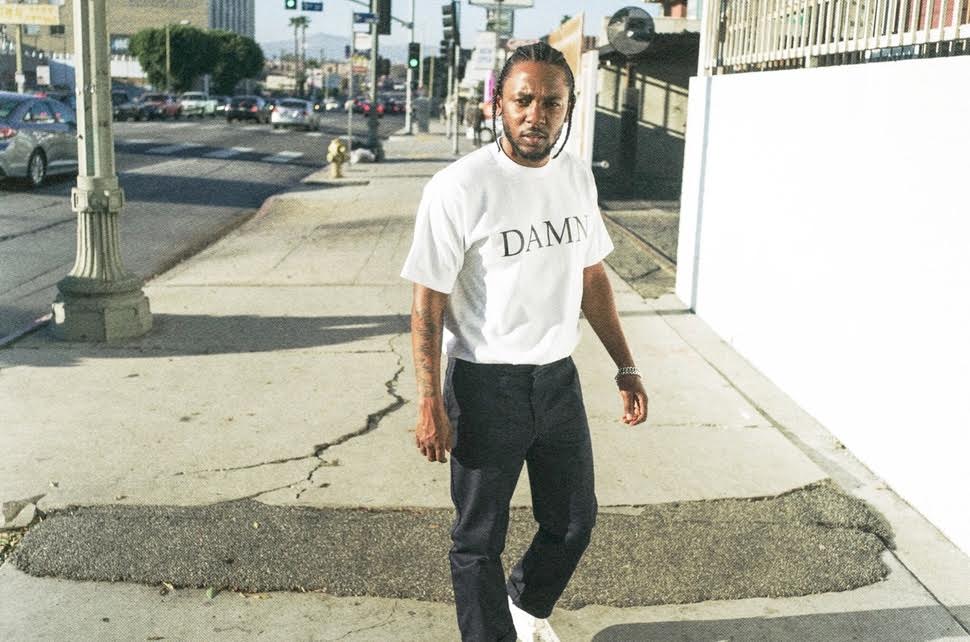

c/o okayplayer.com

This past March, when questioned about his current preoccupations, Kendrick Lamar replied simply, “Family.” On his new album DAMN., gone is the fixation with the widespread effects of the American music industry and the U.S. political system at large that marked his ground-breaking 2015 LP To Pimp a Butterfly. In its place are intense ruminations on Lamar’s personal emotional struggles that explore what it means to be an uncle, a cousin, a Christian, a resident of Compton, and—of course—the greatest rapper alive.

In the first seconds of DAMN.’s introductory song, “BLOOD.,” Kendrick reveals the guiding question of the album when vocalist and producer Bēkon ponders, “Is it wickedness? Is it weakness? You decide,” pulling the polarized emotions of strength and weakness, pride and humility, and love and lust into an album throughout which these themes are littered. Implicit in this dichotomy of emotions is the polarized nature of Lamar’s life as a self-proclaimed “hip-hop rhyme savior” who nonetheless struggles with self-esteem, self-doubt, and fear in a state that brutalizes Black and Brown bodies every day.

It’s not difficult to see the manifestations of this bipolarity in the sequencing of DAMN.’s tracks, as the assertive, thumping “DNA.” is followed by the contemplative, mellow “YAH.” and the introspective, self-loathing “PRIDE.” is succeeded by the album’s brash, boastful lead single, “HUMBLE.” Perhaps the most severe, and ultimately disappointing, of these two-song conflicts is the pairing of the haunting internal monologue “LUST.,” which contemplates the fragility of Black life mainly in the revisited lyric of “Whatever you doin’, just make it count,” with pop song “LOVE.,” which is perhaps the most compromised Kendrick has sounded on a song since his major-label debut in 2012. This pattern of emotional divergence is even further explored in the two-part “XXX.,” where Kendrick parodies the dichotomous nature of his personality, rapping, “If somebody kill my son, that mean somebody gettin’ killed,” just a few lines before heading to a convention to say, “Alright, kids, we’re gonna talk about gun control.” Mirroring the change in lyrical tone is the song’s beat, which swaps blaring sirens and exacting percussion for a piano loop and a hook by none other than Bono. To those saying Kendrick has scrapped his jazz influences in favor of hard-hitting trap beats, I would advise looking past the direct, shamelessly repetitive piano of “HUMBLE.” and the deafening drums and ad-libs of “DNA” to the smooth guitar of The Internet’s Steve Lacy on “PRIDE.” or the beautiful flip of The 24-Carat Black’s “Poverty’s Paradise” on “FEAR.”

Although this perpetual theme of emotional opposition can easily be applied to divisive issues of gang violence, or even partisan gridlock, especially on “XXX.,” which laments that “It’s murder on my street, your street, back streets, Wall Street,” Kendrick mainly sticks to his promise of reflection on community, family, and, most viscerally, the self. As the tape continues, the listener can see that the title evokes not just the eternal “Friday” clip but also a deep contemplation of damnation. Indeed, even the title suggests the two-sidedness of Kendrick’s emotions, as the phrase can be interpreted both as an aggressive, explicit self-affirmation and an evocation of God-given suffering and misfortune.

DAMN. contemplates what it means to be part of “a cursed people,” doomed to be blind to each other’s sufferings, as Kendrick’s cousin Carl explains at the beginning of the sprawling, emotional climax of the album, “FEAR.” Venturing from the emotional and physical abuse Kendrick was threatened with as a child and the daily premonitions of death he can’t help but contemplate to his fear of divine vengeance, lost riches, and absent creativity, “FEAR.” epitomizes the paranoid state of mind of a 29-year-old hip-hop legend who feels lucky to have made it past 17. Kendrick’s stray premonitions of death, ranging from guesses that he’ll “prolly die because these colors are standin’ out” or “prolly die from one of these bats and blue badges / body slammed on black and white paint, my bones snappin” or “maybe die from panic or die from bein’ too lax,” reflect a learned paranoia akin to his fallen idol Tupac Shakur, who was known for his frantic suspicion of others and obsessive fear of death. On “FEEL.,” Kendrick again channels Pac’s self-imposed seclusion and distrust of others, expressing his disillusionment with an outside world where no one is praying for him.

Just as Pac reacted to his coinciding fame in hip-hop culture and vilification in the media by choosing to isolate himself and speak out vehemently against other rappers, Kendrick has chosen to call out his foes and assert his superiority in response to his last album’s deification and subsequent condemnation by Fox News talking heads. After sampling Fox News host Geraldo Rivera’s absurd, apologetic comments regarding the “damage” hip-hop has done to Black communities, Kendrick retorts, “You mothafuckas can’t tell me nothin’ / I’d rather die than to listen to you” on the album’s first full track, “DNA.” Kendrick’s snide, brief response to Rivera and Fox News at large signals his disinterest in even entertaining the views and opinions of others regarding his art. In many ways, his response that “I’d rather die than to listen to you,” indicates that songs like “HUMBLE.” and the previously released “The Heart Part 4” are not so much diss tracks pointed at Drake, Big Sean, or anyone else, as songs of irritation and isolation that are meant to illustrate Kendrick’s absolute authority over his critics. Kendrick won’t even give half a bar to diss any rapper, as Jay-Z did to all the “other cats throwing shots at Jigga” on Nas’ diss track “Takeover.”

No, as one should already know, Kendrick Lamar’s greatest opponents are none other than himself, or “America’s reflections of me” as he puts it on “XXX.” However disconcerting and divergent Kendrick’s emotions are on DAMN., he finds reconciliation in knowing that his own demons are his worst enemy. On concluding track “DUCKWORTH.,” with this newfound recognition in mind, Kendrick discards his fears of divine damnation, saying God’s “a true comedian, you gotta love him, you gotta trust him” before reflecting on the fortuity of his own existence and success, all based on a chance encounter between his label’s president, Anthony, and Kendrick’s own father, Ducky. As Bēkon sings prophetically on the very same track: “It was always me versus the world / until I found out it was me versus me.”