Camille Chossis, Staff Photographer

On Wednesday night, the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life hosted “Commemorating and Protesting White Supremacy” in the Memorial Chapel. The Center’s “Right Now!” Series hosts events responding to breaking issues in public life. Professor Crystal Feimster of Yale University and University Professor of History, Demetrius L. Eudell spoke.

Crystal Feimster is an Associate Professor of African American Studies, History, and American Studies at Yale University. She specializes in racial and sexual violence and is currently completing a project on rape during the American Civil War. Eudell was recently appointed as the History Department chair. He specializes in the history and culture of slavery, abolition, and emancipation in the Americas.

According to publicity fliers, the discussion aimed to shed light on “the historical significance of Confederate monuments and the campaigns for their removal in New Orleans, North Carolina, Baltimore, and elsewhere.” Its topics ranged from the historical context in which Confederate monuments were erected to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Feimster began by asking what is at stake for the communities closest to these statues, or what is at stake when President Trump tweeted that efforts at statue removal were erasing history. Eudell posed the question: what work are the monuments are doing? One of the functions, he says, is to obscure the reality of slavery and racial oppression in American history.

The conversation touched upon President Obama’s perceived inability to unite the nation on the subject of race relations, statues which commemorate Christopher Columbus, and how flawed a public figure needs to be to justify the removal of their statue.

On the topic of flawed figures, Feimster lamented the incomplete stories which monuments tell.

“So then the question is, What are we celebrating when we commemorate people who fought and died for the institution of slavery?” Feimster said. “We have to call it what it is … That is the problem with the monuments, in fact, is that they’re doing the work of erasing history because they want to tell one story, the one we want to celebrate. And when we say ‘we,’ I don’t mean me.”

A number of recent events in the U.S. has spawned debate over the removal of Confederate statues and symbols. In June 2015, a white supremacist killed nine African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina. On Aug. 11 of this year, white supremacists, white nationalists, and neo-Nazis gathered at Emancipation Park in Charlottesville, Virginia. Some were armed and chanting racist and anti-Semitic slogans. The next day, a man with alleged white supremacist sympathies drove his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing one person and injuring 19 others.

c/o wikipedia.com

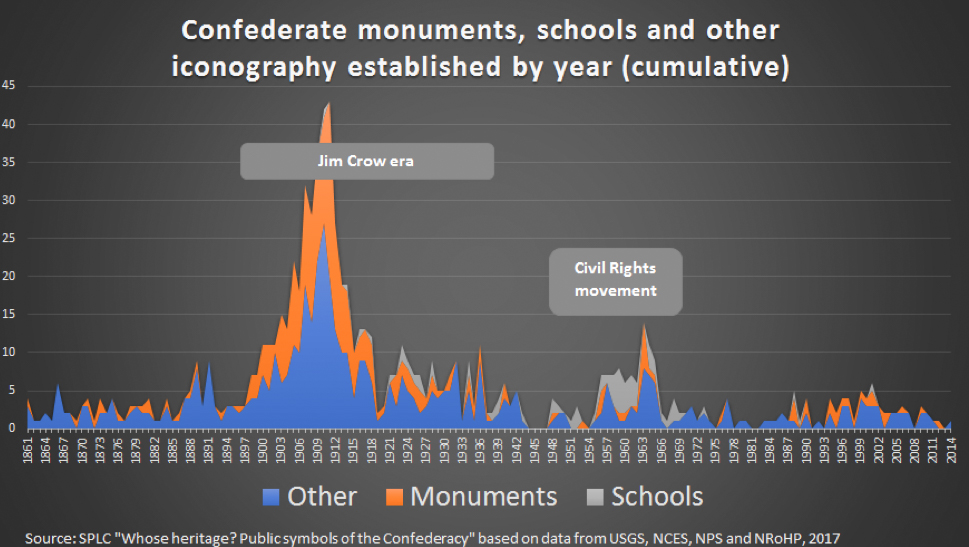

Eudell later mentioned that Confederate monuments were built at the fastest rate during the Jim Crow Era and the Civil Rights Movement. Following the Charleston mass shooting, the Southern Poverty Law Center launched an effort to catalog public commemoration of the Confederacy. It found, among other things, that 10 U.S. military bases, 80 counties and cities, and 109 public schools are named after Confederate icons. At least 718 Confederate monuments dot the country, and they are usually, but not exclusively, are erected in former Confederate states.

At one point, Professor of English Lois Brown asked about former sites of Confederate Monuments and their potential to continue terrorizing African Americans. Feimster responded, emphasizing that the communities of each site must decide for themselves the new character such sites will take.

“What does it mean for those people who have lived their lives and told their children and grandchildren that their great, great grandfather was a Confederate?” Feimster said. “How do we reckon with that?”

To her, white people will have to start putting in an effort to reconcile and to own their past of racial dominance.

“They’re going to be haunted by great, great grandfathers who owned slaves–in the same way, that some of us are haunted by great, great grandfathers who were sexually assaulted and raped…” Feimster said. “And that’s hard.”

Eudell echoed the difficulties which will come from efforts at true racial reconciliation in the U.S.

“The real hard work is after the monuments come down,” Eudell said.

Brandon Sides can be reached at bsides@wesleyan.edu.

-

沃八达