c/o Mohammed Alneyadi, Staff Photographer

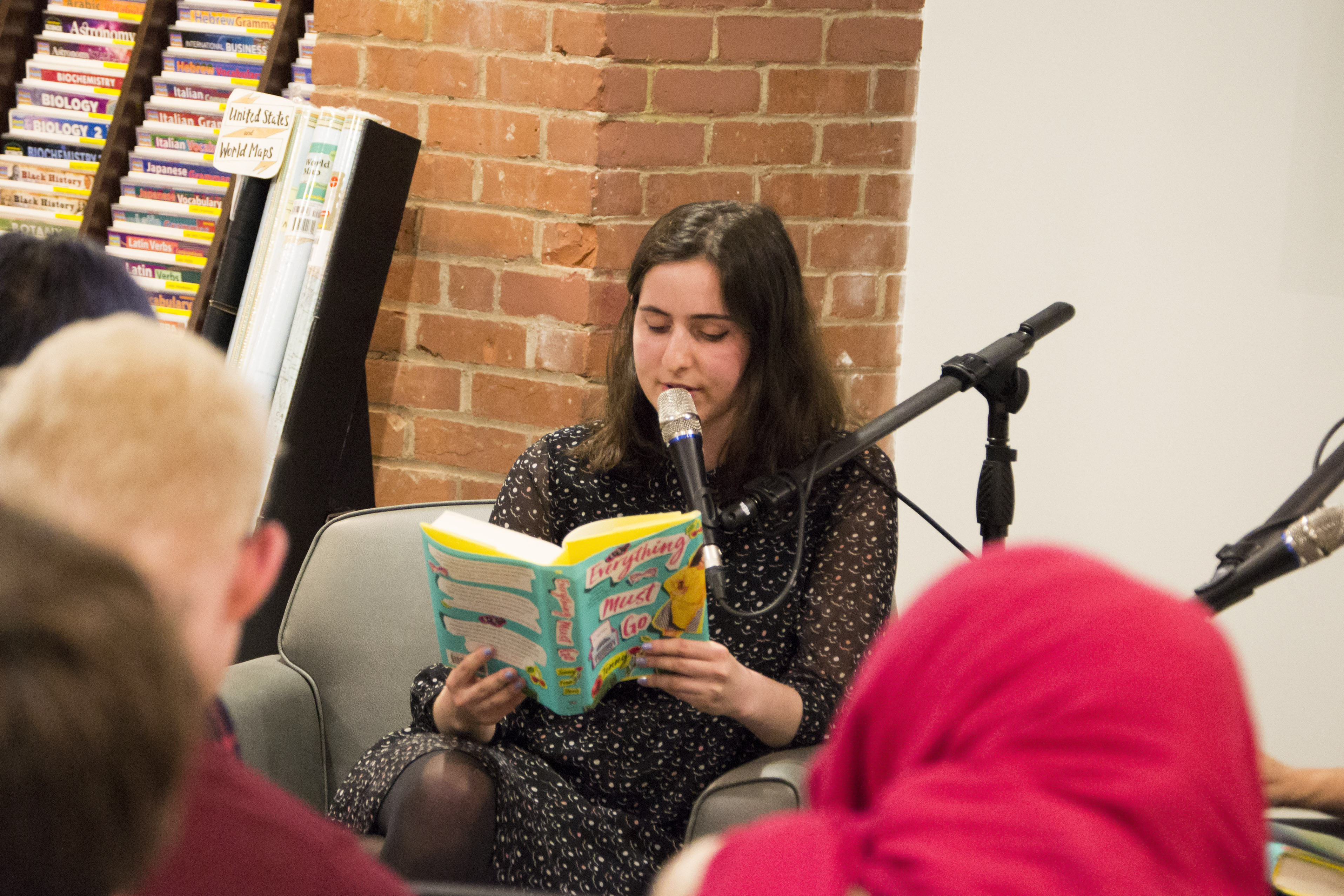

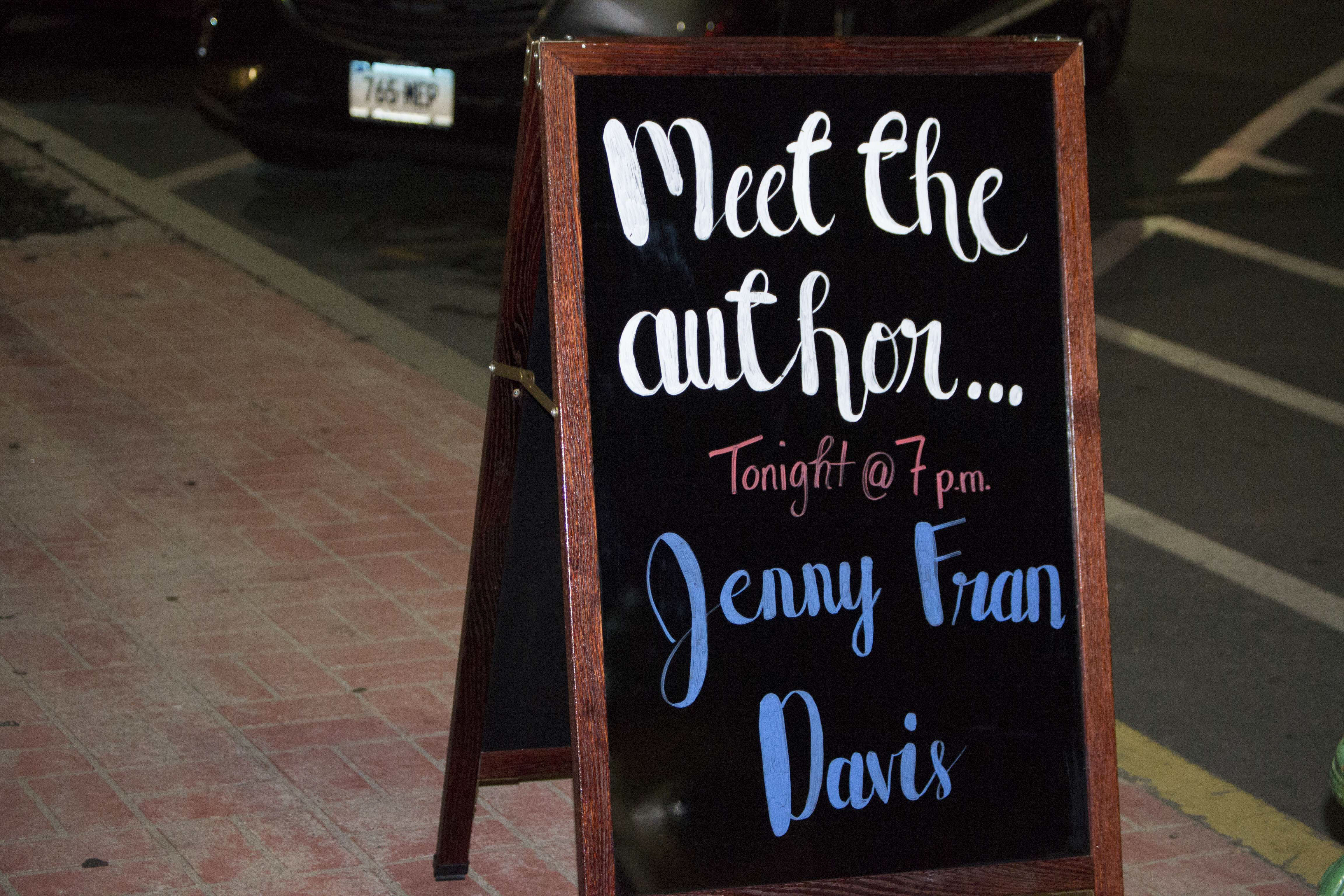

On Friday, Oct. 13, R.J. Julia hosted Jenny Fran Davis ’17, who discussed her first novel, “Everything Must Go,” which was released on Oct. 3.

Davis’ novel tells the story of Flora Goldwasser, a Manhattan girl who goes off to alternative boarding school, Quare, for her junior year of high school. When she is thrown into the progressive Quaker school in upstate New York, she must learn to adapt to an entirely new environment. Davis’ excessive tale satirizes and also embraces the political left.

“I can’t do justice to how gratifying it is to be introducing Jenny Davis tonight,” Associate Professor of English Sally Bachner told the audience. “Let me say that it brings me joy, true joy, to know that this is just the first of many times we will be gathered to hear Jenny read from something wonderful.”

Bachner, Davis’ former professor, then prompted Davis with questions on her work. The pair discussed the challenge of recognizing how much of fiction is consciously autobiographical and how much is an unintentional peephole into the author’s mind. This balancing game is particularly complicated for Davis, who wrote the first draft of the novel when she was just 18 years old.

“Even now, talking about it, I feel like [I don’t have] much authority on it,” Davis said. “I’m looking forward to understanding it better through talking about it…. One of my biggest anxieties around its publication is that I wrote it so long ago that it seems like almost not me. And I also feared that fiction was like a reverse Rorschach test, where my subconscious was going to be splatted onto the pages and some number of people could interpret it as something that was, although alien to me, really explicit and vulnerable on the page. And I still don’t really know if fiction is that or if I do have authority on it.”

Additionally, she joked about how certain components of the novel felt entirely out of her control. Davis, who is queer, addressed how the relevance of queerness in the book changed over time.

“It became way queerer as I rewrote it,” Davis laughed. “Like the name of the school—Quare—like totally subconscious, but talk about a reverse Rorschach test…. Once I signed with St. Martin’s [Press], you go through a lot of revision processes. And they send it to you with notes, and then you send it back with notes, and you keep exchanging it, and each time I got it, I just started making more of the characters queer. Like, each time, there’d be another lesbian thrown in, or another gay person of some sort. And I don’t know why; it just happened.”

Many portions of Davis’ story are based on her own life; she attended Woolman Semester School in Northern California for a single semester when she was in high school and worked at a Jewish camp for several years, both of which served as inspiration for the fictional Quare.

“A lot of the characters, initially, were based on people in a really inappropriate way,” Davis said, recalling the people from Woolman that many of the novel’s characters were originally based off of. “I guess I so shamelessly just used people as characters. I made them into caricatures, in a way, with very little remorse, surprisingly. I didn’t even think it would be published, so I just snatched funny things that people did.”

Davis also commented on the satirical nature of her book.

“It’s a totally excessive story, like it’s so over the top,” she explained. “And once you buy into it, you’re suddenly finding yourself buying into everything along the way…. But in terms of camp and parody, my biggest fear is people not understanding that this is satire. I guess [you should] never underestimate people’s lack of understanding.”

“We can miss satire, if it pushes our buttons,” Bachner noted.

“For me, the role of parody, humor, satire, camp, is creating these excessive, extravagant scenarios that provide clarity in order to look at things that are really happening,” Davis said. “Somehow parody can unlock real phenomena that we are a part of in a way that it’s hard to see when it’s so close and rendered so realistically, and so I think that having certain things be over the top in a way that seems like a light roast of white, liberal, progressive, crunchy-granola people ultimately reveals things about people who partake in those communities or participate in them.”

Davis also shared that she became more nervous about the satire in her book when President Trump was elected.

“Once Trump was elected, I kind of freaked out and was thinking, ‘Will this be a reference that’s even relevant to people who read it in the future? Is including this document in a way that’s anything less than completely earnest inappropriate?’” Davis pondered. “And I ultimately came to the conclusion that humor isn’t disrespect. There’s some sort of way that humor can work with activism and it doesn’t undermine activism. I think there’s a huge stereotype about how people in the left can’t laugh at themselves; they’re humorless. And I actually don’t think that’s true at all.”

She also chose to keep some parts of the book more realistic, allowing for readers to relate to protagonist Flora in a fundamentally human manner.

“The things that I chose not to satirize, not to make campy, were the relationships between people,” Davis added. “Those are my most earnest attempts at representing the reality of being a 16-year-old…. When we think of our future selves, we somehow think that we’ll occupy this all-knowing, competent, calm consciousness, like when you think of yourself at 30, or 50, or 70”—“Never gonna happen,” Bachner interrupted—“but maybe we can gain a little more understanding and archive all of these experiences,” Davis finished.

Bachner noted that she enjoyed the celebration of femme style, as shown through Flora’s love of vintage clothing and accessories. Quare has a policy of “no shell speak,” which means that students are not allowed to comment on each other’s physical appearances, which Flora initially struggles with in the novel. Davis talks about the link between one’s identity as a consumer and identity as a person, noting that the latter is often reflected in the former.

“I noticed this all-encompassing obsession with depth as opposed to fringy, shallow things,” Davis said. “The people who were obsessed with stripping away the fringes of life were also the ones who had turned so into themselves that nothing else seemed important. Its purpose is pretty clear: to give people a break from focusing on external things. But I think that you can strip away external things, and clothes and style can become irrelevant, but then how are the things that remain somehow essentialized as more of the person? I never really understood that. It seems like you can keep taking away until you’ve whittled someone down to nothing but this deep, peaceful, pond-like nothingness.”

Davis wrapped up the talk by taking a question from the audience about her second book, which is a part of the deal she has with her publisher, St. Martin’s Press.

“The protagonist of the second book is a more peripheral character in the first book,” Davis revealed. “And the books have something in common. They’re in conversation, but they’re actually very different—intentionally so…. Book 2 is more relevant to things that I’m currently thinking about, but also has things that I started writing a few years ago, so I think we’re gonna run into the same thing with that one, but I think it’s better to not have mastery over your work.”

- c/o Mohammed Alneyadi, Staff Photographer

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed