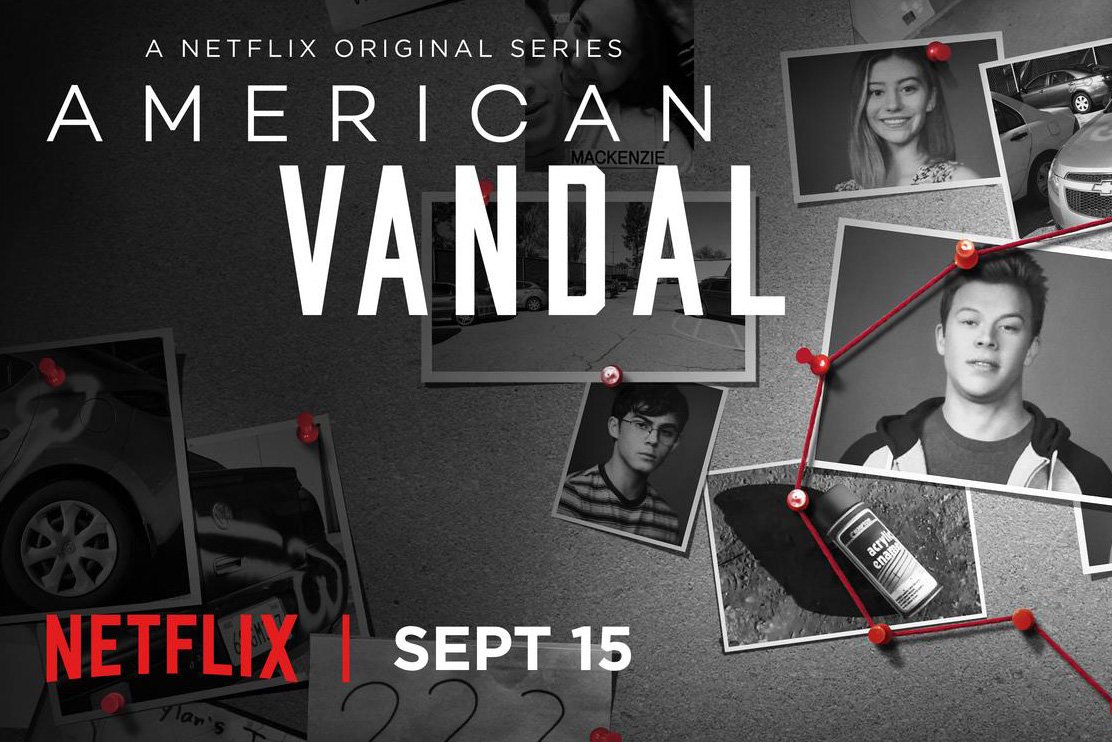

c/o bleedingcool.com

Who drew the dicks?

This is the question behind Netflix and Funny or Die’s newest series “American Vandal,” an eight-part true crime mockumentary that mixes the concepts behind hits like “Serial” and “Making a Murder” with, well, a four-hour dick joke.

The show revolves around Dylan Maxwell, a California high school student accused of spray-painting phallic imagery on 27 of his teachers’ cars. All evidence points to Dylan, whose motive, weak alibi, and propensity for dick drawing make him the perfect suspect. The school board expels him immediately and no one questions it—no one except an aspiring young filmmaker and his best friend, who ask the question no one else will: can we prove beyond a doubt that Dylan is responsible?

It’s an outrageous premise, one of which I was well aware when I sat down to watch it. Even though my sense of humor isn’t exactly what I’d call highbrow—I’m a 20-year-old who thinks fart jokes are way funnier than they should be—I didn’t have the highest of expectations. I figured I’d watch an episode, see how it was, and then go from there.

That, folks, is where “American Vandal” gets you. The show, albeit, based on an undeniably absurd premise, has an incredible capacity to create truly clever comedy out of the stupidest of concepts. It is able to do this, in part, due to its blatant self-awareness, exemplified best when Dylan’s teacher declares: “I’ll never understand what’s so amusing about penises.” Dick jokes are, after all, one of the lowest forms of comedy. You don’t have to be Dave Chappelle to shout, “that’s what she said!” after someone says the word “balls.”

At the same time, some of the best and most ingenious jokes in comedy have been dick jokes, like the now-iconic “Middle Out” scene in “Silicon Valley,” when the characters attempt to calculate the most efficient way to jerk off every audience member at a tech competition. Pulling off jokes like these takes a firm understanding of the power of nuance, and that’s exactly what the writers of “American Vandal” are so good at. One of the most subtle yet hilarious scenes is one in which Peter (the filmmaker), Sam (his right-hand man), and Gabbi (Sam’s friend with a car) try to decipher the meaning of a text conversation between one of the most popular girls at Hanover High and the school board’s key witness, who claims the two got to third base. Their struggle to establish a distinction between “hey” with one y and “heyy” with two ys, the latter of which they decide definitely indicates that someone wants to hook up, is both relatable and hilarious, and it is so successful because it’s simple.

This is the genius of the show. It’s an endless, over-the-top dick joke, but the show is at its funniest when it is simple and bizarrely serious. I got so wrapped up in my theories about the culprit that I didn’t realize I was obsessing over the identity of someone who spray-painted a bunch of dicks on their teachers’ cars.

I also didn’t realize that I was going to spend four straight hours watching this show. That’s the problem: you go in expecting to be turned away by the sophomoric premise, but by the end of the first episode, you’re blown away by the depth, not only of the show’s comedic genius but of its technical genius as well. It has all the captivating aspects of real true crime shows: the overcrowded cork boards, the re-enacted timelines, the gut-wrenching cliffhangers, and the belief of the filmmakers that nothing—not even people’s lives and reputations—more important than uncovering the truth.

The best part, though, is the fact that the show is, as one hilariously on-point critic wrote, about “15 percent longer than it needs to be” because the characters making the documentary continue to insert themselves into the plot, throw around wild accusations, drag their own personal drama into the filmmaking process, and turn the making of their film into the focus of the story instead of the incident that it’s supposed to be about.

The way in which these elements come together is hilarious, compelling, and at times even heartbreaking. In the end, “American Vandal” is so much more than its juvenile premise. It’s a captivating piece of satire with wit, heart, and yes, a lot of dicks.

Erin Hussey can be reached at ehussey@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed