On Tuesday, Oct. 10, the English Department hosted a panel, in the Downey House Lounge, of two professors to discuss the question, “What is a book?” The panel was comprised of Assistant Professor of Italian and Assistant Professor of Medieval Studies Francesco Marco Aresu and visiting Assistant Professor of English Sam Fallon.

English Department Chair Stephanie Weiner opened the panel by introducing the two professors and the courses they will teach in the spring semester. Fallon will be teaching a course on British lyric poetry throughout the Renaissance, and a course on the history of the book as a textual medium. Aresu will be teaching a course on Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy” (conducted in English) and a course on Giovanni Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” (conducted in Italian).

Aresu opened his segment of the panel with two provisos. The first focused on his research regarding late antiquity and early modern Italian literature; the second emphasized that his approach to the text was mainly historical. Aresu argued that all literature can be understood based on the material aspects of a text’s history.

From there, Aresu proceeded to give an anecdote about a Jewish, female professor in Italy during the medieval period. The professor is remembered today for discovering a fragment of a hymn written by the Greek poet Sappho. Scholars believe someone unfamiliar with Sappho’s poetry dictated the fragment, so Aresu used the fragment as an example of a larger phenomenon.

“Books come in all sorts of forms, and [are] not always [the way that we think they are],” he noted. “[Books are] also not abstract texts; they have an embodiment and as such are subjected to many technological shifts.”

One such example is the shift from using a papyrus scroll to a codex, the type of book often published and read today. Aresu used an example of a papyrus scroll fragment of a Greek book on sex. A papyrus scroll, unlike a modern-day book, is wrapped around a cane, which can then be unfolded. The title of a text was not printed on the outside of a papyrus scroll, but on the inside of the scroll, something very different from a contemporary book.

“Because of the price of papyrus…and because it was difficult at some point to acquire the material for papyrus… we have a switch slowly from the 4th/5th century to the… parchment codex,” Aresu said.

Aresu proceeded to discuss manuscripts of Dante’s “The Divine Comedy,” a major text with varied manuscript productions. He spoke about a manuscript with pages located in Milan and Florence, and which featured extensive annotations on Dante’s text.

“We know that the poetic text is surrounded by commentary that is 20 times as extensive as the text…” Aresu said. “The format…is already telling you something [about the book]….”

Aresu used another example to show how manuscript reproduction often leads to new interpretations of the original text. This manuscript has no room for commentary, unlike the original, and presents an image of Dante sleeping. This image is a notable interpretation of the text, as it implies Dante dreamt the entire story of “The Divine Comedy,” when Dante had insisted that he had experienced the text as he wrote it.

Fallon picked up from where Aresu left off, discussing the ways in which a text can be interpreted differently depending on how it is published.

“It’s a strange and peculiar thing…and once we realize that books are how we get to texts, and we can no longer see the editions of the text, the thing, but rather it’s a particular book, this Hamlet, and it brings with it certain material things that shape [how we read the text],” he said. “It’s the text itself that varies [across different book editions].”

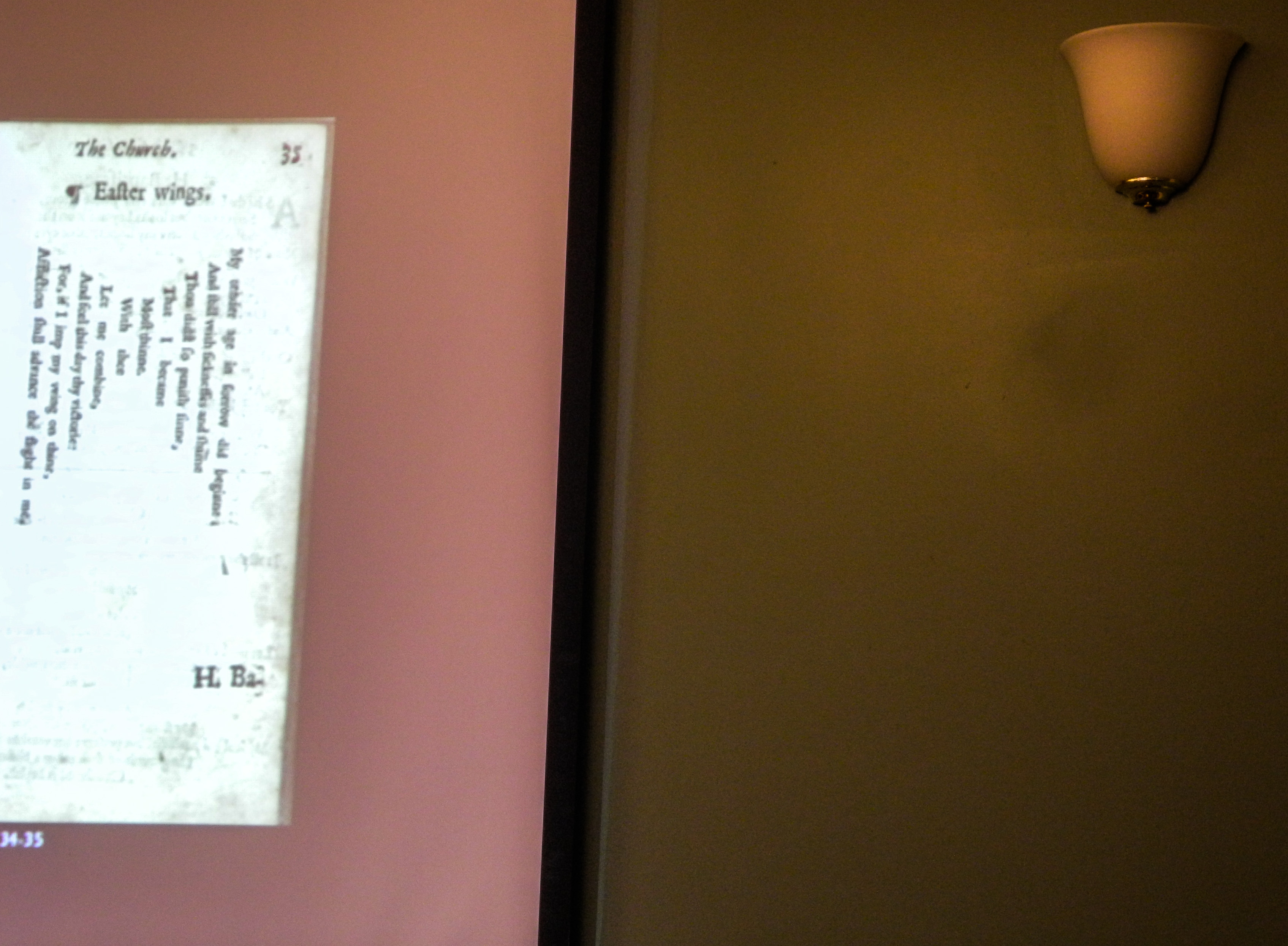

As an example, Fallon discussed the Penguin Classics edition of “Easter Wings,” a poem by George Herbert. The poem, in this edition, was printed sideways, an aspect of the poem that Fallon once wrote an analysis of. However, when researching the text, he discovered that the first printed edition turns the text counter-clockwise, as opposed to clockwise, and was also comprised of two pages as opposed to one. He also found an early manuscript version of the poem from Williams Library, with text placed horizontally, and words and phrases crossed out by Herbert himself. Thus, his original analysis of the poem no longer held up to scrutiny, as the poem structure he had analyzed was not created by Herbert but by later editors and publishers.

The panel then opened up to a question-and-answer session. One audience member asked if it is possible to “do violence” to a text by over-editing it.

“It’s a matter of the kinds of choices you’re making when you put together this monster hodgepodge,” Fallon said, referring to his Penguin Classics edition of Herbert’s poetry.

“The important part is to declare one’s own agenda…” Aresu noted. “I think it is a profoundly moral approach to literature to announce one’s own agenda and process.”

Assistant Professor of Letters Gabrielle Piedad Ponce-Hegenauer asked the panel about how translations of texts affect how they are reproduced and interpreted, such as the widely circulated 15th-century translations of the 14th-century Italian poet Petrarch.

Aresu noted that the work of Petrarch in translation is not the one that was initially read, partially due to ideas becoming lost in translation. Lots of elements like maps and portraits included in the initial text were lost over time. Aresu noted that intellectual history requires one to be aware of the material conditions of a given text.

Assistant Professor of Letters, Assistant Professor of Medieval Studies, and Assistant Professor of History Jesse Torgerson asked the panel if manuscript histories should be taught and explored, or if we should only teach the texts that we have now.

“I’ve often thought, in teaching these texts, if we set aside this desire…for the abstract text and embrace the medium we’re in…why not just teach this book as it, and not worry about [what is lost through edits]?” Torgerson asked. “In a sense, more people have read George Herbert in the Penguin edition [than others]…more people can share that than any other edition…Why don’t we embrace the moment we’re in historically?”

Fallon noted that studying the history of a text is useful to understand it better.

“Reading is about finding patterns… It’s not to say interpretation is impossible, let’s think about cultural history instead…it’s not to say the patterns are wrong but that we can [study it’s larger context],” he said.

Henry Spiro can be reached at hspiro@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter @judgeymcjudge1.

Leave a Reply