Forbidden love and ruminations over what makes life worth living are fine subjects for cinema, and they could have been enough on their own to make “Frantz” a perfectly pleasurable film. The film goes beyond them, however, to intersect the heavy existential subjects with the toll of war. This type of engagement has become more foreign Western society in the 21st century, particularly for the American viewer, who will have the chance to see the Franco-German film in limited release.

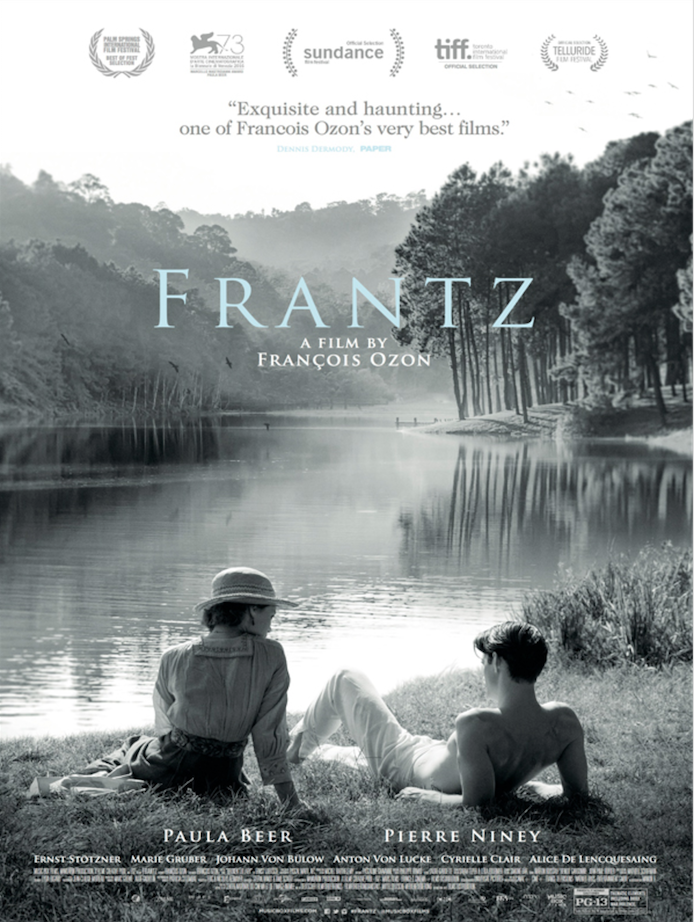

Making a rare stateside appearance at the Madison Art Cinema on Friday, March 24, “Frantz” carries with it a résumé saturated with awards and nominations, featuring 11 Nominations—including one for Best Film—at the 42nd César Awards, which are the French equivalent of the Oscars. Lead actress Paula Beer won the Marcello Mastroianni award for Best Young Actress, and the film has been an official selection at the Sundance, Venice, Palm Springs, and Lincoln Center film festivals.

Set in post-World War I Germany, the film follows Anna (Beer), whose partner was killed in the war, in her quest to find a life worth living amid the horror and despair of a broken and defeated nation. Her late fiancé, the film’s titular character, only appears in flashbacks and dreams, played in silence by Anton von Lucke. Anna lives with Frantz’s parents, the Hoffmeisters, who continue grieving for their son by keeping his room as he left it and by guarding his violin out of hope that he will someday return to play it. One day, Anna witnesses a lean and well-quaffed Frenchman, Adrien Rivoire, lay roses at the grave of her dead love.

Rivoire is played by Pierre Niney, who rose to fame in France after his portrayal of Yves Saint Laurent in a biopic that won him the César for Best Actor. Niney also garnered critical acclaim for his role in “Un Homme Idéal (A Perfect Man),” where he plays a fraudulent writer who builds an A-list career by using the diary of a forgotten soldier in the War of Algerian Independence. Niney’s slender features and praying mantis-like eyes lend him to a broad range of emotional legibility, as well as an impeccable resemblance to Mesut Özil, a European footballer whom Niney may very well play in yet another César-winning biopic.

Under the direction of François Ozon, Niney and Beer share impeccable chemistry on the screen, building tension through the forbidden love between a French soldier and a German mourner. A tension that suddenly twists when it is revealed that Adrien killed Anna’s fiancé and that his trip to her hometown is to ask for forgiveness over fulfilling his wartime duty rather than to pay his respects to Frantz’s family, who he had conned into believing that he was one of Frantz’s friends from his time studying in Paris.

While the structure of the first half of the film appears to set up and subsequently execute upon basic tensions with foreshadowing, all bets are off after the reveal that Adrien killed Frantz. However predictable the plot twist may feel, Ozon is liberated thereafter to give a nuanced and cutting portrayal of the hopelessness and anguish of post-war Europe. The lucky citizens who remain carry the weight of the dead upon their shoulders as they confront the same difficulties of the human experience aside from the war.

The transitory nature of the film’s formal qualities makes for a surprisingly emotionally wrenching experience. Frantz’s father, Doktor Hans Hoffmeister (played in quintessential gruff by Ernst Stötzner), goes from veering towards fascism following the death of his son (“every Frenchman is my son’s murderer”) to embracing Adrien as the rightful heir to Frantz. The film’s color palette transitions from black and white to color at a few key points, which could have failed miserably if not for Ozon’s delicate touch and equilibrated cinematography. Train rides and brisk walks through museum corridors become symbols for the passing of time and the forgiveness of the sins of war.

Just when it seems that Anna and Adrien can finally be together after she forgives him for killing her fiancé, it is revealed that Adrien has found himself a girlfriend to live with him in his mother’s chateau outside of Paris. A hopeless Anna hastily packs and heads back to the train station, escorted by Adrien for what could be the last time they see each other. The relief ending does not come in the kiss on the platform and spur decision to hop onboard the train, but rather in the halls of the Louvre, where Anna stares at Manet’s controversial painting “Suicide.”

As University Professor of Letters and Diaspora founder Khachig Tölölyan says, “The story of the first half of the 20th century is that of Europe slowly committing suicide with World War I and World War II.” A palpable sense of nihilism pervades the film’s attempt to capture the essence of the era, leading Anna to perpetuate a comforting lie started by Adrien.

Yet in his falsehood, there emerges a truth. Adrien first fibs about Frantz by saying that they both loved a Manet painting in the Louvre with “a pale white boy with his head turned back,” which ends up being the cadaver figure of Manet’s “Suicide.” The painting starts as a Freudian slip for Adrien—who, before becoming a sort of muse and spiritual rock for Anna, finds no purpose to live other than to beg forgiveness from the man he killed. By the end, the Frenchman is left with an almost Sartrian form of radical freedom. Out of the trauma of war and the deceit that attempts to cover it up like a make-shift bandage, Anna discovers that an honest confrontation with the horrors of life and a liberation from imperfect loves serves her better than maintaining a rosy façade, at least in the halls of the old masters.

2 Comments

增达网QQ-17148153

感觉不错哦,认真拜读咯!

QQ717459716

富强、民主、文明、和谐,自由、平等、公正、法治, 爱国、敬业、诚信、友善。