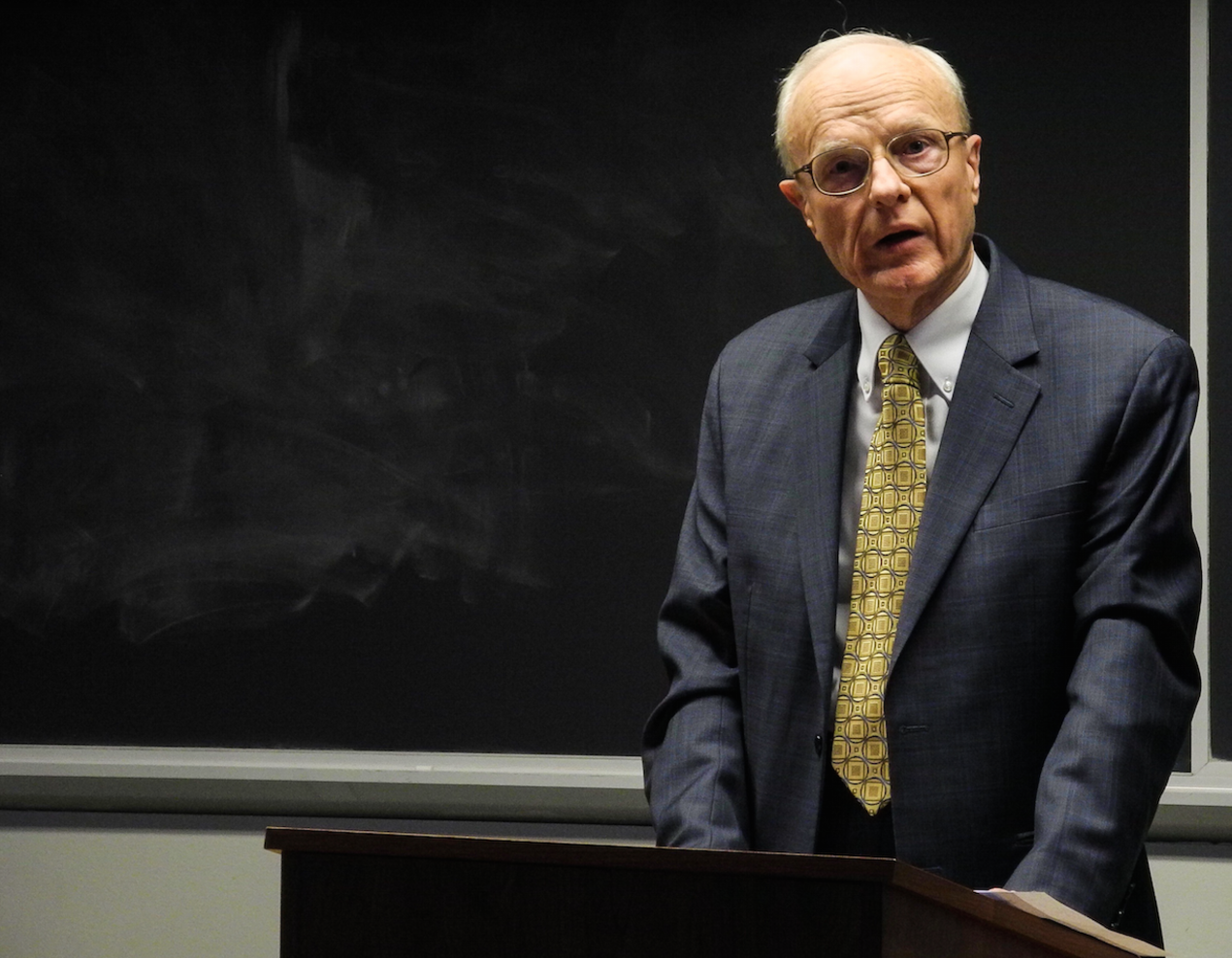

Intellectual historian George Nash will be the first to tell you that the Democratic Party won the first half of the 20th century. But over the past fifty years, conservatism has reached an ascendant position in American politics. What is its greatest achievement? As Nash argued at the University on Wednesday, Feb. 22, it be might validating itself as an intellectual tradition in the first place.

The author of “The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945,” which has been updated periodically since it was published in 1975, Nash has been referred to by academics and public intellectuals of all stripes as the “court historian” of the conservative movement. Historian Jennifer Burns wrote that the book is “literally the first and last word on the topic.” While Nash has been lauded for the depth and rigor of his historical analysis, his greatest achievement in the book may be bringing coherence to a movement often at war with itself as much as the progressive milieu.

“Conservatism has not and never has been monolithic,” said Nash. “It has many points of origins, and its diverse tendencies are not always easy to reconcile.”

Henry Merritt Wriston Chair in Public Policy Marc Eisner offered some opening remarks. He recalled the last time Nash lectured at the University – almost ten years ago – on the topic of neoconservatism in the post-Cold War era. The irony of our distinctly different historical moment was not lost on Dean Eisner.

“Oh how things have changed,” Eisner laughed.

During his lecture, Nash was primarily concerned with tracing the disparate and often conflicting strands of modern conservatism that emerged during the era of post-WWII prosperity. While his talk was titled “American Conservatism and the Problem of Populism (and Where Does Trump Fit In?),” he primarily focused on characterizing the three ideological factions that emerged to challenge progressive control of government and society in the 1950s and 60s.

Classical liberals extolled the virtues of the free market. Economists and social theorists such as Friedrich Hayek, Thomas Sowell, and Milton Freidman worried that post-New Deal America was drifting down what Hayek dubbed “The Road to Serfdom,” towards a highly bureaucratized and centrally planned tyrannical state. Next were the traditionalists, who stood aghast at mass society in the U.S. and its totalitarian corollary in the Soviet Union. Writers like Russell Kirk advocated for a return to religious teachings, the virtues of natural law and community institutions that reinforced social cohesion and moderated the influence of government. Finally, there were the anti-Communists, who Nash described as “militantly evangelical” in their hatred of Soviet collectivism. The group included former Communists such as Whittaker Chambers, and were especially effectively in leveling an intellectual challenge against the practices of Stalinism.

The edifice of what would become The Right of the 1980s needed a leader able to consolidate these distinctive visions, and they found their man in William F. Buckley and his magazine The National Review. The Review was founded in 1955, with the goal of “stand[ing] athwart history, yelling Stop.” Buckley and the magazine personified each impulse in the fledgling conservative tradition: Catholic conservatism, staunch anti-Communism, and a defense of the free market. Nash argued that it was anti-Communism in particular that was most valuable in the effort to unite these sects, centering the movement in opposition to a great external enemy, the U.S.S.R, the nemesis of the political, economic, and religious freedom modern conservatives treasured.

On the presidential level, conservatism would find its first true champion in the 1981 election of Ronald Reagan. The Reagan Revolution of the 80s signaled the rise of social conservatives, incensed by Roe v. Wade, and a mutation of the anti-Communists: Irving Kristol’s neoconservatives. The neocons, “liberals mugged by reality,” as Kristol once quipped, were mainly comprised of former Democrats who fled the party after being disillusioned with its foreign policy objectives. By defecting from and critiquing the Left, they were able to attack the notion that only progressivism could possess intellectual merit.

“Reagan was able to do what Buckley did a generation before,” Nash said. “They were commanding, ecumenical figures that gave all parties involved the sense they were part of a movement.”

In the 21st century, the downfall of Communism and the absence of a grand foe has intensified the factional strains that have always laid beneath the surface of the movement that Buckley and Reagan consolidated. But no one, including Nash himself, was able to anticipate the rise of a Donald J. Trump and the so-called “alt right,” a movement that has conservative intellectuals at places like The National Review questioning whether there is room for the populist surge in the Right’s tent. As Nash proves, the intellectual history of the GOP demonstrates that President Trump is not treading in conservatism’s uncharted waters. Nash says he suspected that right wing and left wing populism would face off at some point, but he admitted that he never could have predicted the volcanic eruption of a kind of populism in the tradition of “America First” paleoconservatives like Pat Buchannan, the “rough rhetoric” of George Wallace, and the Tea Party protests of 2009.

“I believe we are witnessing something we have never seen in the U.S., an inchoate nationalist populist party that combines right-wing and left-wing elements similar to movements in France and other European countries,” Nash said. “Responding to economic stagnation and the threat of global terrorism, Trumpism and its European analogs are also driven by the notion that ‘elites’ as a whole do not want to or cannot make things better.”

Nash noted that the issue of immigration was a central conceit that ties together many of the tenets of Trumpism.

In a dislocating political environment marked by intense animosity, Nash believes that the central schism of our time is not between the Left and Right, but from those above against those below. He offered several lens through which one might understand the growth of this populist surge, including accelerated cultural pluralism and the influence of social media and mass communication, which has diminished the potential for elite control of public opinion.

In a world where InfoWars and Brietbart News receive press passes in the White House, the power that the National Review’s and Commentary’s of the world have on conservative public policy is in peril. While Nash believes the Republican Party is strong, even as the conservatism of the National Review variety is under threat from Trumpism, he claimed that part of Trump’s electoral success is indebted to two conservative positions that the President embraced: the repeal of the Affordable Care Act and his promise to appoint conservative jurists. These positions give “normal conservatives” in Congress the incentive to collaborate with the President.

Who will win the conservative civil war? While the buck of conservative history may stop at Nash, he offered no specific prognosis for how he thinks this latest lurch in conservatism will play out in the future. Instead, he emphasized two features of conservatism, its ideological flexibility and potential for reimagination, that he believes will allow it to endure. Its future manifestations may be best personified by the quote Nash left his audience with.

“These are our principles, if you don’t like them, we have others,” he said.

Leave a Reply