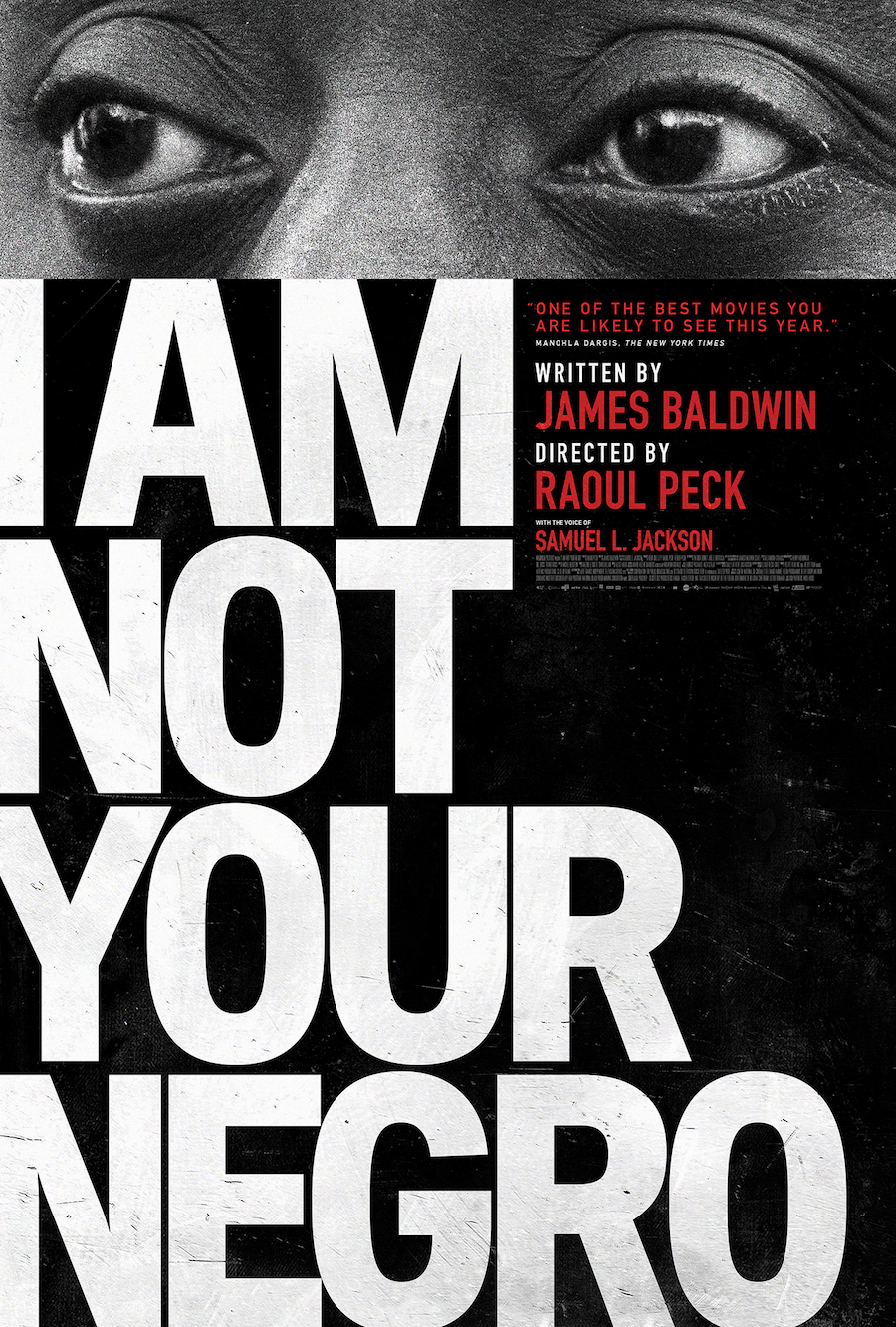

c/o indiewire.com

Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro” paints a portrait of James Baldwin’s life in the 1960s while offering audience members a glimpse into American race relations during one of its most tense and revolutionary moments. The documentary takes Baldwin’s own voice and uses it as its transcript, deriving most of its narration from his unfinished manuscript for “Remember This House,” a book that provides an account of the deaths of his friends and fellow Black activists Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. Since Baldwin had only written 30 pages of the book before his death in 1987, the narrative compass of the movie also draws from live interviews and essays that the writer completed throughout his life.

Though “I Am Not Your Negro” has been marketed as a documentary centered on the life of James Baldwin, the main character in the film is perhaps, more accurately, race in America. Throughout the movie, we see montages of headlines and media footage from the mid-20th century: a clip showing 15-year-old Dorothy Counts facing a violent white mob while desegregating a white high school in Charlotte, NC; numerous advertisements from the ’60s showing Black Americans as willing cheerful servants; a white power rally where a Black woman is shown being literally bludgeoned to death.

These moments in the film are products of a bygone era only in appearance. Grainy black and white footage makes for unfocused shots of anti-Black violence being carried out by law enforcement personnel and laypeople alike. White protesters carry picket signs that display messages that are unthinkable today. There are swastikas, efforts to equate racial integration with communism, children hailing white power.

The meaning of history changes when these clips are shown beside photos of Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice—before news footage from the streets of Ferguson. For those who feel that the current political climate is one that has focused too much on race, as if it is unique to our time, it becomes undeniable that race, culture, and power have forever been intertwined in our nation’s history. Treating race as something we’re only now seeing, or should stop seeing, contributes to the erasure of the struggle, progress, and activism both then and now.

“Black history is American history,” reads Samuel L. Jackson as the voice of Baldwin, in what is perhaps one of the most poignant lines in his narration. People of color—and especially Black Americans—have long been pushed to the margins politically, socially, and artistically. The film, while exploring Baldwin’s own experiences as a Black writer, also engages with subject matter of Black people in the arts, especially within cinema.

“I Am Not Your Negro” also includes footage from the 1958 movie “The Defiant Ones.” In one scene, a pair of convicts—one Black and the other white—escape prison. In an ever-climactic moment, the white man falls off the train and, surely enough, his companion jumps off voluntarily to continue their journey in solidarity. Baldwin, in both jest and seriousness, commented that while white liberals found relief in the moment, most Black audience members were yelling, “Get back on that train, you fool!” The scene, like many others in American film at the time, is still emblematic of the media’s attempt to appease white guilt. By jumping off the train, the film posited the men as brothers bound by mutual forgiveness, regardless of their race—a differentiator that would have made their two lives almost incomparable.

If Black history is American history, American history is far from pretty—and far from the idealized melting pot narrative we tell our children. It is certainly not the “home of the free,” but is the “land of the brave,” says Baldwin.

“Violence is as American as cherry pie,” he writes, quoting Black activist H. Rap Brown and going on to proclaim that we must stop treating violence as a phenomenon endemic to communities of color. “I Am Not Your Negro” aims to advance this message, to unveil the normalized violence brought forth by police during the civil rights era up until this very day. It is only with awareness of American history—the untold American history—that we can move forward and approach the envisioned America that is written in the textbooks. Until then, social progress will be stunted because we don’t acknowledge and learn from the most comprehensive account of our history—the one that takes into account the plight of marginalized people upon whose backs our country was built.

As for Baldwin’s personal life, we learn about his sense of duty and his reluctance to attach himself to larger causes like the NAACP, the Black Panther Party, or even the Church. After spending a decade abroad in Paris, he chose to return to the U.S. because he felt a personal need to engage in Black activism on the ground. However, he appeared to feel stifled by lack of a larger group identity. Baldwin mentioned a white teacher he had as a child, and how she took a special interest in him by showing him books and plays, along with attention. He didn’t want to join the Panthers because of the positive effects that certain white individuals had added to his life. For that reason, he was usually depicted as a sort of lone figure in the spotlight—advocating for those around him, but doing so on his own.

Race being the central focus of the film, the narrative does not include any exploration into Baldwin’s sexuality. As a queer Black writer, Baldwin’s sexuality is only made relevant in the film at the most perfunctory level, when FBI records show that he was deemed a person of interest for his prominence as a writer alongside his purported sexual deviance.

Considering that the film delves into great lengths to explain the importance of acknowledging history, politics, race, and culture at an intersectional level, it was jarring that such a point of public contention within Baldwin’s identity was so glossed over. The question that remains at the film’s conclusion is how Baldwin’s identity as a queer Black artist affects the Black American experience: How did these separate components of his identity work with and against one another in relation to his activism? How has that changed for queer people of color today?

“I Am Not Your Negro” raises many poignant questions about race and politics in America, focusing in on the life of a tremendously important voice and out into the broader scope of race relations in the country over the course of the mid-20th century. The film reminds audiences that though it is a documentary deeply rooted in the past, the narrative conveyed within it continues to unfold with each new day in America. We must move forward, but first, we must turn to history.