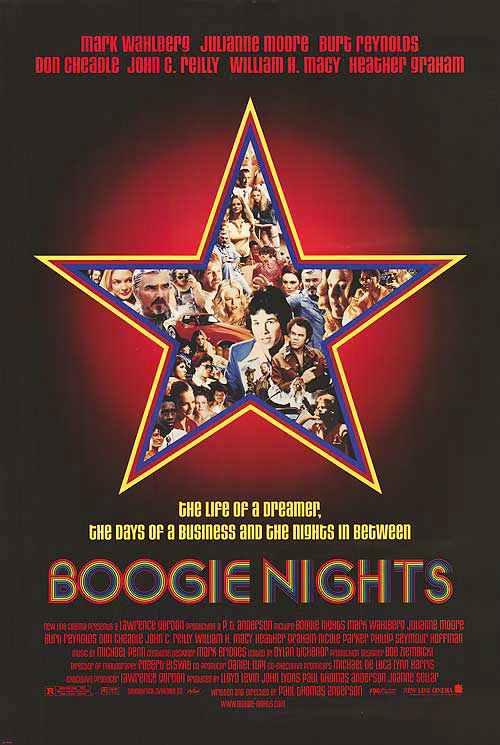

c/o moviposters.com

Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Boogie Nights,” (1997) which played last week at the Wesleyan Film Series, presents a world so overtly lacking in political content that, on its face, it may seem out of touch with a contemporary audience, entrenched within a pop culture that cannot escape the political realm. However, this reading of the film would be overlooking the work’s subtleties, which reveal an underlying warning about the effects of apoliticism: the absence of civic consideration ultimately becomes the political message. Within Anderson’s depiction of the enthralling yet extremely dark netherworld of the pornography industry—obsessed with body image, exercise, and sexual adornment; plagued by drugs, violence, and narcissism—it is no coincidence that the only political imagery we see is a portrait of President Ronald Reagan, the only president (at the time) to come from the entertainment world. The image of Reagan is never addressed but hangs omnipotently in the background of every shot of a harrowing courtroom scene late in the film. This moment, where the presence of political power is blatantly ignored, concretizes one of the film’s central themes to investigate the values and cultural forces reflected in the extreme subculture of the entertainment industry, which lays the groundwork for the rise of Reagan.

“Boogie Nights” begins in 1977 and tells the story of teenager Eddie Adams, a high school dropout with a troubled family life and a dishwashing job at a nightclub. While Adams may lack certain intellectual faculties, he says that “everyone is blessed with one special thing,” and for him, that thing is his good looks and abnormally large penis. Porn director Jack Horner eventually discovers Adams, who then runs away from his middle-class home to live with Horner and become a porn star. He meets Rollergirl, also a teenage actress with whom Adams has sex in front of Horner as his audition, along with porn star Amber Waves, who acts as a mother figure for Adams in a very oedipal fashion. Adams is adopted of sorts by Horner’s cast and crew, taking on the name “Dirk Diggler,” and immediately becomes a huge sensation. In the porn world, Diggler finds a community that he can identify with, friends with whom he can discuss protein powders, exercise regiments, and Italian clothing. Most importantly, he situates himself in a social scene where he is the king, attaining some sense of control. While consumerism, sensualism, vanity, and drug addiction certainly define the culture, Horner and Diggler share an artistic vision. They feed off each other’s ambition and connect over a common sentiment that porn shouldn’t just be treated as something to get off to, but rather as an art form.

Just as quickly as Diggler rises to fame, he falls. He becomes addicted to cocaine, which leads to bouts of erectile dysfunction. Then their new films start to bomb. In a fit of frustration, Diggler screams at Horner, who has found a new teenage star, and then quits, spiraling into abject poverty and manic schemes to steal drugs. Diggler ends up where he started, jerking off for money until he’s beat up by a group of kids who scream homophobic slurs at him. Poor, hungry, and homeless, he returns to Horner, whose career has suffered since Diggler left, and they embrace.

In a mere plot line analysis and summary, it is difficult to capture how unbelievably funny the movie is, especially the character of Dirk Diggler. While the film displays the ironic and self-referential tropes of ’80s and ’90s cinema, Paul Thomas Anderson uses these mores to question what exactly it is about the movie that we find so comical, leading to an even darker realization about our complicity in the despair depicted in the film itself. The reason why we laugh at these characters becomes a key element in Anderson’s broader commentary on porn and irony in the film, which fittingly came out a year after “Infinite Jest” was published, in the era where the first murmurs of new sincerity started to appear. Our amusement goes something along this line: Diggler and his circle of friends admittedly are not very bright. They spend their days lifting weights, snorting cocaine, and having sex. They live, by most standards, empty lives. But the ironic humor arises with the fact that they take themselves seriously. They believe that they’re making real art that speaks to people’s everyday lives. In one scene, Diggler gives an over-the-top, egotistical interview in which he claims that his films improve married couple’s sex lives and thus lead to happier and longer lasting marriages. He sees himself as a civil servant.

But we the audience, from our “enlightened” vantage point, can only see him as a sex worker, engaging in the most base, unsophisticated, primal act possible. We laugh because he’s making porn, and yet is sincere about it. The tragedy that underscores the comedy is that no one outside the porn subculture will take them seriously. Buck Swope, another porn star, can not receive a loan to achieve his dream of opening a stereo-equipment store because of his stigmatized past in porn. Diggler fails to gain the credibility and integrity he desires as a porn actor, and Horner’s career initially suffers because he refuses to use videotape, which he thinks hurts the quality of the film even though it’s a boon for business. The hubris common to the main characters appears to be that they dare to be sincere and care about their work. And we laugh because it’s so antagonistic to what our culture values: cynicism and irony. In a reversal of conventional value systems, these characters, supposedly endemic of an amoral, hedonistic subculture, actually exhibit certain honorable qualities that the mainstream lacks.

Anderson clearly sees himself reflected in these characters, struggling to develop an art form in a world that doesn’t share the same vision. This grappling with artistic identity manifests in distinctly self-referential ways. Anderson has clearly chosen to explore this era, the Golden Age of Porn, because it embodied a development in cinematic forms that he saw as being symbolic of where the medium was heading: pure erotic appeal and escapism that disregarded plot, dialogue, and character development. These evolving mores reflected the ’70s-and-early-’80s consumer culture that demanded these things: Sexual arousal, entertainment over art, and simple instantaneous gratification. In an early scene, when Horner first discovers Diggler, he prophesizes that he will be the star that captures an audience’s attention for the whole plot. Later in the three-hour narrative, Horner refuses to participate in the newest movement in porn, orchestrated by the financiers, to turn to videotape at the cost of the script, and dialogue so that more sex can be funneled out to consumers.

But the film isn’t just about the crisis of the modern artist. It also centers around the average American and a loss of what it means to actually be an American—what we should aspire to and what binds us. Anderson has explored these questions in relation to the American dream throughout his oeuvre, which cannot be understood without them. Diggler fits an archetypal character mold set for a meditation on the American dream: ambitious, middle-class background, seeking to make something of himself. In one reading of the film, Diggler might represent the fallacy of the American dream and its illusory promises, instilling in Americans an all-consuming desire that drives the capitalist machine at the cost of a moral compass. This certainly is the case for Anderson’s “There Will be Blood,” but it seems too cliché for “Boogie Nights,” which replaces industrious, capitalist drive with sex drive. The desire for success and authenticity, which might be associated tangentially with some notion of the American Dream, appears wholly antiquated in the modern world, which opts for sexual stimulation and distraction over artistic innovation.

As Anderson displays in “There Will Be Blood,” the American dream has profound flaws and inherent contradictions. It once gave people a common vision and yet now is something to laugh at—it’s just ironic. That does not mean Anderson calls for a revival of some ideal common vision as obsolete as the American Dream. But the despair, addiction, violence, and pain that Anderson presents certainly reveals that we need to give people something sincere to believe in—something more, at least, than irony and cynicism.

The brilliance of “Boogie Nights” lies in the way that it takes a world that would appear irrelevant, if not antithetical, to political discourse, and draws a causal linkage between the two. How could the “depraved” world of porn, which represents everything that traditional conservatism loathes, actually coalesce into the eventual election of one of the most deeply conservative presidents in American history? Anderson proposes that in a country without cultural or political direction, a slogan that reads “Let’s Make America Great Again,” (the original one), and that fabricates some fictional past that never existed, seems like the best bet. It fills the void. What should scare us is that we keep laughing.

Twenty years later, audiences find “Boogie Nights” and its sincere, honest Dirk Diggler just as naively humorous as they did in 1997, which suggests that we have not yet escaped this milieu of irony. It may not be surprising, then, that when the same campaign slogan came around in 2016, it worked just the same.

Luke Goldstein can be reached at lwgoldstein@wesleyan.edu.