In “Crosstalks,” two writers sit down to discuss a book, movie, TV show, or piece of art they both feel strongly about. Sometimes they disagree; other times, they’re in perfect harmony. Today, Opinion Editor Hannah Reale ’20 and Assistant News Editor Emmy Hughes ’20 discuss the debut novel of recent Wes grad—and former Argus Editor-in-Chief—Jenny Davis ’17.

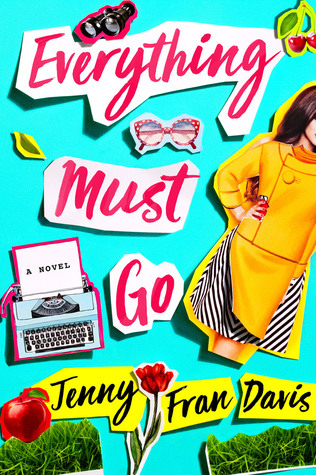

Jenny Fran Davis only graduated this past May, but she has already has a book coming out at the beginning of October. Her debut novel, “Everything Must Go,” centers around 16-year-old Manhattanite Flora Goldwasser, an old soul with an affinity for ’50s fashion. In her sophomore year of high school, she meets Elijah, a Columbia University student who is working as a tutor at her school. He’s a well-known indie photographer, and she agrees to let him shoot her—as long as her face isn’t shown. She goes by the pseudonym “Miss Tulip” and slowly falls for him over the course of the year. In order to be with him the next year—despite the fact that her feelings have gone unsaid—she transfers to Quare, a Quaker school that Elijah will be teaching at the next year. But there’s a catch: Elijah decides last minute that he isn’t going to Quare.

The true focus of the story, though, is Flora’s evolution over the course of her junior year, told through a series of letters, journal entries, emails, and transcripts. Elijah re-enters and leaves her life, and Flora emerges with a new sense of self.

We looked at Davis’ novel through four different lenses: the unique form of the book, Flora’s development while away at her Quaker school, the role of fashion and feminism in the story, and how this book stands apart from the rest of its genre.

Flora in Form

Hannah Reale: One of the things that struck me about the novel was that, after about 70 pages, you realize that it’s going to be told through letters, and you have to switch modes of expression. I expected it to be jarring and somewhat difficult to read, but it was actually really easy to switch through these different perspectives and gain a real sense of who Flora is through these letters, report cards, transcripts, and everything else.

Emmy Hughes: Yeah, there’s a cool temporal difference between the Flora who’s compiling all of the things that you see through her typed-out “Oh, look what I was like at this time” and also through the physical evidence of her letters and conversations with people. And I really like that dynamic throughout the book. I also like the use of letters and emails and journal entries as the way of telling a story. I thought that was a really interesting method of narration, and also a more insightful method of talking about Flora and seeing who Flora is that might have otherwise been obscured.

HR: It really tricked me because I could feel the difference between Flora’s voices; if she was writing a letter to one of her friends from home or to her sister, I could sense that. That was so incredible to me because, in a book, you really want to be getting inside the protagonist’s head. That’s kind of the point of reading novels to me, to relate to their experiences and motives, and being able to see so many facets of her through the different ways that she addresses different people in her life is so fascinating.

EH: Yeah! And I think there’s this really cool difference between the way that she uses her journal and the way that she interacts with people in email form and in letter-writing form. It’s a different format for her: in the journal, you get the very deep, real emotions that she’s trying to express about Elijah and these very personal thoughts and feelings. But you also get the somewhat performative conversations where you’re reading the letters, because you’re only seeing the side of her that she presents to whoever she writes to. And also that we get people answering to her. She’s not just the title character whose first-person narration we get in the story, even though she’s compiling everything.

HR: And we also get a hint about what those characters are like when they’re not around Flora, which we usually wouldn’t get in a typical first-person novel. And then sometimes there are time gaps, which you can see when you look at the dates of the letters and journal entries. Like, we don’t really see what happens over her winter break, we just get letters from her friends that say, “You were acting weird over winter break,” or a journal entry from, like, a month and a half later. So it’s not like we’re completely inside her head.

EH: There’s this really interesting portion, right after the Elijah event, where she’s pretty much absent from the narration, so you’re learning about her via other people’s conversations and it’s really cool because you feel the weight of that absence, and that just brings more weight to the thing that she’s struggling with. And you’re seeing how people react to that.

HR: And it’s almost like, in that moment, she’s absent from herself as well, which is what lends so much power to it because she really doesn’t feel like herself—she doesn’t know who “herself” is—and we learn about her through other people, but we’re not hearing about her development from her.

EH: Right—you’re witnessing people’s processing of her evolution. It’s a cool way of doing that, that can only be done in this form.

HR: And also, I really like that she couldn’t use her phone because I feel like there’s this sort of association that comes with texting that we don’t get here—and maybe this is me being a sort of weird purist when it comes to technology—but I feel like that really would have changed the narrative that we were given. And I didn’t want that, I didn’t want the constant communication. We’re seeing Flora’s curated self, whether it’s to herself when she’s writing in a journal, or to a person when she’s writing the letters.

EH: Not only does the lack of texting allow for long-form writing, but also texting is associated with this very quick “get it out of my head immediately” mindset. It lacks the thoughtfulness that goes into something like a letter, and you can really see that in the book. It’s the compiling of all the elements into this book that’s as much an art form as the things that make up the elements.

Flora Flourishing

EH: When Flora begins to push Elijah away, and as she’s becoming more open, becoming friends with Sinclaire—who I LOVE by the way—and getting to know Agnes and Juna, I felt like I wanted a more fleshed out journey. So I was just wondering how you felt at the end of the book with her relationships with Agnes and Juna? What did they serve in the plot?

HR: I kind of like having these little anecdotes that can mark for us how she has changed, with Agnes or Juna with the pot brownies, or with the pond. Her desire to go deep, her desire to fit in with this community she initially felt so isolated from, and to see her assimilation there. And I agree that I felt like we could have gotten more insight into her head during those months of recovery from Elijah.

EH: I see your point about each of these things culminating as an indication of her change over the course of the novel. Weirdly, maybe what I was looking for was her going from being so crazy about Elijah and to becoming into another person at the end of the novel. But in reality, it was “Elijah, Elijah, Elijah,” and then all these other relationships that she had changing and shifting, with Sam and her mom and Juna, which in a way I think is a very important part of this book—as she’s taking distance from Elijah, she’s allowing all these other people to enter her life.

HR: I also liked that. I feel like in so many YA novels at the beginning, we’re supposed to like the dreamy love interest, but I never felt like I was supposed to like this creep. I would be drawn to this book when I was slightly younger, like 15 or 16, and when I was that age it would have been very confusing for me to feel forced into liking this obviously predatory character. And to not have to like him…like, he’s most often described as looking like a bird. Birds are not hot! It was so refreshing to be able to hate him from the beginning and to see Flora change her relationship with him over the course of the novel.

EH: On the topic of comparisons to animals: the “swanlike” comparison that Elijah makes during the sex scene? I was like “What IS that!”

HR: (Laughing) Yeah, like get the fuck out of here!

EH: Can you imagine, you’re having sex, and he suddenly says to you: “You’re such a swan…”

Like what??

HR: (Still laughing)

EH: What a weird metaphor!

HR: He so obviously doesn’t get her in any way shape or form, and that’s summed up so well in this one metaphor. In the beginning of the book she pegs him so quickly, she’s like: “He looks like a bird!” and then when he’s like “You’re a bird!” she’s like “No I’m not! Fuck off!”

Flora’s Feminism and Fashion

EH: Another question that I had, stemming from the aspect of feminism and identity in this book, was the role of fashion. And how there’s this fairly large focus on it later on in the book as she gives away all her clothing items and becomes more assimilated to Quare. How much of that is her fitting into the mold of the Quare student and how much of that is her finding her own identity? How associated are clothes with who she is and with feminism?

HR: At the beginning of the second semester, I think she just wants to disappear. She doesn’t want to be the girl that’s in the apricot dress anymore. She wants to just be in her oversized sweater and just walk around—and it doesn’t help that so many people on campus are just pointing to her like, “There’s a girl who’s a victim. There’s a girl who we can help.” I think she is attempting to disappear and, in its relation to feminism, it’s absolutely her right to explore her identity in all these different ways, but her having her clothes or not having her clothes doesn’t really change her identity as a feminist.

EH: Yeah, I totally agree. I think I felt slightly differently about the performance of removing the clothes and putting them in the vending machine though. I think part of that was certainly more of an assimilatory thing, but also it was a means of coping and a means of turning the pain that she was experiencing something that had real, tangible artistic effects. She was using her singular experience as a proxy for an overall, universal idea: What is sex? Is it a transaction? But she doesn’t fully know.

HR: And when she gets interviewed on NPR, there are all these quips where Flora says, “Well, I have this vending machine. It has a meaning. I don’t really know what the meaning is, but I’ll find it.” And I loved it because, whenever an artist goes on for six minutes during an interview about how they thought through every single meaning, I don’t believe them. And it felt so much more realistic than all of those actual, real-life interviews that people give!

EH: That’s so true! There was this really interesting level of authenticity in that fake NPR article that you oftentimes don’t get from real interviews. Because I’ve listened to that exact podcast in the past, and not only did Jenny seriously capture the style, she also used it as an amazing avenue into how Flora responds to her own creation and how she sees it. It was super well done, and it was authentic in the sense that she didn’t fully have an idea of what she was doing.

HR: I expected her to have a little bit more of a freakout when it came to her newfound fame, because her alter ego Miss Tulip blows up and she’s like “I don’t care, I’m in love with Elijah!” and then her vending machine art piece blows up, and we’re not really in her head at that time either, so we don’t get to see her freaking out. Other people are writing her letters saying like, “OMG this is so incredible,” and she’s just like “This was so fine, it was an interview on NPR, no big deal,” and this is something that, even though she’s struggling in her second semester at Quare, it feels like this would be something that would be affecting her more—this level of attention.

EH: Absolutely. There’s no point in the novel where we get this direct insight. No journal entry that’s like “Oh my god, I am all over Nymphette Magazine, I am THE face of the alt-fashion-New-Yorky movement.” And if I was journaling, I would talk about that all the time! But instead, Flora avoids talking about any of the effects this fame has on her. You would think you would see more of this, but we don’t.

Flora Falling in Love

HR: This book made me want to break my rule of not writing in or underlining books that I read for pleasure because there were so many specific lines that I wanted to remember. There was one that I just kept turning back to: When she realizes that falling in love with Elijah was just falling in love with the idea of him.

EH: That also resonated with me, falling in love with an idea.

HR: And I just thought that what this book did so well and so accurately is that it really captured the vulnerability of becoming and being a woman. There’s an inherent vulnerability in having to go these really difficult times of being unsure of your identity, and also the world wanting you to fail, to some extent. And it really does an excellent job of just exploring that. This is the YA novel I wish I’d read when I was 14, because so many books are all about the process of the girl falling in love with the slightly older, mysterious, probably tall guy that has his own unique style, and when this book started, and I was afraid that this was going to be that. But then she goes to Quaker school in the middle of nowhere, and she can’t use her phone, and the book was immediately going in an entirely new direction.

“Everything Must Go” will be available on October 3rd. Davis will be coming to RJ Julia on Oct. 13 to promote her novel.

Hannah Reale can be reached at hreale@wesleyan.edu.

Emmy Hughes can be reached at ebhughes@wesleyan.edu.

Leave a Reply