How Matthew Weiner’s Senior Thesis Informs “Mad Men”

“Mad Men” became one of the catalysts in my decision to apply to Wesleyan early decision when I was a senior in high school. I always found the show more critical of the toxic culture it captured than affirmatory, and something about it rendered me more receptive to introspection than any other cinematic experience could. All of this, of course, stems from the frequently marketed fact that the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, graduated from Wesleyan in 1987.

“Mad Men” became one of the catalysts in my decision to apply to Wesleyan early decision when I was a senior in high school. I always found the show more critical of the toxic culture it captured than affirmatory, and something about it rendered me more receptive to introspection than any other cinematic experience could. All of this, of course, stems from the frequently marketed fact that the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, graduated from Wesleyan in 1987.

The Weiner paper trail—from University communication briefs to his more intimate Paris Review interview—deepened my curiosity about the show and its auteur. One striking example is that I applied to the College of Letters, now my major, in part because Weiner majored in it. My pursuit of Weiner’s footsteps mostly ends there, aside from some lazy connections I’ve made between the COL’s broad conception of the Western canon and certain motifs in the show, such as the season 6 opener with Don Draper (John Hamm) reading Dante’s “Inferno” on the beach.

Yet there was one more item that caught my attention one evening—or maybe morning—when I was pulling an all-nighter in the COL Library my junior year. Pondering the subject and scope of my own thesis, I was poring over the wall of black-bound theses from generations of COL alumni when suddenly one stood out: “Vaudeville” by Matthew Hoffman Weiner.

While the intertextuality of “Mad Men” has been the subject of myriad think pieces and TV criticism, Weiner’s thesis and early development as a writer have not been analyzed along with the show thus far.

“Vaudeville,” Weiner’s year-long project with advisor F.D. Reeve—a pillar of the COL department at Wesleyan and the father of actor Christopher Reeve—demonstrates the future writer’s disparate interests and poetic growth over the course of some 40 pages. Allusions in certain poems, such as “Pseudonym,” reveal influential figures like George Orwell and Leo Tolstoy. Settings in the collection range from Utah to Marrakech, ending in New York.

Some poems meet their ambition, while others seem to fall short, particularly in length. Signed in 2013, Weiner wrote a tongue-in-cheek additional acknowledgment in the inside cover.

“To whom it may concern—It may not look like it, but this was a lot of work!”

While much of “Mad Men’s” praise focused on its scrupulous attention to historical details—depicting a period of American history during which Weiner was either an infant or not alive at all, given that he was born in 1965—the broad conception of American culture and the façade of its proverbial dream is very much present in “Vaudeville.”

It may be hard to find an ancestor to Peggy Olson (the springboard role for the flourishing career of Elizabeth Moss, most recently star of “The Handmaid’s Tale”) or a kind of pilot episode in the showrunner’s collection of college poetry, but certain poems lend themselves to a sort of prescience that is striking considering the fact that the show wouldn’t hit the airwaves for another 30 years.

The thesis’ titular poem demonstrates the same sensitivity to performance and attention to rich images that came to define “Mad Men”’s aesthetic, such as bowler hats:

“So was the show-biz of living / distilled in its bigness: / the faces of clowns / the crooner’s bow tie / the dancer’s delicate shoe, / the comedian’s eyes / shielded by a bowler / at the moment of misfortune.”

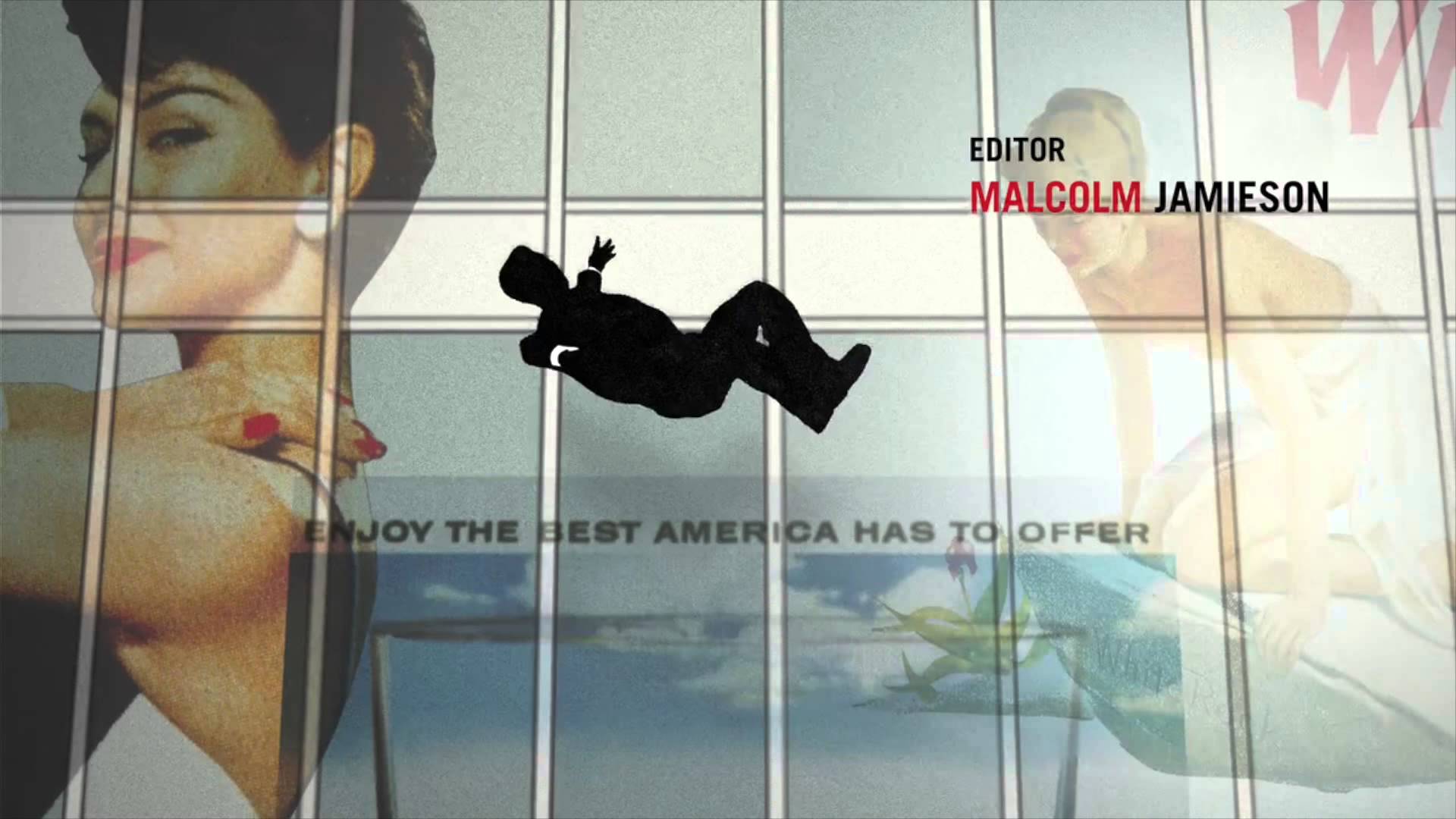

Others, such as “The Tower,” have post-facto allusions to some memorable shots in “Mad Men,” such as the bird’s eye view-plan contre plongée of the scores of working men in hats scurrying around the office turnstile on Madison Avenue. The potential of falling in “The Tower” can also be read as an early version of the famous intro sequence to “Mad Men:”

“The height, four stories up,

revealed a landscape bursting with despair.

I saw just the tops of heads; bald spots,

places where braids spring from,

kerchiefs, headbands, hats.

Personalities read from that high—

Those stable, walking paths

Like water running in a gully;

Those wandering, sniffing the territory,

Digging up the lawn;

Those lost,

Fixed randomly like thumbtacks.

Sitting on the edge dangling a limb,

I was alive with the prospect:

The thrill of dropping a cinderblock, or an anvil,

Or sending an automobile into the landscape,

Compared to my body balanced gently,

Which could sail down like a lame arrow

And organize the crowd in a perfect circle.”

If you hear the violins playing from the opening credits upon reading the last stanza and its morbid implications, you’re not alone.

As the ultimate literary payoff for sticking with the whole thesis, Weiner saves the best for last. If there is any poem in here that can be compared to the totality of his Emmy Award-winning show, it’s “New York Fantasy.” Besides being the most well-rounded poem in the collection, it captures the ethos of the illusion of New York City.

There’s a loss of innocence that happens over the course of the piece, which makes one wonder whose innocence is being lost. Which kind of New Yorker is the narrator? Weiner’s hailing from Baltimore apparently did not preclude him from using a narrator who’s a native to the Big Apple—and pulling it off. Yet part of the beauty of the poem is the ambiguity of the New York experience and who lives it. E.B. White’s legendary tripartite breakdown of New Yorkers still holds true here: “Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness; natives give it solidity and continuity; but the settlers give it passion.”

Weiner’s concluding poem may be about all three, especially the last two stanzas.

“A stranger is dwarfed by

Mountains of iron,

Temples of lead, brick,

Walls of glass pulled

Over the mesh of steel

Like a transparent skin.

In the big city,

I become a building,

Vaulting through the shadows

Of monuments

That break the sunlight

On the pavement,

Constructing myself

With lives,

A container of ghosts.”

As humble as he may have been in his 2013 note, “Vaudeville” is a true sign of the potential Matthew Weiner has demonstrated in his career. It also bodes well for his return to literature in his upcoming novel, “Heather, the Totality” (expected Nov. 2017). If one needs any reassurance that a Wesleyan education can lead to a flourishing professional career, look no further than “Vaudeville” and “Mad Men.”

Jake Lahut can be reached at jlahut@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @JakeLahut.

Achtung, grammar Nazi! Zist typo vill not shtand! Schnell! Schnell!