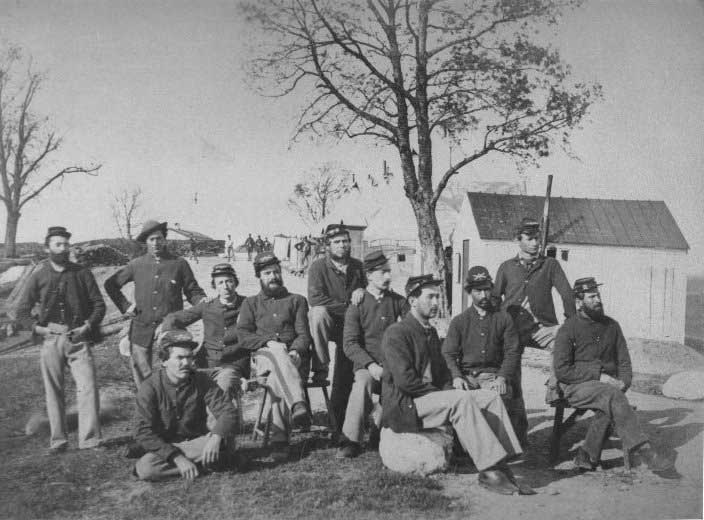

c/o americancivilwar.com

In recent years, higher education has been forced to reckon with a history of systemic racism that has plagued many of the country’s most esteemed institutions. Over a dozen universities recognized their ties to slavery and the slave trade last year, including Georgetown, which sold 272 slaves to save itself from financial ruin in 1838. Confederate monuments at schools like the Universities of Virginia and Missouri have served as rallying points for white supremacists. The Argus has written about the University’s own troubled history with racial politics in the past, focusing on the student body’s treatment of African Americans in the school’s first decades (Charles B. Ray, Wesleyan’s first Black student, left the University in less than two months after facing “heartless prejudice” and discrimination). Wesleyan’s first three presidents, Willbur Fisk, Nathan Bangs and Stephen Olin, were members of or were affiliated with the American Colonization Society.

So how would a student body that the famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison once called in 1835 “one of the strongholds of Southern despotism” respond when the Civil War tore the nation asunder in 1861?

Research by historian David Potts in his work “Wesleyan University, 1831-1910: Collegiate Enterprise in New England,” as well as related materials in the University’s Special Collections & Archives and Civil War blogs, sheds light on the Civil War experience at Wesleyan. While University students had been openly hostile to their African-American classmates in past decades, it’s unclear whether their almost uniform support for the Union reflected evolving views on race (student activism for abolitionism did intensify in the 1840s), or the reinforcement of other preexisting regional and political proclivities.

c/o bradleyfoundation.org

According to Potts, debates over slavery became increasingly prominent in campus political discourse by the 1840s. Richard S. Rust, Class of 1841, “met part of his college expenses as one of the first antislavery lecturers in Connecticut” and published a book of essays and poems advocating emancipation that included two contributions from Garrison. After the Whig Party disintegrated in 1854, campus political life became increasingly focused on the fracturing of the major national parties and racial politics. Accelerating tensions between the North and South was a central point of contention during the 18th presidential election in 1856. The contest pitted John C. Fremont’s anti-slavery Republican party against James Buchanan’s Democrats and an American Party (known as the “Know-Nothings”) who relied on anti-immigration and anti-Catholic invectives.

“As the North-South conflict deepened, students followed the Buchanan-Fremont presidential contest in 1856 with great interest,” Potts wrote.

c/o wesleyan.edu

On April 12, 1861, the Confederate Army fired the first shots of the Civil War in the Battle of Fort Sumter. The attack “elicited an immediate outpouring of Unionist support” on campus. President Joseph Cummings, Class of 1840, and student body leaders gave a series spontaneous and patriotic speeches, and the Wesleyan University Guards began organizing drills. Cummings, a Methodist minister who served as Wesleyan’s fifth President from 1858-1875, was a “powerful pulpit orator” who imbued his speeches with a “thoroughly practical and evangelical quality.” On the Civil War issue, Cummings was particularly compelling to a student body that hailed principally from New England and largely favored the Northern cause. While the University’s energized students appeared ready to defend the Union, unsurprisingly, their parents’ spirits were far more subdued.

“Receipt of letters from worried parents, however, tempered Cummings’ subsequent talks,” Potts wrote.

Once University students received notice that enlistment required a minimum of three years of service, their enthusiasm dissipated and volunteer numbers declined. Still, 14 students signed up that spring, joining a group of volunteers from Middletown and the surrounding area to form the core of Company G, Fourth Connecticut Infantry, who were assigned to the First Connecticut Artillery. The artillery regiment later fought in critical battles at Gettysburg and Fredericksburg.

Over the course of the next two years, Wesleyan students enlisted with growing frequency, particularly with units in their hometowns. In total, 298 Wesleyan students fought in the Civil War, from class years between 1835 and 1877. Thirty-two percent of the student body entered active service during the period, a percentage Potts believes likely exceeded participation from students at Amherst, Williams, and Yale. While Union support was dominant, about 24 students served in the Confederacy and at least one achieved the rank of General. Thirty-one students died during the war, only one of whom, Milton Butterfield, was a Confederate soldier.

The University’s flexible student-leave program was designed to account for students who decided to take absences for employment-related or religious matters. As a result, University enrollment during the Civil War remained stable (from 138 in 1858 and 135 in 1859, to 150 in 1861 and 1862, and 132 during 1863).

- c/o john-banks.blogspot.com

c/o john-banks.blogspot.com

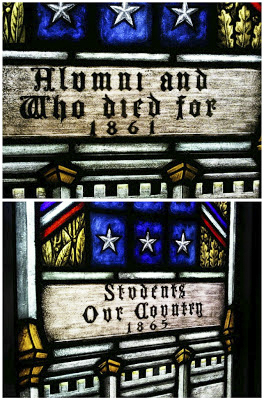

In 1871, the University decided to commemorate the memory of 18 of the University students who died during the Civil War by emblazoning their names on the stained glass windows of Wesleyan’s Memorial Chapel. George Crosby is one of the students whose name is prominently displayed in the church. Crosby, who was a second lieutenant in the 14th Connecticut Regiment, was 19 when he died after fighting at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862. Crosby was “eager to enlist” in the spring of 1861 (perhaps he was spurred to action by one of Cummings’ speeches), “but friends apparently talked him out of it.” By the next year, after calls for greater military participation from public figures like Connecticut Governor William Buckingham and President Abraham Lincoln, Crosby opened a recruiting office in Middletown and convinced a group of men to join a company to fight.

“I feel it is my duty to go,” he wrote to his mother in a letter.

On Oct. 22, Crosby died after an unsuccessful surgery to treat a bullet wound he suffered at Antietam that punctured one of his lungs. Two days later, Crosby was commemorated at “one of the largest funerals ever attended” at Middle Haddam’s Episcopal Church. Many of his peers from the class of 1865 attended, as well as Cummings and University faculty.

The Civil War also impacted several seemingly unrelated aspects of University life, particularly debates over coeducation and Wesleyan’s financing of new capital projects.

The war was one of a series of unfortunate events that stunted the expansion of University infrastructure in the mid-1800s. Economic stagnation plagued University finances in the 1840s, and administrators had only begun to reduce Wesleyan’s debt and increase faulty compensation when the Panic of 1857 forced Cummings to suspend $50,000 that the University had raised for new capital projects. The Civil War further delayed crucial building plans and reduced the value of land in Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Tennessee that Wesleyan had recently sold. However, later in Cummings’ tenure, Wesleyan veterans and odes to patriotism were instrumental tools in the development of College Row, including the creation of Rich Hall (1868), the Memorial Chapel (1871), and Judd Hall (1871).

”The almost $70,00 for construction of Memorial Chapel came in response to appeals based on denominationalism and patriotism,” Potts wrote. “The Army and Navy Union, organized in 1866 by Wesleyan alumni who served on the Northern Side, solicited gifts for a chapel to honor the almost three hundred Wesleyan alumni who had served in the Civil War.”

One unintended consequence of the Civil War was its role in catalyzing debates over the coeducation of Universities nationwide, a conversation from which Wesleyan was not exempt. As the demand for workers soared and casualties mounted during the Civil War, both the number of occupations available to women and the need for women to support themselves financially increased. More women began to seek out a college education, and as a result of this exigency—as well as pressure from trustees and calls for the University to live up to its Methodist roots—women were admitted to Wesleyan for the first time in 1872 (although the policy was later rescinded in 1909).

How does student abolitionism and support for the Union effort, as well as the prominent role University students played in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, factor into Wesleyan’s complicated, often disreputable history on racial issues? President Michael Roth ’78 offered one method for preserving historical memory through scholarship and engagement from students and faculty.

“I don’t know the significant dimensions of Wesleyan’s finances or elemental constitution that were built through the nefarious, awful, disgusting institution of slavery, but I am confident that Wesleyan participated in some of the most horrible events in the 19th century,” Roth said in an interview with The Argus. “The most tangible evidence of that which comes to mind is the human remains of Native American tribes that are still possessed by the University, not because we want to possess them now (we’ve been trying to repatriate them) but because back in the day they were stolen from people who were regarded as subhuman. It’s disgusting, it’s horrible, and I think you learn from that history, but we can’t erase it. The guilt is not useful, but learning from history, and the University’s participation in racist and exploitive acts, I think that is useful. And there are professors here who teach classes in that and develop publications about it. And I think that’s really useful because, like other institutions in this country, we did participate in events that in other moments we came to view as horrific.”

Aaron Stagoff-Belfort can be reached at astagoffbelf@wesleyan.edu.

3 Comments

大病险

免费赠送三十万大病险和十万出行意外险,

一人有病,百万人均摊,微信扫码加入:

http://www.taotu.site/ztb.png

时间有限,欲入从速

套图网

不止一次的来,不止一次的去,来来去去,这就是这个博客的魅力!

健康网

学海无涯,博客有道!拜读咯!