feeds into the idea of a discussion.”

Each featured work facilitates a dialogue that centers on the topics of gun use and violence. Joshua Bienko’s “Zwuernica” is a good example of this. The piece shows an ad for the 2010 film “Killers” layered with painted pieces from Picasso’s “Guernica.” By alluding to this classic antiwar painting while simultaneously portraying Ashton Kutcher wielding an assault rifle, Bienko shows that not all destructive violence takes place in war zones. Far too often, violence exists on our own TV screens, packaged as entertainment.

Other pieces, like Jessica Fenlon’s “Ungun,” seek to remove the power of guns by rendering them unrecognizable. Fenlon selected hundreds of images of guns from the internet and obscured them using glitch techniques, distorting them to the point where viewers would have difficulty recognizing them as objects of violence.

Susanne Slavick curated the show and was responsible for weaving a unifying thread through the wide range of pieces featured. In her opening remarks during the reception, she shared a series of statistics about guns and violence, including the particularly troubling fact that two-thirds of women in shelters who have carried guns have had those guns used against them. Slavick also discussed the relationship between written fact and images.

“We can read and be swayed by a lot of textual research, but I think images act on us in a different way,” she said. “I want both to act on us. I want the work and the language that surrounds it with the didactic material to get people to think and feel in different ways.”

The collection of still images, film, and literature Slavick put together created a jarring effect, causing the viewer to reexamine the role of guns in our culture. Up in Arms is a show that sparks sociopolitical dialogue on a scale much larger than the gallery itself.

“It’s something we are not united on, so anything that we can have a conversation about, anytime we can bring the arts into the conversation of something of such large social concern, I’m happy to make that happen,” said CFA Director Sarah Curran.

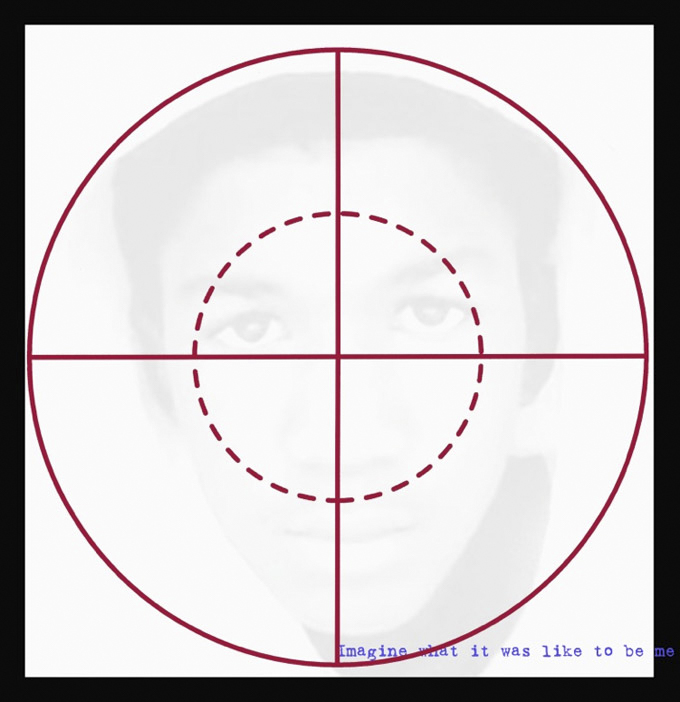

Up in Arms also includes a number of tribute pieces dedicated to victims of gun violence. One of the photographs featured in the show, Adrian Piper’s “Imagine (Trayvon Martin),” shows a black and white image of a young black man fading behind a bright red scope, with the words “Imagine what it was like to be me” in blue typewriter font at the bottom. This is not the only elegy in the show. Andrew Ellis Johnson’s film, “Massacre of the Innocents,” memorializes and mourns the life and death of Tamir Rice. It juxtaposes images of children’s toys with those of targets and bullets. When the target appears, its numbers face backward, giving the effect that the bullets are coming at the viewer, threatening any sense of safety. These works are simultaneously mournful and cathartic, with tones of protest running through both.

“Most of these artists are engaged with contemporary inequities in society in one way or another, so that is what I think motivates their larger bodies of work,” said Slavick. “As all artists have done, they either mirror the world as they see it or they project how the world might be.”

Some of these pieces do, in fact, imagine a better world. Jennifer Meridian’s piece, “A City Without Guns,” displays wooden sticks resembling pistols and rifles mounted on the wall. Slavick points out that the title could be interpreted as an allusion to the notion of a “City Upon a Hill,” an achievable utopia—a model for all societies. Meridian observes the world as it is and projects what it could be. In this way, the exhibit is not only one of grim violence, but of potential hope.

In many ways, Up in Arms is an apt exhibit to feature at Wesleyan, especially in the context of the larger political dialogue surrounding guns and gun control.

“I think the campus culture here is very social activism-friendly, and so I feel that this is an exhibit that is really relevant and current to what’s going on in the political climate right now,” said CFA Program Coordinator, Ariana Molokwu.

It is undeniable that Wesleyan students tend to stand up for change and fight for social and political issues, and this show very much functions as a springboard for that activism.

“I jumped at the chance to do something because it’s such an important topic right now,” said Curran. “Unfortunately, it’s an important topic historically, and it’s an ongoing conversation that is embedded in the American society and psyche.”

Up in Arms offers an insightful extension of the conversation regarding guns, violence, and the American identity. The exhibit will be on view until Dec. 10.

Mae Davies can be reached at mdavies@wesleyan.edu.

This article has been updated to reflect that “City Upon a Hill” was not a reference deliberately expressed by Jennifer Meridian but an interpretation offered by Susanne Slavick.

Leave a Reply